Online scams are a huge business. More than that, they have become a full industry with sophisticated supply chains of services, equipment and labor. Key groups in this sector also have direct connections to nations such as Russia, China and North Korea. What has long seemed just a lot of low-level crime has grown into a global, geopolitical problem.

You are still your own best defense against losing money to online scammers, but the volume and sophistication of attacks are only increasing. Governments must do more to help defend their people, companies and institutions.

Cybercrime is a national security issue, and the entire system from major hacking attacks to everyday phishing should be taken as seriously as drug trafficking or terrorist financing.

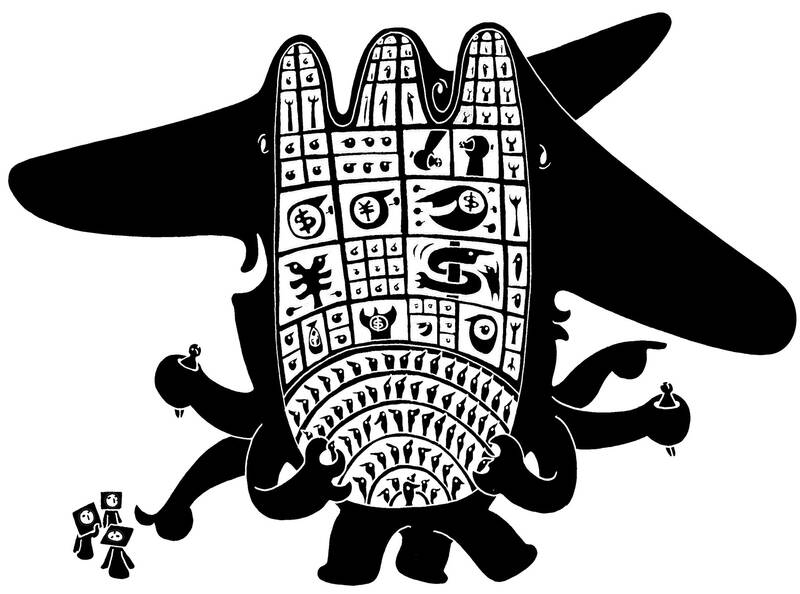

Illustration: Mountain People

To be fair, the problems have not been completely ignored, but national efforts have tended to focus on large-scale and direct ransomware attacks on states themselves, or their biggest services, such as healthcare.

However, these are just the tip of a massive iceberg.

Worldwide losses are hard to track, but potentially huge. The Global Anti-Scam Alliance, a group formed of technology and finance companies as well as specialist consultants, estimates that in the past couple of years consumers collectively have lost more than US$1 trillion each year to scammers. That is the same as Switzerland’s GDP.

“The amounts being lost and the harm being done grows every year,” alliance managing director Jorij Abraham tells me. “The proceeds are used to fund other types of crime but also are reinvested in better technologies to improve the scam, using for example AI [artificial intelligence], or to increase the reach of the scam, with marketing budgets of millions being used to advertise scams.”

The Google Threat Intelligence Group, part of Alphabet Inc, reported on the links between cybercriminal groups and state interests for this month’s Munich Security Conference. Some state-sponsored groups have crime as a sideline to supplement their budgets and some crime organizations are used by government on a casual basis for specific, larger-scale attacks, data thefts or espionage. All are part of the same underground industry.

In the past few years, Abraham says researchers have seen a sharp rise in crime syndicates across the globe with a strong specialization in one type of scam, for example online shopping, investment, romance, subscriptions and many others. Criminals continuously improve their schemes and document how they can best be executed. Then they export the tools, scripts and methods around the world.

Victims can often get hit repeatedly, too. In 2020 and 2021, while talking to victims of binary options trading scams, one truly shocking aspect I often heard was people’s stories of being contacted by supposed law firms with offers to help recover their losses, which turned out to be yet another drain on the savings of those who fell for it.

At that time, Abraham’s group was gathering reports about a then-new trend of mainly Taiwanese and Chinese being duped by offers of well-paid work in Southeast Asia, only to find themselves trafficked as indentured labor for scam groups.

