July 31 to Aug. 6

To the Qing Empire, they were fan (番), or barbarians. The Japanese called them the Takasago, or high mountain people. And the Chinese Nationalist Party referred to them as shanbao (山胞), or mountain compatriots.

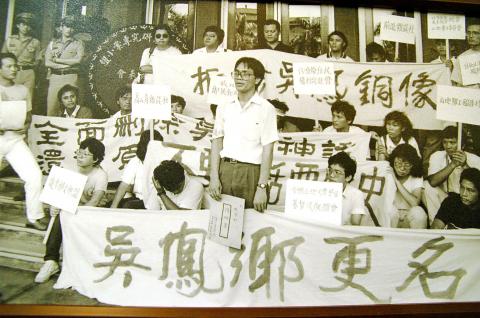

In late 1984, the Aborigines of Taiwan decided that they would no longer bear the designation handed to them by the colonizers. On Dec. 29, a group of 23 Aboriginal and Han Chinese intellectuals got together and formed the Taiwan Aboriginal Rights Association (台灣原住民權利促進會), with one of their demands being that the government officially call them yuanzhumin (原住民, or original inhabitants), which is the term used today.

Photo courtesy of Hsieh San-tai

“The organization was the first one that included the term ‘Aborigine’ in its name,” writes Icyang Parod in the book, Compilation of Historical Material on Taiwan’s Aboriginal Movement (臺灣原住民族運動史料彙編). Now minister of the Council of Indigenous Peoples, Icyang was a key figure in various early Aboriginal movements.

It seemed like a simple and harmless request, but the process took almost 10 years. On Aug. 1, 1994, National Assembly finally granted the request along with an article in the constitution to protect indigenous rights. Aboriginal activists continue to fight for various issues today, but the rectification of their designation was seen was seen as a major victory to a long-mistreated people. Since 2005, Aug. 1 has been observed in Taiwan as Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

A PURE NAME

Photo: Hsieh Wen-hua, Taipei Times

In 1983, along with two other Aboriginal National Taiwan University students, Icyang launched the publication High Green Mountain (高山青), which highlighted the danger of Aboriginal cultural extinction and called for Aborigines to start a self-help movement.

“Through looking at their own situation, they hoped to awaken an Aboriginal consciousness,” Iwan Nawi writes in the book, Taiwan’s Aboriginal Movement at the Legislative Yuan (原住民運動與國會路線). “Although this consciousness originated on campus, it quickly spread through the urban Aboriginal population as well as urban mainstream society.”

Icyang writes that the Aboriginal Rights Association was originally to be named “High Mountain Tribe Rights Association” (高山族權利促進會), but a month before the organization launched, current Kaohsiung Bureau of Education Director Fan Sun-lu (范巽綠) proposed that they use the term Aboriginal instead. The term was formally adopted after an intense debate during the organization’s first meeting.

Photo: Lu Chun-wei, Taipei Times

“It was a pure term because it had never been officially used before,” Icyang writes. “The use of the term symbolizes the fact that our organization not only sought to resolve tangible Aboriginal social issues, it also fought for our status as well.

“We not only want to have our people identify with being Aborigines, through the term we also want to let the Han Chinese know that this land originally belonged to us. We will not dwell on the methods through which they obtained this land, but they should at least respect our rights and status.”

The newly-formed Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) supported the movement, using the designation in its party constitution written in 1986. The same year, the Presbyterian Church also officially adopted the designation, and usage spread among the church’s roughly 80,000 Aboriginal members.

Photo: Taipei Times

CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGE

But the push for the government to formally eliminate “mountain compatriots” in favor of “Aborigines” did not take shape until 1991.

That year, the National Assembly convened to amend the constitution. One of the agenda items concerned guaranteed seats in the Legislature for “mountain compatriots.” If passed, this would be the first time the hated designation appeared in the constitution.

Icyang and other protestors marched to the National Assembly meeting grounds at Yangmingshan’s Zhongshan Hall, and after being blocked by security several times, managed to deliver their petition. They made several requests, but Icyang says that the designation change was the only one reported by the media. To his dismay, no action was taken.

The National Assembly convened again to amend the constitution a year later, and this time more than 1,000 protestors marched to Zhongshan Hall. Icyang writes that the ruling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was hesitant to designate the Aborigines as the original owners of the land, because that would imply that the Han Chinese were a foreign people and the KMT a foreign regime, leading to further problems. The National Assembly then suggested zaozhumin (早住民, or earlier inhabitants) or xianzhumin (先住民, or first inhabitants), which the activists deemed unacceptable.

By the end of the session, Icyang and his people remained “mountain compatriots.”

The DPP backed the Aborigines during the constitution amendment session of 1994. In April, then-president Lee Teng-hui (李登輝), who had opposed the designation change in 1992, publicly addressed the “mountain compatriots” as Aborigines in a speech. This likely prompted the reticent KMT to add the designation change to their agenda as well.

In June, 3,000 people marched for Aboriginal rights. A month later Lee promised Aboriginal activists that they would get their wish. The assembly voted 196-63 in favor.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

This month the government ordered a one-year block of Xiaohongshu (小紅書) or Rednote, a Chinese social media platform with more than 3 million users in Taiwan. The government pointed to widespread fraud activity on the platform, along with cybersecurity failures. Officials said that they had reached out to the company and asked it to change. However, they received no response. The pro-China parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), immediately swung into action, denouncing the ban as an attack on free speech. This “free speech” claim was then echoed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC),

Exceptions to the rule are sometimes revealing. For a brief few years, there was an emerging ideological split between the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) that appeared to be pushing the DPP in a direction that would be considered more liberal, and the KMT more conservative. In the previous column, “The KMT-DPP’s bureaucrat-led developmental state” (Dec. 11, page 12), we examined how Taiwan’s democratic system developed, and how both the two main parties largely accepted a similar consensus on how Taiwan should be run domestically and did not split along the left-right lines more familiar in

Many people in Taiwan first learned about universal basic income (UBI) — the idea that the government should provide regular, no-strings-attached payments to each citizen — in 2019. While seeking the Democratic nomination for the 2020 US presidential election, Andrew Yang, a politician of Taiwanese descent, said that, if elected, he’d institute a UBI of US$1,000 per month to “get the economic boot off of people’s throats, allowing them to lift their heads up, breathe, and get excited for the future.” His campaign petered out, but the concept of UBI hasn’t gone away. Throughout the industrialized world, there are fears that

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.