These days, even 3-year-olds wear headphones, and as the holidays approach, retailers are well stocked with brands that claim to be “safe for young ears” or to deliver “100 percent safe listening.” The devices limit the volume at which sound can be played; parents rely on them to prevent children from blasting, say, Rihanna at hazardous levels that could lead to hearing loss.

But a new analysis by The Wirecutter, a product recommendations Web site owned by The New York Times, has found that half of 30 sets of children’s headphones tested did not restrict volume to the promised limit. The worst headphones produced sound so loud that it could be hazardous to ears in minutes.

“These are terribly important findings,” said Cory Portnuff, a pediatric audiologist at the University of Colorado Hospital, who was not involved in the analysis. “Manufacturers are making claims that aren’t accurate.”

Photo: Reuters/Andrew Couldridge

The new analysis should be a wake-up call to parents who thought volume-limiting technology offered adequate protection, said Blake Papsin, chief otolaryngologist at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

“Headphone manufacturers aren’t interested in the health of your child’s ears,” he said. “They are interested in selling products, and some of them are not good for you.”

Half of 8 to 12-year-olds listen to music daily, and nearly two-thirds of teenagers do, according to a report last year with more than 2,600 participants. Safe listening is a function of volume and duration: The louder a sound, the less time you should listen to it.

It is not a linear relationship. Eighty decibels is twice as loud as 70 decibels, and 90 decibels is four times louder.

Exposure to 100 decibels, about the volume of noise caused by a power lawn mower, is safe for just 15 minutes; noise at 108 decibels, however, is safe for less than three minutes.

85 DECIBELS

The workplace safety limit for adults, set by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health in 1998, is 85 decibels for no more than eight hours. But there is no mandatory standard that restricts the maximum sound output for listening devices or headphones sold in the United States.

When cranked all the way up, modern portable devices can produce sound levels from 97 to 107 decibels, a 2011 study found.

A team at The Wirecutter used two types of sound to test 30 sets of headphones and earbuds with an iPod Touch. First, they played a snippet of Major Lazer’s hit Cold Water as a real-world example of the kind of thumping music children listen to all the time.

Second, the testers played pink noise, usually used to test the output levels of equipment, to see whether the headphones actually limited volume to 85 decibels.

Playing 21 seconds of Cold Water at maximum volume, half of the 30 headphones exceeded 85 decibels. The loudest headphones went to 114 decibels.

With pink noise, roughly one-third exceeded 85 decibels; the loudest was recorded at 108 decibels. Complete results are available at thewirecutter.com.

To pinpoint the earbuds that did reduce volume, the Wirecutter team hooked up a computer to a simulated ear with a microphone inside and a coupler that models the acoustics of an ear canal.

Brian Fligor, an audiologist who is a member of the WHO’s working group on safe listening devices, advised the team on how to compare its results to data on the 85-decibel workplace limit. (Headphones and earbuds are much closer to the ear, obviously; the workplace limit was devised with open areas in mind.)

Lauren Dragan, an editor at The Wirecutter, also corralled a half-dozen children, 3 to 11 years old, to try on each model, choose favorites and compile a “hate list” of ones they would never use.

TODDLER AND TWEEN FAVORITE

In the end, the overall pick for the children was a Bluetooth model called the Puro BT2200 (US$99.99). The headphones were well-liked by both toddlers and tweens, had excellent sound quality, offered some noise cancellation features and adequately restricted volume as long as the cord wasn’t used.

The battery lasts an impressive 18 to 22 hours, and the wired connection is used only as a backup. But that cord must be plugged in as labeled, with one particular end to the headphones and the other to the music device. If inserted the wrong way, “it’ll play really loud,” said Brent Butterworth, an audio expert who helped test all the headphones.

“If they are using it in Bluetooth mode, it’s impossible to make too loud,” he added.

Even with headphones that effectively limit maximum sound, supervision is crucial. “Eighty-five decibels isn’t some magic threshold below which you’re perfectly safe and above which your ears bleed,” Fligor said.

Audiologists offered some tips for listening: First, keep the volume at 60 percent. Second, encourage your child to take breaks every hour to allow the hair cells in the inner ear to rest. Nonstop listening can eventually damage them.

Finally, Jim Battey, director of the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, offered this practical rule: If a parent is an arm’s length away, a child wearing headphones should still be able to hear when asked a question.

Let that sink in: If they can’t hear you, “that level of noise is unsafe and potentially damaging,” Battey said.

Whether this generation of children suffers greater hearing loss than previous ones is the subject of scientific debate. Studies have shown mixed results.

Last week the story of the giant illegal crater dug in Kaohsiung’s Meinong District (美濃) emerged into the public consciousness. The site was used for sand and gravel extraction, and then filled with construction waste. Locals referred to it sardonically as the “Meinong Grand Canyon,” according to media reports, because it was 2 hectares in length and 10 meters deep. The land involved included both state-owned and local farm land. Local media said that the site had generated NT$300 million in profits, against fines of a few million and the loss of some excavators. OFFICIAL CORRUPTION? The site had been seized

Next week, candidates will officially register to run for chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). By the end of Friday, we will know who has registered for the Oct. 18 election. The number of declared candidates has been fluctuating daily. Some candidates registering may be disqualified, so the final list may be in flux for weeks. The list of likely candidates ranges from deep blue to deeper blue to deepest blue, bordering on red (pro-Chinese Communist Party, CCP). Unless current Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) can be convinced to run for re-election, the party looks likely to shift towards more hardline

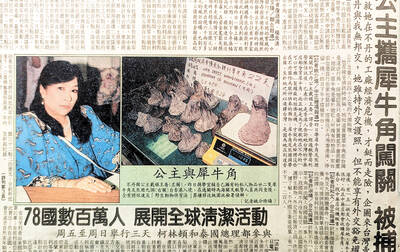

Sept. 15 to Sept. 21 A Bhutanese princess caught at Taoyuan Airport with 22 rhino horns — worth about NT$31 million today — might have been just another curious front-page story. But the Sept. 17, 1993 incident came at a sensitive moment. Taiwan, dubbed “Die-wan” by the British conservationist group Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), was under international fire for being a major hub for rhino horn. Just 10 days earlier, US secretary of the interior Bruce Babbitt had recommended sanctions against Taiwan for its “failure to end its participation in rhinoceros horn trade.” Even though Taiwan had restricted imports since 1985 and enacted

Enter the Dragon 13 will bring Taiwan’s first taste of Dirty Boxing Sunday at Taipei Gymnasium, one highlight of a mixed-rules card blending new formats with traditional MMA. The undercard starts at 10:30am, with the main card beginning at 4pm. Tickets are NT$1,200. Dirty Boxing is a US-born ruleset popularized by fighters Mike Perry and Jon Jones as an alternative to boxing. The format has gained traction overseas, with its inaugural championship streamed free to millions on YouTube, Facebook and Instagram. Taiwan’s version allows punches and elbows with clinch striking, but bans kicks, knees and takedowns. The rules are stricter than the