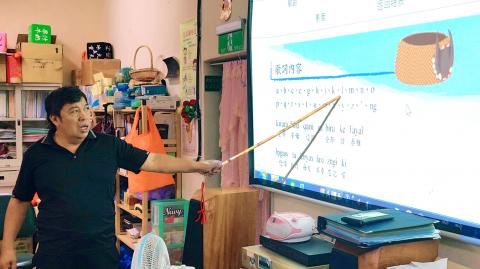

Although Cilaw is fluent in Atayal, she still attends language classes. For most of her life she has used the Zhuyin Fuhao (注音符號) phonetic system to write her native Aboriginal tongue. The septuagenarian now faces the daunting challenge of learning the Latin alphabet.

The language has been marginalized and suppressed by colonizers for centuries. It is seldom heard anymore in her village of Kayu in New Taipei City’s Wulai District (烏來). While missionaries began using the Latin alphabet to write down Aboriginal languages after World War II, the ruling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) banned the practice in 1957 in their push to eradicate all languages in Taiwan besides Mandarin.

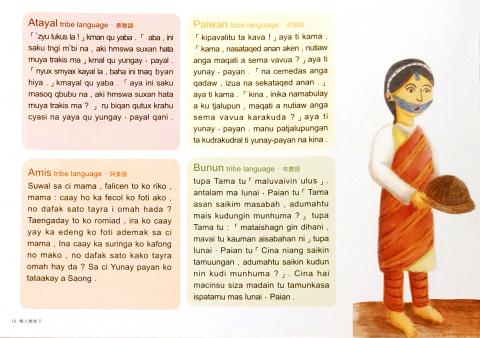

Although the government reversed the ban in the 1980s, romanization of Aboriginal languages was not standardized until 2005. Yukan Batu, a retired principal and tireless indigenous language educator, has a hectic schedule during the school year due to the scarcity of teachers, but during the summer he’s teaching the elderly residents of his home village how to read the alphabet. He’s also created an Atayal lesson book and a set of six children’s books featuring Atayal legends in English, Mandarin, Atayal, Amis, Bunun and Paiwan.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

“Some of my students here speak better Atayal than I do,” Yukan says. “So I thought I should teach them the alphabet. I realized that it’s just as important to teach the elderly as it is to teach the children. If they learn the same system, it will be easier for them to teach the younger people who aren’t as proficient as speakers.”

For example, Cilaw says that now that her grandchildren are taking Atayal classes at school, they’ll come home and ask her questions about their schoolwork, making it practical for her to learn the romanization system.

Yukan considers himself lucky. Since Kayu is the closest Atayal village to Taipei, the language eroded faster than other more remote villages in the mountains. The 63-year-old was raised by his grandmother, who not only spoke to him exclusively in Atayal, but also passed on to him all sorts of legends and histories of their people.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

By contrast, one of his students of about the same age, Lin Chun-mei (林春美), doesn’t have an Aboriginal name and barely spoke Atayal growing up, although she can understand most of it. She hopes to refresh her knowledge out of personal interest and also to teach her grandchildren.

“It is so difficult to learn a new writing system at this age, but I will try my best,” she says.

Although children now learn the language in school, Yukan says one hour per week isn’t enough if they don’t use it at home. Ironically, he says there’s more demand for his services in urban areas, because Aboriginal parents living in cities are worried about their children’s lack of exposure of their traditional culture away from the villages.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

“Since they don’t have access to the culture, they’ll take advantage of what opportunities they have,” Yukan says. “In the villages, they don’t seem to be so proactive since they feel that it’s still around them.”

The key is to foster an environment where the whole village is interested in speaking the language. If old people don’t even use the language, young people have no example to follow, Yukan says. The classes also keep the elderly invested in their mother tongue when most of the village regularly speaks Mandarin or Hoklo (also known as Taiwanese).

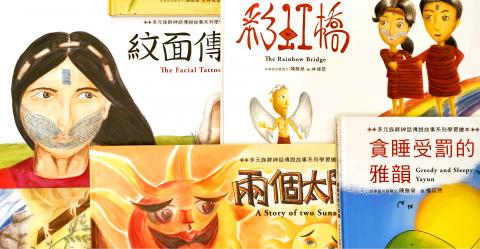

About three years ago, Yukan created six colorful storybooks featuring Atayal legends for children, including A Story of Two Suns (兩個太陽), The Magical Wood Thrushes (靈鳥希利克) and The Rainbow Bridge (彩虹橋). All books include a sample language lesson plan.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Yukan says that although the stories are Atayal, he made sure that other Aboriginal languages are included to reflect Taiwan’s linguistic diversity and to facilitate cultural sharing between different indigenous groups.

“Most Atayal people have heard of these legends as children, but we also need to help preserve them,” he says.

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.

This month the government ordered a one-year block of Xiaohongshu (小紅書) or Rednote, a Chinese social media platform with more than 3 million users in Taiwan. The government pointed to widespread fraud activity on the platform, along with cybersecurity failures. Officials said that they had reached out to the company and asked it to change. However, they received no response. The pro-China parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), immediately swung into action, denouncing the ban as an attack on free speech. This “free speech” claim was then echoed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC),

Many people in Taiwan first learned about universal basic income (UBI) — the idea that the government should provide regular, no-strings-attached payments to each citizen — in 2019. While seeking the Democratic nomination for the 2020 US presidential election, Andrew Yang, a politician of Taiwanese descent, said that, if elected, he’d institute a UBI of US$1,000 per month to “get the economic boot off of people’s throats, allowing them to lift their heads up, breathe, and get excited for the future.” His campaign petered out, but the concept of UBI hasn’t gone away. Throughout the industrialized world, there are fears that

Like much in the world today, theater has experienced major disruptions over the six years since COVID-19. The pandemic, the war in Ukraine and social media have created a new normal of geopolitical and information uncertainty, and the performing arts are not immune to these effects. “Ten years ago people wanted to come to the theater to engage with important issues, but now the Internet allows them to engage with those issues powerfully and immediately,” said Faith Tan, programming director of the Esplanade in Singapore, speaking last week in Japan. “One reaction to unpredictability has been a renewed emphasis on