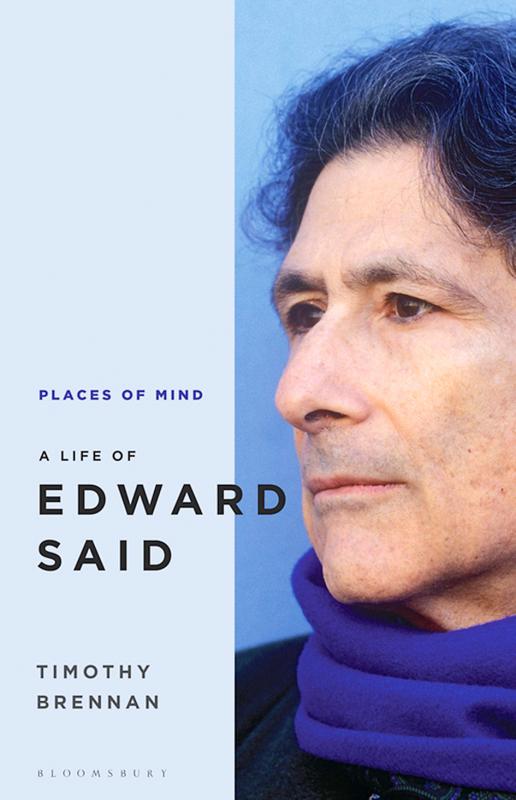

“Long after his death in 2003, Edward Said remains a partner in many imaginary conversations.”

The opening line of Tim Brennan’s biography of Said is true — it’s hard to come up with another thinker who remains so present in his absence. Some 50 or so books have been written about him. His writings are taught in universities across the world. Look on social media and you’ll find him constantly referred to, in easy, familiar terms, by the young across the globe. His portrait is on the walls of the old cities of Palestine, in the company of the martyrs. The events of the past years, not least the Arab uprisings and the counter-revolutionary triumphs that followed them, have been for many of us occasions where we turned to his ideas and his example.

Said bestrode not just one world, but several. Just as he was at the same moment a New Yorker and a Palestinian brought up in Egypt, he was also a literary critic, a theorist, a political activist, a musician and more. And if this led to him being “not quite right” in any one world, his genius was to transmute this condition into the engine of ideas around which a considerable part of the intellectual and political life of these worlds came to revolve.

Brennan was Said’s student and friend, familiar with his ideas and comfortable in his company. For Places of Mind he worked closely with Said’s family, conducted interviews with a wide range of his friends and colleagues and (he must have) thoroughly mined the archive held in Columbia University, where Said taught for his entire career. (One delightful moment in the book is when Brennan finds that Said’s teaching notes from 1964 to 1984 prove his old teacher’s statement that some of his best ideas came from his teaching.)

Nobody is just one thing, Said insisted. Brennan’s achievement is to do justice to the many things Said was and to articulate the synapses that connected his different worlds, so ideas that had their birth in one found their use in another. He has provided us with what you might call a manual of Said; a map of his thoughts and his positions, which, change as they did, could always be traced to a core set of ideas and drives and to do this without ever blunting Said’s subtlety or smudging the clarity of his ideas.

How he attracted a global following and confounded his enemies while busting the humanities out of academia, making literary criticism fashionable, turning the Palestinian image around and defining how we now interrogate history would be impossible to comprehend without some sense of the personal qualities he brought to the table. The small tasters Brennan provides of Said’s throwaway humor, savage sarcasm, loyalty, touchiness, warmth and resilience are signature qualities of the friend I treasured. They are a pleasure to come across. Brennan’s account of Said’s historic Mesa (Middle East Studies Association) debate with Bernard Lewis in 1986 had me clicking on YouTube. I watched in full, relishing again the wit, the glamor, the street cred — the star quality that Said brought to the podium.

In the final paragraph of his memoir, Out of Place (written in counterpoint to his battle with leukaemia, a struggle where he managed to hold the advantage for nine years), Said proposes this summing up of himself: “I occasionally experience myself as a cluster of flowing currents. I prefer this to the idea of a solid self, the identity to which so many attach so much significance. These currents… at their best… require no reconciling, no harmonizing. They… may be out of place, but at least they are always in motion… A form of freedom, I’d like to think, even if I am far from being totally convinced that it is.”

Out of Place is, of course, the inescapable foil against which the first 100 or so pages of Places of Mind will be read — and found wanting. Said’s memoir is a forensic excavation of his young self and the circumstances that led to that permanent condition of “outsider.” He was pretty severe with that young self, so it feels somewhat de trop to have someone else piling in on it. I wonder, though, if Brennan’s harshness with the younger Edward was out of impatience to be once again in the company of the Said he knew — and loved.

“Over three unpromising decades,” Brennan writes, “Said kept the critical spirit alive… and gave it its warmest, kindest, angriest and most honest shape.”

This, he suggests is part of what will keep literary and social criticism alive and relevant. This critical, generous and heartfelt biography will be a serious ally in the enterprise. The conversations continue.

Last week the story of the giant illegal crater dug in Kaohsiung’s Meinong District (美濃) emerged into the public consciousness. The site was used for sand and gravel extraction, and then filled with construction waste. Locals referred to it sardonically as the “Meinong Grand Canyon,” according to media reports, because it was 2 hectares in length and 10 meters deep. The land involved included both state-owned and local farm land. Local media said that the site had generated NT$300 million in profits, against fines of a few million and the loss of some excavators. OFFICIAL CORRUPTION? The site had been seized

Next week, candidates will officially register to run for chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). By the end of Friday, we will know who has registered for the Oct. 18 election. The number of declared candidates has been fluctuating daily. Some candidates registering may be disqualified, so the final list may be in flux for weeks. The list of likely candidates ranges from deep blue to deeper blue to deepest blue, bordering on red (pro-Chinese Communist Party, CCP). Unless current Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) can be convinced to run for re-election, the party looks likely to shift towards more hardline

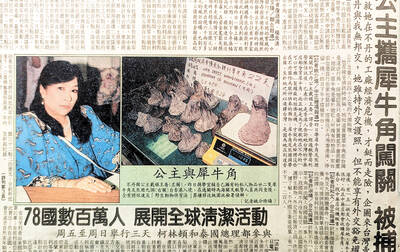

Sept. 15 to Sept. 21 A Bhutanese princess caught at Taoyuan Airport with 22 rhino horns — worth about NT$31 million today — might have been just another curious front-page story. But the Sept. 17, 1993 incident came at a sensitive moment. Taiwan, dubbed “Die-wan” by the British conservationist group Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), was under international fire for being a major hub for rhino horn. Just 10 days earlier, US secretary of the interior Bruce Babbitt had recommended sanctions against Taiwan for its “failure to end its participation in rhinoceros horn trade.” Even though Taiwan had restricted imports since 1985 and enacted

Enter the Dragon 13 will bring Taiwan’s first taste of Dirty Boxing Sunday at Taipei Gymnasium, one highlight of a mixed-rules card blending new formats with traditional MMA. The undercard starts at 10:30am, with the main card beginning at 4pm. Tickets are NT$1,200. Dirty Boxing is a US-born ruleset popularized by fighters Mike Perry and Jon Jones as an alternative to boxing. The format has gained traction overseas, with its inaugural championship streamed free to millions on YouTube, Facebook and Instagram. Taiwan’s version allows punches and elbows with clinch striking, but bans kicks, knees and takedowns. The rules are stricter than the