I always wanted to own a dream car,” said Andy Saunders, 44, who has a flair for customizing cars. “But others had already bought all the dream cars.”

So Saunders settled, instead, for a nightmare.

“I remember one day going through a book about dream cars, and I saw a tiny drawing, a sketch really, or artist's impression of a car called the Aurora,” Saunders said in a telephone interview. “My dad commented, ‘Have you ever seen anything so ugly?' He was right; it was so ugly it was unreal. I said straightaway, ‘I've got to own that.'”

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Saunders, who operates an auto importing and customizing business near his home in England, said he enjoyed a challenge. He has worked on cars that include a Lancia and a Cord (www.andysaunderskustoms.com).

He saw the image of the Aurora in 1993, and it took him several years of detective work to find what happened to the car.

The Aurora may have had the most unusual pedigree in the history of the auto industry. It was created in the mid-1950s by a Catholic priest, Alfred Juliano, and partly bankrolled by parishioners of his church in Branford, Connecticut.

Juliano wanted to create the world's safest automobile, and his Aurora featured innovations that were years ahead of their time. The Aurora also had many wacky ideas to go along with its bizarre styling. Some auto historians have called it the ugliest car ever made.

Although Saunders originally agreed, he has come to see beauty in the Aurora.

Juliano, who studied art, said he always wanted to design cars, even as he studied to join the priesthood. Published reports said he entered competitions for aspiring auto stylists, including one sponsored by General Motors. Juliano's family said GM offered him a scholarship to study with the legendary designer Harley Earl, but he said the offer came just after he had been ordained a priest.

Juliano continued to be fascinated with cars and their design. He also believed that most cars were unsafe, and began a quest to design a car that addressed his laundry list of safety issues. His solutions were novel, to say the least.

“Despite having no mechanical knowledge, Juliano set out to put his heart and soul into that car,” Saunders said. “He bought a totaled 1953 Buick, straightened the frame, and began building his dream around that.” He spent two years designing the car and another two constructing it.

Over a plywood substructure, Juliano fashioned a swoopy 5.5m-long fiberglass body, which he said was resistant to dents, rust and corrosion. It had a gaping, cow-catcher-style nose, filled with foam, to safely scoop up errant pedestrians and cradle them on a kind of platform. The spare tire was in a “crush space” under the nose.

Hydraulic jacks, activated by a dashboard control, lifted the Aurora off the ground for service.

The oddly bubble-shaped windshield, made from shatterproof resin, had no wipers because Juliano said it was so aerodynamic, raindrops blew away. The bubble curved out, away from occupants, to minimize head injuries. The roof was a stunning panoramic dome, with metal blinds inside.

The driver's seat was toward the center of the car, for better protection in a side impact. There were four seats, each with seat belts, still a revolutionary idea at the time.

The seats had high, reinforced backs and were mounted on a pedestal that could be rotated so, in case of an impending crash, they could be spun backwards.

Other safety innovations included a roll cage, side-impact bars, a collapsible steering column and a padded instrument panel.

Although the prototype cost US$30,000 to build, Juliano calculated that he could produce copies for US$12,000 and make a profit. At the time, the most expensive American car, by far, was a Cadillac Eldorado Brougham priced around US$13,000. He planned to offer buyers a choice of engines, mostly from GM.

Where Juliano got it all wrong was in the drivetrain. The Buick's engine had not been started in more than four years.

Worse, he did not clean out the fuel lines before scheduling a media event in New York City in 1957, to which he planned to drive the Aurora for its world introduction.

He arrived hours late, because the Aurora broke down 15 times en route and needed to be towed to garages to have its fuel system purged of gunk. Although New Yorkers marveled at the futuristic-looking machine when it finally arrived, they had no reason to be impressed by its performance, especially relative to its price tag.

Things went from bad to worse for both Juliano and the Aurora. Questions were raised — no one seems clear who started this — about Juliano's finances. He said he thought it was all instigated by GM, which denied involvement.

Juliano compared himself to Preston Tucker, who had asserted that he was harassed out of business by other automakers when he tried to manufacture the Tucker in the late 1940s.

