Taiwan in Time: Oct. 3 to Oct. 9

In May of 1968, Hsieh Hsueh-hung (謝雪紅) was held down by two red guards who forced her to bow her head and admit her wrongdoings. Two years later, before she died in Beijing, she wrote in her will, “I’m not a rightist. I support the Communist Party and socialism.”

Ironically, under the two previous regimes, she was persecuted for being a leftist and served eight years in jail during Japanese rule. She fled to China after leading an armed resistance against Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) troops during the violent suppression of the 228 Incident.

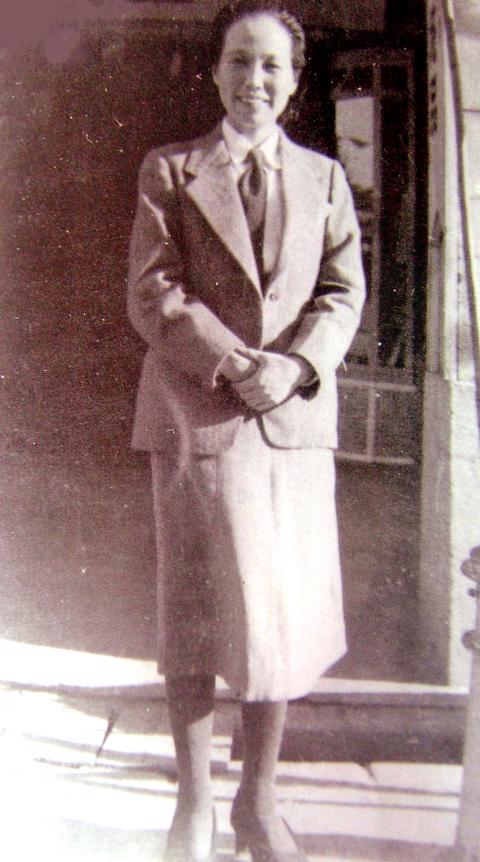

Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Hsieh was born in 1901 to a poor family in Changhua County. At six years old, she would have to hawk bananas in the street and started working in a factory at age 10. When she was 12, she was adopted into a family in Taichung to be their son’s future wife. She ran away due to severe abuse and in 1918 married Chang Shu-min (張樹敏), with whom she traveled to Japan, where she witnessed the “Taisho democracy” period and the aftermath of the rice riots. That was her first time seeing the poor rise up against the wealthy.

Later, they moved to China, where Hsieh’s thinking was further influenced by the May Fourth Movement, a student-led protest against the government. After learning that she was Chang’s concubine, she left him and found a job teaching people how to use sewing machines. She also learned how to read and eventually became involved with Chiang Wei-shui’s (蔣渭水) Taiwan Cultural Association (台灣文化協會), which aimed to passively counter Japanese rule by fostering an awareness of Taiwanese nationalism.

Due to her painful past, she also started championing women’s rights and established herself as an independent woman who ran her own clothing shop. Later, she traveled to China again and enrolled in Shanghai University as a sociology major — the first time she received any type of formal education. During this time, she participated in the May Thirtieth Movement, a labor and anti-imperialist protest that culminated in bloodshed.

JOINING THE CAUSE

Her actions caught the attention of the Chinese Communist Party, who convinced her to join and sent her to further her studies in Moscow. Hsieh was persuaded by the Communist International, an organization to promote communism around the globe, to eventually return to Taiwan and further their cause.

In 1927, she returned to Shanghai to help form the short-lived Taiwanese Communist Party. In addition to the standard communist values, the party also called for an independent Taiwan and denounced Japanese rule as well as emphasizing women’s rights.

Hsieh was soon arrested with several others after the party’s anti-Japanese fliers were discovered by the Japanese police and deported back to Taiwan. After being acquitted, party activities continued under Hsieh’s leadership, eventually taking control of the Taiwanese Peasants’ Union (台灣農民組合) and even trained farmers for an armed rebellion, which never took place.

Hsieh also managed to take control of the Taiwan Cultural Association, turning it into an openly leftist organization. She did the same with Chiang’s Taiwan People’s Party, which by 1931 also had become leftist. During this time, she continued to call for Taiwanese independence.

The group eventually split into factions due to differences in ideology, with Hsieh supporting a Taiwanese identity and involving the bourgeoisie in the revolution, while others were pro-China and called for straight up class struggle. Hsieh was forced out of the party in 1931, and later that year she was arrested in a mass raid of Taiwanese communists and sentenced to 13 years in jail.

In 1939, Hsieh was released due to tuberculosis. She tried to resume her mission, but this was Japan’s expansionist period and all political activities had been banned.

TAIWANESE AUTONOMY

After KMT forces arrived in 1945, Hsieh organized in early October the Taiwan People’s Association (台灣人民協會) along with a number of other leftist organizations, which were eventually forcefully disbanded by the government.

She continued to call for political autonomy for Taiwan, calling for popular elections from governor to township mayor.

“Taiwan must be ruled by Taiwanese,” she declared.

After the 228 Incident broke out, Hsieh was named leader of the resistance in Taichung. They denounced the government’s actions, called for democracy and disarmed the local police. The next day, Hsieh issued a call to arms, stating that Taiwanese should declare war against the dictatorship while warning people not to hurt the recent arrivals from China and not to destroy property.

The resistance eventually failed, and Hsieh fled to Xiamen on March 21, never to return to Taiwan again. During the Anti-Rightist Movement of 1957, she was painted as a rightist partially due to her insistence on Taiwanese political autonomy, and she was purged repeatedly during the Cultural Revolution. She died in 1970, and was not rehabilitated by the party until 1986.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

This month the government ordered a one-year block of Xiaohongshu (小紅書) or Rednote, a Chinese social media platform with more than 3 million users in Taiwan. The government pointed to widespread fraud activity on the platform, along with cybersecurity failures. Officials said that they had reached out to the company and asked it to change. However, they received no response. The pro-China parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), immediately swung into action, denouncing the ban as an attack on free speech. This “free speech” claim was then echoed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC),

Exceptions to the rule are sometimes revealing. For a brief few years, there was an emerging ideological split between the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) that appeared to be pushing the DPP in a direction that would be considered more liberal, and the KMT more conservative. In the previous column, “The KMT-DPP’s bureaucrat-led developmental state” (Dec. 11, page 12), we examined how Taiwan’s democratic system developed, and how both the two main parties largely accepted a similar consensus on how Taiwan should be run domestically and did not split along the left-right lines more familiar in

Many people in Taiwan first learned about universal basic income (UBI) — the idea that the government should provide regular, no-strings-attached payments to each citizen — in 2019. While seeking the Democratic nomination for the 2020 US presidential election, Andrew Yang, a politician of Taiwanese descent, said that, if elected, he’d institute a UBI of US$1,000 per month to “get the economic boot off of people’s throats, allowing them to lift their heads up, breathe, and get excited for the future.” His campaign petered out, but the concept of UBI hasn’t gone away. Throughout the industrialized world, there are fears that

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.