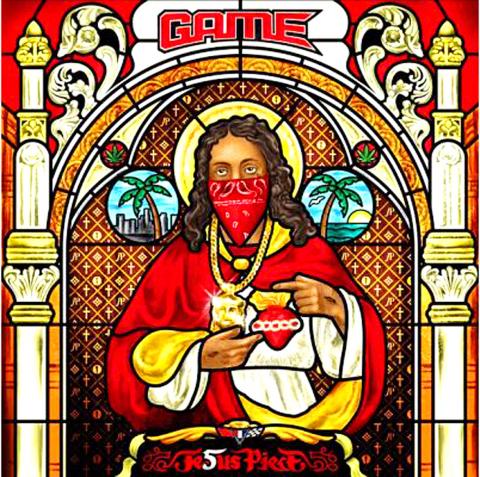

JESUS PIECE

The Game

DGC/Interscope

For the last couple of months, VH1 has been showing the reality show Marrying the Game, which chronicled the wedding preparations of the Game, the abrasive, derivative rapper, and his longtime girlfriend, Tiffney Cambridge. By the end of the season, though, the two were at loggerheads and the wedding was off, at least in part because of the Game’s heavy focus on completing work on Jesus Piece, his fifth album.

Which is a concise way of saying: This album better have been worth it.

Since the beginning of his career, the Game has had a tortured relationship with other rappers: with some he loudly and publicly quibbles, and to others he pledges allegiance in song in a way that transcends admiration into stalker-like obsession. Jesus Piece (DGC/Interscope), as usual, does both of those things, though now that the Game is something of a veteran, his battles have mostly been settled.

Not only is he acknowledging his peers in his rhymes here, but Jesus Piece is also teeming with guests, more guests than a DJ Khaled album: Rick Ross, Lil Wayne, 2 Chainz, Meek Mill, Kendrick Lamar and many more.

Ross’ verse on Ali Bomaye is excellent, and both Lil Wayne, on All That (Lady), and Pusha T, on Name Me King, do more than phone it in. Future delivers a transcendent, lighthearted hook on I Remember. Even Kanye West appears on the chorus of the title track.

Oh, and the Game appears on this album as well. His voice is raspy, and his flow isn’t as rigid as it was early in his career. On Can’t Get Right, he’s almost smooth:

I used to want to be a little Hov

Started with a little rock, got me a little stove

Made a little money, bought me a little Rov’

Sometimes, as on Scared Now, he’s happily reliant on blunt force: “Put three holes in his head like a bowling ball.”

When the Game isn’t rapping about other rappers — which is rare — he is sometimes rapping like other rappers: Pray is a blatant Drake photocopy; on Freedom he sounds like early Jay-Z; and on Celebration he borrows from Bone Thugs-N-Harmony. It’s either lack of originality, or it’s true love — maybe Cambridge was right to call off the wedding. She could never compete.

— JON CARAMANICA, NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

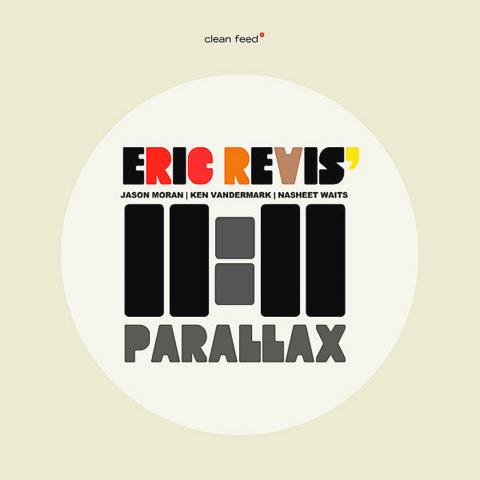

PARALLAX

Eric Revis

Clean Feed

The bassist Eric Revis likes to play strong and loud and is willing to cut across lines of style and tradition to satisfy his need. He’s done it in Branford Marsalis’ Quartet, one of this country’s top-billing jazz groups; in Tarbaby, a trio with the pianist Orrin Evans and the drummer Nasheet Waits; and in a trio led by the German saxophonist Peter Broetzmann, with which he toured last year. That’s a pretty good range, from some baseline verities of the American jazz tradition to free improvising with art-brut appeal.

For his new album, Parallax, he’s found a new forum. Originally, for some 2009 New York club dates, he brought together a quartet with Ken Vandermark on tenor saxophone and clarinet, Jason Moran on piano, and Waits on drums. This is good bridgework, particularly between Vandermark and Moran. Their worlds — in Chicago and New York — don’t overlap much. But they’re close enough. Both use compositional structures and organic group interplay and scholarship to experiment with jazz as a history and a process, revisiting old landmarks, shuffling tradition into new shapes. (They’re both MacArthur Award recipients, for those with scorecards.)

