If you were one of the lucky ones who sat face to face with Marina Abramovic during her marathon sittings—some 10 hours long—at New York’s MoMA in 2010, you might now find yourself in The Artist Is Present, a documentary by Matthew Akers which opens in the UK this week. People smiled and cried and stared; so did Abramovic. “The hardest thing is to do something which is close to nothing,” says the film poster, quoting the artist.

I have had my own encounters with Abramovic in the past, and once took part in a workshop she directed. We all wore white coats. There were slow walks, breathing lessons and therapeutic exercises. At the end, I wondered if a light colonic cleansing might be afoot. Last year, at the Manchester International Festival, I watched her life retold in Robert Wilson’s epic theatrical extravaganza, The Life and Death of Marina Abramovic, starring the artist herself, and now set to go on a European tour. Marina suffers at the hands of her mother, and seems to die not once but three times.

Whatever extremes Abramovic has gone to in her art, sometimes whipping and cutting herself, others have travelled further. There have been the extremes of 1960s Viennese Actionism, with its blood orgies and dead cows and sexual excess; and the silliness and self-indulgences of 1970s California performance art. Both movements predated and inspired Abramovic’s outre, alarming and sometimes gruelling performances. In 1971, the US artist Chris Burden had himself shot in the arm by a friend; the following year, in Deadman, he lay under a tarpaulin on the highway, illuminated by flares, as the night-time traffic roared by. Artists have had themselves suspended from the ceiling by fish hooks and stood naked in the filthiest of Chinese public toilets. They have cut, burned and excoriated themselves with no less vigour than medieval saints and penitents.

Photo: Reuters

Suffering for your art is one thing; suffering as your art is another. When artist Ryan McNamara and collaborator Sam Roeck buried themselves up to the neck in the grounds of Robert Wilson’s Watermill Performance Center in upstate New York last year, and sang love duets to one another (“Tonight” from West Side Story and Dolly Parton numbers featured on the playlist), they were both accidentally trodden on and kicked in the head by a clumsy audience member. This much-reported incident became an inadvertent part of the performance (performed as part of Wilson’s 70th birthday bash), and it is difficult to see their pain as anything other than comedy. Samuel Beckett would have laughed.

Performance art no longer looks like a gallery sideshow, an add-on to the museum experience. In two weeks’ time, Tate Modern will launch its new Tanks space with a 15-week festival of live performance, installation and film and video works; meanwhile British-German artist Tino Sehgal, who has worked with singing gallery attendants and performing children, is the next to take on the gallery’s Turbine Hall. Tate describes the Tanks as “the world’s first museum galleries permanently dedicated to exhibiting live art, performance, installation and film works;” but the institution is only catching up with what artists have been doing for a very long time. Performance, in fact, is now where it’s at; it’s hard to think of much recent art that isn’t, at some level, performative.

And who cares about genre any more, anyway? The collaborations between artists and dancers and composers that made New York so vital in the 1960s were no mere historical blip. Younger generations of artists have taken their cues from the freedoms and opportunities different media, and different disciplines, have afforded them.

Photo: AFP

The proliferation of performance in museums has a lot to do with both art itself and the changing role of these institutions, as well as the demands of an audience that wants to feel empowered, engaged and participatory. Today’s spectators demand a role, whether they are inventing their own performances in the gallery (both Olafur Eliasson’s and Ai Weiwei’s Tate Modern installations seemed to invite all kinds of unexpected audience behaviour), or clamouring to take part in artist-led workshops such as the Hayward Gallery’s on-going Wide Open School. We want to be active, rather than passive spectators. Perhaps this is merely fashion, but I suspect not.

Wander any “immersive installation,” and you feel like an actor. Walking through the nether regions of an Elmgreen & Dragset installation, or one of Gregor Schneider’s haunted houses, or a show by Anri Sala, you are not always sure if some of the people you meet aren’t paid plants.

This doesn’t mean you can’t just go and look at a painting or a sculpture any more; it does mean that you frequently find yourself surrounded by objects that are themselves the residue of some kind of performance. This is as true of a Jackson Pollock painting as it is of the little brown miseries contained in Joseph Beuys’ vitrines (which were often the tokens of his earlier performances). It is true of the props and stages left in a gallery after a Spartacus Chetwynd performance.

