The overuse of antibiotics is widely recognized as one of the main factors contributing to antimicrobial resistance (AMR), often called the “silent pandemic,” but what is less well-known is that shortages of antibiotics also play a role in fueling it.

Scarce supplies of pediatric amoxicillin, used to treat Strep A, made headlines in the UK late last year, as a surge of infections left at least 19 children dead. From being an outlier, such shortfalls are common and pervasive, affecting countries across the world, and their consequences for individuals’ health and AMR’s spread can be dire.

That is because shortages of first-line antibiotics often lead to overuse of those that are specialized or kept in reserve for emergencies. Not only can these substitutes be less effective, but reliance on them increases the risk of drug resistance developing and infections becoming more difficult to treat in the long-run.

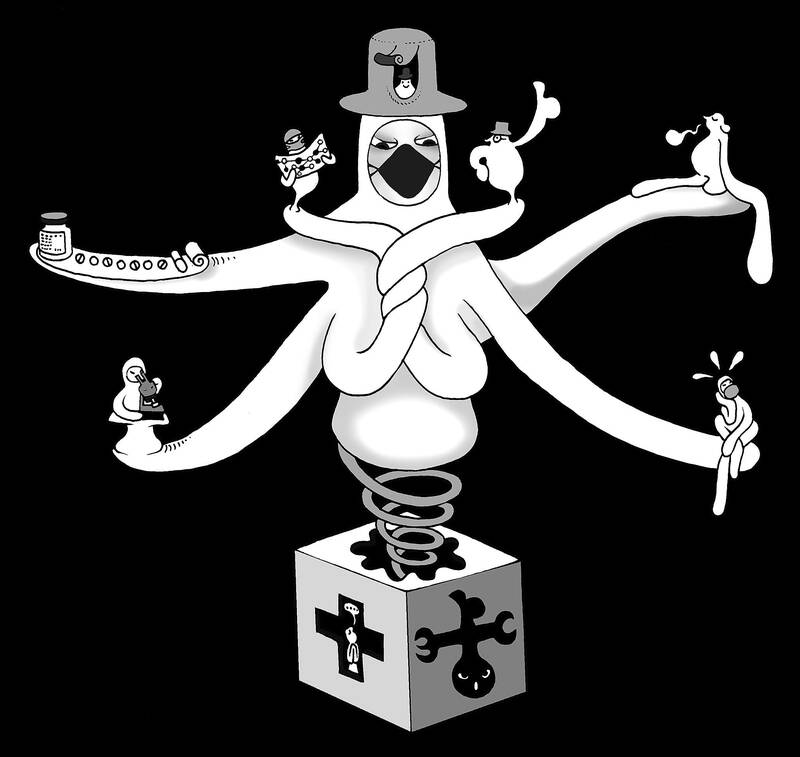

Illustration: Mountain People

Already one of the world’s biggest killers, AMR is on the rise. In 2019, it was directly responsible for an estimated 1.27 million deaths — more than HIV/AIDS and malaria combined — and associated with 4.95 million more.

So far, the global response to this growing crisis has focused mainly on trying to outpace drug-resistant bacteria through the development of new antibiotics.

Yet in the short term, there is ample room to reduce the number of AMR deaths, as well as AMR’s impact on health more broadly, by addressing some of the causes of shortages and improving access to appropriate treatments.

The same market failures that triggered the global AMR crisis are also largely responsible for antibiotic shortages. Compared with other drugs, antibiotics are often more complex and more costly to manufacture, have stricter regulatory requirements and are less profitable. As a result, many pharmaceutical companies have significantly reduced or stopped antibiotic research and development over the past few decades.

Not only are very few new antibiotics being developed, but it has also become less attractive to produce those already on the market, partly due to supply chain bottlenecks and volatility. All it takes is a disruption in the supply of an ingredient or a quality-control problem, or a supplier increasing prices or halting production entirely, to bring the global supply chain of these medicines to a standstill.

Just as important has been the equally volatile demand for antibiotics caused by sudden outbreaks of bacterial infections and poor management of national supplies, which contributes to stockouts. While shortages are not uncommon in the pharmaceutical industry, they are 42 percent more likely for antibiotics than they are for other drugs.

Although precise numbers that would reveal the scale of the problem are difficult to obtain, much of this uncertainty could be avoided with better market intelligence. Even though antibiotics are less lucrative than other drugs, pharmaceutical companies can still turn a profit — if they have accurate data. Improved forecasting can thus reduce risks for manufacturers and provide them with an incentive to scale up production and expand their markets.

There is also plenty of room for improvement in the way that countries — particularly lower-income nations — procure, register and manage these vital drugs.

For example, by expanding the capacity of national regulatory authorities, it would be easier to track and coordinate supplies and create stockpiles to build greater resilience. All of this would also help provide more certainty for drugmakers.

SECURE, an initiative led by the WHO and the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (of which I am executive director), aims to work with countries to improve access to essential antibiotics. That involves exploring how national regulatory authorities could serve as centralized hubs to help monitor, prevent and respond to shortages.

Eventually, SECURE intends to create more buoyant and competitive markets by encouraging countries to pool procurement, ensuring a more reliable supply.

Shortages of antibiotics are a serious problem for all countries, but there is plenty that can — and should — be done to prevent them. Given the accelerating spread of AMR and the long lead-in time to develop antibiotics, the problem can no longer be overlooked.

Equally important, efforts to address scarce supplies could help ensure that, when new drugs become available, they reach the people who need them.

Manica Balasegaram is executive director of the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

There is a modern roadway stretching from central Hargeisa, the capital of Somaliland in the Horn of Africa, to the partially recognized state’s Egal International Airport. Emblazoned on a gold plaque marking the road’s inauguration in July last year, just below the flags of Somaliland and the Republic of China (ROC), is the road’s official name: “Taiwan Avenue.” The first phase of construction of the upgraded road, with new sidewalks and a modern drainage system to reduce flooding, was 70 percent funded by Taipei, which contributed US$1.85 million. That is a relatively modest sum for the effect on international perception, and

At the end of last year, a diplomatic development with consequences reaching well beyond the regional level emerged. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared Israel’s recognition of Somaliland as a sovereign state, paving the way for political, economic and strategic cooperation with the African nation. The diplomatic breakthrough yields, above all, substantial and tangible benefits for the two countries, enhancing Somaliland’s international posture, with a state prepared to champion its bid for broader legitimacy. With Israel’s support, Somaliland might also benefit from the expertise of Israeli companies in fields such as mineral exploration and water management, as underscored by Israeli Minister of

When former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) first took office in 2016, she set ambitious goals for remaking the energy mix in Taiwan. At the core of this effort was a significant expansion of the percentage of renewable energy generated to keep pace with growing domestic and global demands to reduce emissions. This effort met with broad bipartisan support as all three major parties placed expanding renewable energy at the center of their energy platforms. However, over the past several years partisanship has become a major headwind in realizing a set of energy goals that all three parties profess to want. Tsai

On Sunday, elite free solo climber Alex Honnold — famous worldwide for scaling sheer rock faces without ropes — climbed Taipei 101, once the world’s tallest building and still the most recognizable symbol of Taiwan’s modern identity. Widespread media coverage not only promoted Taiwan, but also saw the Republic of China (ROC) flag fluttering beside the building, breaking through China’s political constraints on Taiwan. That visual impact did not happen by accident. Credit belongs to Taipei 101 chairwoman Janet Chia (賈永婕), who reportedly took the extra step of replacing surrounding flags with the ROC flag ahead of the climb. Just