The music, rough and baleful, seems to have pretty old time-stamps on it, though. Much of “Parallax” sounds to me like the ‘80s or early ‘90s, reminiscent in passing of music by John Carter, Tim Berne, David S. Ware and many blended-together nights at the old Knitting Factory on Houston Street. It can sound like research into a variety of strategies: marches, groove, free rhythm; solo-bass features, sometimes double-tracked; blues language and collective improvisation; a Bob Kaufman poem interpreted variously in music by the band members; originals with small or jagged melodies and reworked old songs. (There are two pieces of old-time repertory: an emphatic, stomping version of Jelly Roll Morton’s Winin’ Boy Blues and a more indirect and wild paraphrasing of Fats Waller’s I’m Gonna Sit Right Down and Write Myself a Letter.)

The record is searching for a partnership of sound, and so the action pulls toward Moran and Waits, who have one: they’ve played together for more than a decade and instinctively lock together through feel and dynamics. Some of the album’s thrills, like the tossing, tumbling passages in the middle of Hyperthral, Split and IV, are essentially theirs. Revis follows his own internal mandate to be stormy or forthright in his improvising, and so does Vandermark, but they can seem isolated within the project. The record’s a good idea, and a good start; the band needs more time to gestate.

— BEN RATLIFF, NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

SOLO, VOLUME I

Ryan Blotnick

Self-released

Ryan Blotnick, a guitarist approaching 30, has maintained a slippery self-containment in enough sociable settings — with the saxophonists Michael Blake, Pete Robbins and Bill McHenry; the Akoya Afrobeat Ensemble; and a range of musicians from Copenhagen, Denmark, where he earned a graduate degree — that he’s a strong candidate for a solo album. He’s not afraid of starkness or silence, and he knows how to spin a good yarn. He’s a natural.

Which isn’t to say that he skimps on preparation. Solo, Volume I, available as a pay-what-you-wish download at ryanblotnick.bandcamp.com, is a product of several summers in his home state of Maine spent working in hotels, restaurants and other for-hire settings. (On one wedding-services website, his customer rating is a perfect 5.0.) The album clocks in under 35 minutes and gives the sense of an intensely thoughtful design.

Blotnick clearly knows the tradition he’s accessing here. Lenny’s Ghost, the album’s longest track, is his nod to Lenny Breau; elsewhere he touches on the stark lyricism of John Fahey and the intricate fingerpicking technique of Leo Kottke. Dreams of Chloe, a wakening ballad processed with light distortion, and Hymn for Steph, a sober country waltz, evoke the recent solo guitar recordings of Marc Ribot. The Ballad of Josh Barton suggests a close study of some early acoustic Neil Young.

Every track but one was recorded with a 1959 Martin guitar — an acoustic model, but one with a pickup and volume and tone controls built in — and no overdubs or other studio manipulations. The sound, mixed and mastered by Marc Bartholomew, is pristine enough that you hear Blotnick’s fingertips lightly scudding across the strings. And the atmosphere is such that every liberty registers are both audacious and reasonable.

What’s missing from the album is any palpable impression of danger, a feeling that Blotnick is reaching beyond his carefully honed capacities. That’s acceptable, on an album so defined by intelligent restraint. And it raises certain expectations: by titling the album Solo, Volume I, Blotnick implies that there’s more of this to come.

— NATE CHINEN, NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.

Many people in Taiwan first learned about universal basic income (UBI) — the idea that the government should provide regular, no-strings-attached payments to each citizen — in 2019. While seeking the Democratic nomination for the 2020 US presidential election, Andrew Yang, a politician of Taiwanese descent, said that, if elected, he’d institute a UBI of US$1,000 per month to “get the economic boot off of people’s throats, allowing them to lift their heads up, breathe, and get excited for the future.” His campaign petered out, but the concept of UBI hasn’t gone away. Throughout the industrialized world, there are fears that

Taiwan’s democracy is at risk. Be very alarmed. This is not a drill. The current constitutional crisis progressed slowly, then suddenly. Political tensions, partisan hostility and emotions are all running high right when cool heads and calm negotiation are most needed. Oxford defines brinkmanship as: “The art or practice of pursuing a dangerous policy to the limits of safety before stopping, especially in politics.” It says the term comes from a quote from a 1956 Cold War interview with then-American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, when he said: ‘The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is

Like much in the world today, theater has experienced major disruptions over the six years since COVID-19. The pandemic, the war in Ukraine and social media have created a new normal of geopolitical and information uncertainty, and the performing arts are not immune to these effects. “Ten years ago people wanted to come to the theater to engage with important issues, but now the Internet allows them to engage with those issues powerfully and immediately,” said Faith Tan, programming director of the Esplanade in Singapore, speaking last week in Japan. “One reaction to unpredictability has been a renewed emphasis on