Most art, in any case, is the result of some kind of studio-bound, solitary performance. It doesn’t matter whether that performance involved wearing a hat and holding a palette and brushes (Goya, in his 1790-1795 self-portrait), or, as in a performance by Simon Fujiwara about his dawning sexuality in Cornwall, south-west England, getting an erection in front of an abstract painting by (Cornwall-based artist) Patrick Heron. The presentation of art works, of history, is always a kind of staging.

Performance can be mystifying and magical, troubling and captivating. Tino Sehgal’s performances, or those of Sharon Hayes, make us think; Hayes’s confrontational performances sometimes mimic political demonstrations, a mix of theater and protest. The rhyming couplets and video-plays of Mary Reid Kelley, with their daft costumes and makeup, are as much performances as stories on film. Somewhere in there is a kind of truth. Artists have backed into the theatrical, and into performance, into dance and play-writing while attempting to do other things.

One might talk of a choreography of objects and spaces as much as of people in Martin Creed’s work, and even Roman Ondak’s queues and crowds of the performing public become dance-like in their utter simplicity: people form a queue, or fill a room and then leave again.

A couple of weeks ago, at Documenta in Kassel, I was disarmed and disturbed watching Belgian choreographer Jerome Bel direct a troupe of actors—all of whom are mentally challenged in one way or another—step to the front of the stage, one by one, and stand there in silence for a minute. Time lengthened and contracted, for the audience as well as the performers. Later, among other requests, Bel got each of them to name their disability, as best they could. Then they sang, they danced, they said what they thought about Bel’s piece.

Was this theatre, art, a “freak show” (as one performer reported her sister saying after watching one performance), or something else? It was an exercise in real presence, of difficulty and empathy, focus and lapse. It was very moving. Private rituals and public acts, catharsis and confrontation are the central strands of art as performance. The work is the beginning of a dialogue, not an end. It is something shared. We are all performers, even when we are playing at being spectators.

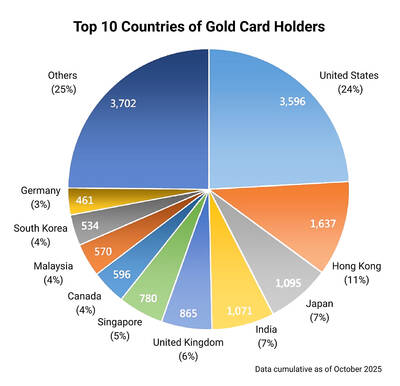

Seven hundred job applications. One interview. Marco Mascaro arrived in Taiwan last year with a PhD in engineering physics and years of experience at a European research center. He thought his Gold Card would guarantee him a foothold in Taiwan’s job market. “It’s marketed as if Taiwan really needs you,” the 33-year-old Italian says. “The reality is that companies here don’t really need us.” The Employment Gold Card was designed to fix Taiwan’s labor shortage by offering foreign professionals a combined resident visa and open work permit valid for three years. But for many, like Mascaro, the welcome mat ends at the door. A

If China attacks, will Taiwanese be willing to fight? Analysts of certain types obsess over questions like this, especially military analysts and those with an ax to grind as to whether Taiwan is worth defending, or should be cut loose to appease Beijing. Fellow columnist Michael Turton in “Notes from Central Taiwan: Willing to fight for the homeland” (Nov. 6, page 12) provides a superb analysis of this topic, how it is used and manipulated to political ends and what the underlying data shows. The problem is that most analysis is centered around polling data, which as Turton observes, “many of these

Divadlo feels like your warm neighborhood slice of home — even if you’ve only ever spent a few days in Prague, like myself. A projector is screening retro animations by Czech director Karel Zeman, the shelves are lined with books and vinyl, and the owner will sit with you to share stories over a glass of pear brandy. The food is also fantastic, not just a new cultural experience but filled with nostalgia, recipes from home and laden with soul-warming carbs, perfect as the weather turns chilly. A Prague native, Kaio Picha has been in Taipei for 13 years and

Since Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) was elected Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair on Oct. 18, she has become a polarizing figure. Her supporters see her as a firebrand critic of the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), while others, including some in her own party, have charged that she is Chinese President Xi Jinping’s (習近平) preferred candidate and that her election was possibly supported by the Chinese Communist Party’s (CPP) unit for political warfare and international influence, the “united front.” Indeed, Xi quickly congratulated Cheng upon her election. The 55-year-old former lawmaker and ex-talk show host, who was sworn in on Nov.