Juliano was eventually accused by his superiors of misappropriating parishioners' donations. The Internal Revenue Service opened investigations into possible tax liabilities.

But Juliano was actually deeply in debt because of the project. He had no source of funds to begin production, even if he had received orders (which he had not).

Finally, Juliano declared bankruptcy. He forfeited the Aurora to a garage where he had an unpaid repair bill. He was forced to leave the Order of the Holy Ghost.

For decades, the Aurora lay forgotten and rotting in a field behind the garage. Juliano had a brain hemorrhage while reading in a library and died a few months later in 1989.

“I think the whole story is so sad,” Saunders said. “He died a broken man, because he lost his dream.”

Saunders found the Aurora through an old photo, which had a billboard for the repair shop in the background. He reached the shop's owner and arranged to buy the car for US$1,500, sight unseen, and have it shipped to England.

The car was in disastrous shape. “It had mostly melted,” Saunders recalled. “I wish I had never laid eyes on it.”

But he persevered for years and finished the car.

“I have never found anyone who could replicate Juliano's astounding workmanship, in areas like the fiberglass bodywork or that Perspex windscreen,” he said. “I've done the best job of re-creating it I could.”

Saunders' restoration was rewarded when he was invited to show the car two years ago at the prestigious Goodwood Festival of Speed in England.

Since then, it has been displayed at the National Motor Museum at Beaulieu, Hampshire (beaulieu.co.uk), and, true to its heritage, has been in and out of repair shops for assorted maladies.

Saunders said he believed the Aurora deserved a place of honor in automotive history.

“If anybody would have listened to him, he could have changed the face of motoring,” Saunders said of Juliano. “But for the time, he was just too far out there.”

Last week the story of the giant illegal crater dug in Kaohsiung’s Meinong District (美濃) emerged into the public consciousness. The site was used for sand and gravel extraction, and then filled with construction waste. Locals referred to it sardonically as the “Meinong Grand Canyon,” according to media reports, because it was 2 hectares in length and 10 meters deep. The land involved included both state-owned and local farm land. Local media said that the site had generated NT$300 million in profits, against fines of a few million and the loss of some excavators. OFFICIAL CORRUPTION? The site had been seized

Next week, candidates will officially register to run for chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). By the end of Friday, we will know who has registered for the Oct. 18 election. The number of declared candidates has been fluctuating daily. Some candidates registering may be disqualified, so the final list may be in flux for weeks. The list of likely candidates ranges from deep blue to deeper blue to deepest blue, bordering on red (pro-Chinese Communist Party, CCP). Unless current Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) can be convinced to run for re-election, the party looks likely to shift towards more hardline

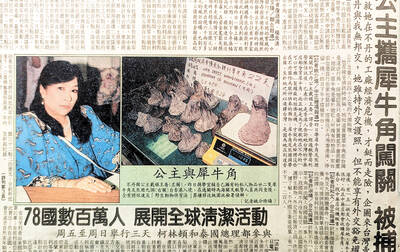

Sept. 15 to Sept. 21 A Bhutanese princess caught at Taoyuan Airport with 22 rhino horns — worth about NT$31 million today — might have been just another curious front-page story. But the Sept. 17, 1993 incident came at a sensitive moment. Taiwan, dubbed “Die-wan” by the British conservationist group Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), was under international fire for being a major hub for rhino horn. Just 10 days earlier, US secretary of the interior Bruce Babbitt had recommended sanctions against Taiwan for its “failure to end its participation in rhinoceros horn trade.” Even though Taiwan had restricted imports since 1985 and enacted

Enter the Dragon 13 will bring Taiwan’s first taste of Dirty Boxing Sunday at Taipei Gymnasium, one highlight of a mixed-rules card blending new formats with traditional MMA. The undercard starts at 10:30am, with the main card beginning at 4pm. Tickets are NT$1,200. Dirty Boxing is a US-born ruleset popularized by fighters Mike Perry and Jon Jones as an alternative to boxing. The format has gained traction overseas, with its inaugural championship streamed free to millions on YouTube, Facebook and Instagram. Taiwan’s version allows punches and elbows with clinch striking, but bans kicks, knees and takedowns. The rules are stricter than the