“On arrival, their passports are taken, and they are sold to different groups and forced to work in offices running illegal phone or online scams,” Abraham’s global scam report for 2022 notes. “Taiwan authorities say almost 5,000 citizens have been recorded traveling to Cambodia and not returning.”

Things have gotten worse: A recent podcast series from The Economist interviewed people who had been trafficked from the Philippines, countries in Africa and elsewhere, who described their lives in a walled-off “scam town” deep in the countryside of Myanmar. Relatively well-off Westerners being bilked out of their savings are not the only victims.

Part of the reason governments and security services have been slow to react might be that most fraud cases are individually small, so the cost of investigating them is not worth it.

However, those small incidents still add up to big profits for the industry. In the UK, for example, about 82 percent of cases are worth less than £1,000 (US$1,260) each, but in total they still account for 12 percent of all losses, according to data from UK Finance, a trade group.

Meanwhile, cases worth more than £10,000 make up less than 3 percent by number, but nearly 60 percent of proceeds.

A major worry is that AI tools will make all of this easier and cheaper for criminals — and will make large-scale high-value scams even more difficult to stop. Last year, an employee at a Hong Kong-based company was tricked into sending US$26 million to thieves that used an AI filter on a video call to disguise themselves as the company’s chief financial officer.

Battling scams has mainly been left up to banks, which have spent heavily on compensating customers and investing in education and warning systems in places like the UK.

Finance companies in turn have been crying out for more help from internet and social media companies to track and block bad actors. AI and the spread of crypto are making these efforts less effective.

The Google Threat Intelligence Group’s recommendations for governments include stronger education and awareness campaigns to help people defend themselves, as well as potentially more powers for banks and technology companies to act directly against criminal groups. In truth, countries need to start treating scams and other cybercrime like they do drug trafficking and terror. That means international cooperation on intelligence and enforcement where possible, as well as choking the financial flows through banking networks and crypto exchanges.

What is most troubling is that just as the US is turning its back on exactly this kind of cooperation and enforcement, it is also promising to unshackle crypto and potentially diluting banks’ defenses against dirty money. Other countries will be tempted to follow suit. If that continues, criminals and unfriendly states will get rich and win, while US citizens and other countries will foot the bill.

Paul J. Davies is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering banking and finance. Previously, he was a reporter for the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Congratulations to China’s working class — they have officially entered the “Livestock Feed 2.0” era. While others are still researching how to achieve healthy and balanced diets, China has already evolved to the point where it does not matter whether you are actually eating food, as long as you can swallow it. There is no need for cooking, chewing or making decisions — just tear open a package, add some hot water and in a short three minutes you have something that can keep you alive for at least another six hours. This is not science fiction — it is reality.

A foreign colleague of mine asked me recently, “What is a safe distance from potential People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Rocket Force’s (PLARF) Taiwan targets?” This article will answer this question and help people living in Taiwan have a deeper understanding of the threat. Why is it important to understand PLA/PLARF targeting strategy? According to RAND analysis, the PLA’s “systems destruction warfare” focuses on crippling an adversary’s operational system by targeting its networks, especially leadership, command and control (C2) nodes, sensors, and information hubs. Admiral Samuel Paparo, commander of US Indo-Pacific Command, noted in his 15 May 2025 Sedona Forum keynote speech that, as

In a world increasingly defined by unpredictability, two actors stand out as islands of stability: Europe and Taiwan. One, a sprawling union of democracies, but under immense pressure, grappling with a geopolitical reality it was not originally designed for. The other, a vibrant, resilient democracy thriving as a technological global leader, but living under a growing existential threat. In response to rising uncertainties, they are both seeking resilience and learning to better position themselves. It is now time they recognize each other not just as partners of convenience, but as strategic and indispensable lifelines. The US, long seen as the anchor

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) last week announced that the KMT was launching “Operation Patriot” in response to an unprecedented massive campaign to recall 31 KMT legislators. However, his action has also raised questions and doubts: Are these so-called “patriots” pledging allegiance to the country or to the party? While all KMT-proposed campaigns to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmakers have failed, and a growing number of local KMT chapter personnel have been indicted for allegedly forging petition signatures, media reports said that at least 26 recall motions against KMT legislators have passed the second signature threshold