In the advertisement, a woman in a white lace dress makes suggestive faces at the camera and then kneels. There is something a bit uncanny about her; a quiver at the side of her temple, a peculiar stillness of her lip.

However, if you saw the video in the wild, you might not know that it is a deepfake fabrication. It would just look like a video, like the opening shots of some cheesy, low-budget Internet porn.

In top right corner, as the video loops, there is a still image of actress Emma Watson, taken when she was a teenager, from a promotional shoot for the Harry Potter movies. It is her face that has been pasted onto the porn performer’s.

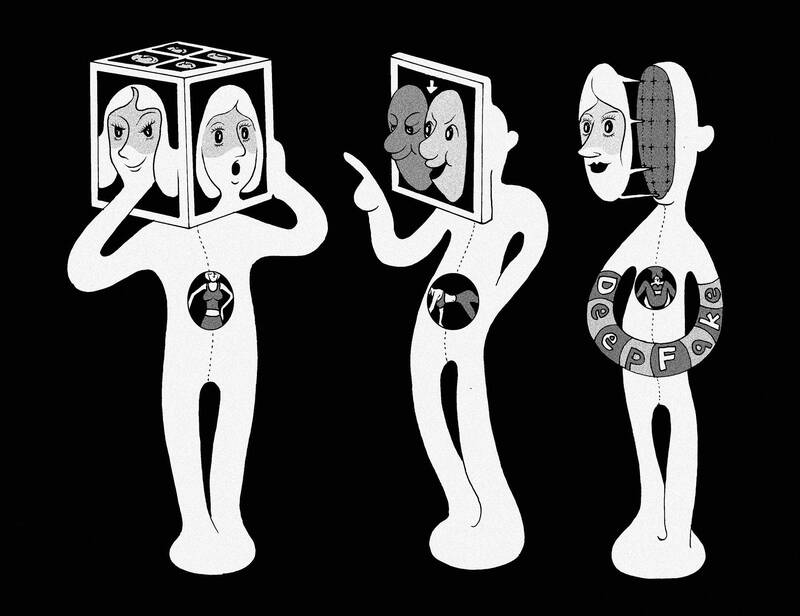

Illustration: Mountain People

Suddenly, a woman who has never performed in pornography is featured in it.

The ads, which directed users to an app that uses artificial intelligence (AI) technology to make deepfake videos, were discovered in more than 230 iterations across Facebook and Instagram, an NBC news investigation led by US journalist Kat Tenbarge found.

Most of the ads featured Watson’s image; some others used the face of actress Scarlett Johansson. The same ads appeared in photo editing and gaming apps available in Apple’s App Store. Lest the message be lost on viewers, the ads make explicit that they are intended to help users create nonconsensual porn of any women they like.

“Swap ANY FACE in the video,” the ads read. “Replace face with anyone. Enjoy yourself with AI face swap technology.”

Similar ads for deepfake services appear directly next to explicit videos on PornHub. Although deepfake technology can theoretically be used for any kind of content — anything from joking satire to malicious political disinformation campaigns — overwhelmingly, the technology is used to create nonconsensual porn.

A report from 2019 showed that 96 percent of deepfake material online is pornographic. That figure might well be increasing.

The ads on Meta and Apple platforms appeared as consumer demand for deepfake pornography is exploding. The surge comes on the heels of a controversy that rocked online video game communities in January, when a popular streamer, Brandon Ewing — who calls himself “Atrioc” — displayed deepfake pornography of several popular female streamers in one of his online broadcasts.

He later admitted to having paid for the artificial porn of the women, who were his colleagues and friends, after seeing an ad similar to those that appeared on Meta and Apple platforms.

The women whose images were commandeered for Ewing’s pornography issued angry and hurt responses; Ewing himself apologized.

However, the controversy seems to have only made the streamer’s overwhelmingly young and male follower base more aware of the availability of deepfake content — and eager to use it themselves.

Genevieve Oh, a researcher who studies livestreaming, told NBC that after Ewing’s apology, Web traffic to the top deepfake porn sites exploded.

That rapid increase over the past few weeks has followed a slower, but still alarming, growth of the deepfake revenge porn sector over the past several years.

In 2018, fewer than 2,000 videos had been uploaded to the best-known deepfake streaming site; by last year, that number had ballooned to 13,000, with a monthly view count of 16 million.

As deepfake revenge porn becomes more popular, the barrier to access is quite low: The app that misused Watson’s face in its ads charges just US$8 per week.

The rapid increase in the number and availability of nonconsensual deepfake porn videos raises alarming questions about privacy and consent in the digital future. How will the huge number of women — and the smaller, but significant, number of men — who are impacted by this new AI-enabled revenge porn manage their reputations and lives? As the technology improves, how will viewers know the difference between fact and AI-generated fiction? How can nonconsensual material be removed when the Internet moves so much faster than regulation?

The example of these apps — and of the men, like Ewing and his fans, who use them — also illuminates something older, and more uncomfortable, about the nature of porn: that men often use it as an expression of their contempt for women, and feel that the sexual depiction of women degrades and violates them.

This is, in fact, much of mainstream porn’s appeal, at least according to the sentiments of many men who consume it: that it enables men to imagine themselves in control of women, and of inflicting pain and degradation on them.

Deepfake revenge porn, then, merely fulfills with technology what mainstream porn has offered men in fantasy: the assurance that any woman can be made lesser, degraded and humiliated, through sexual force. The nonconsent is the point; the humiliation is the point; the cruelty is the point.

There is no other way to understand deepfake pornography’s appeal. It is not as if the Internet lacks sexual content depicting real and consenting adults. What these apps offer their users is specifically and explicitly the opportunity to hurt women by forcing them into pornography against their will.

After Ewing exposed his deepfake pornography to his streaming audience in January, one of the women depicted issued her own tearful video, describing how the malice and violation of the deepfake had wounded her.

In response, a man sent her a picture of her own crying face appearing on his tablet . The screen was covered in semen.

For now, the women and others who are targeted by deepfake revenge porn have few avenues of legal recourse. Most US states have laws punishing revenge porn, but only four — California, New York, Georgia and Virginia — ban nonconsensual deepfakes. Companies hosting the apps are often based overseas, mostly beyond the reach of legal enforcement; the company whose app was advertised on Meta appears to be owned by a parent company based in China.

Meanwhile, more men will begin to use the technology against more women.

“I was on fucking Pornhub and there was an ad” for the deepfake site, Ewing said in his apology video, by way of explaining how he discovered the AI revenge porn site. “There’s an ad on every fucking video for this so I know other people must be clicking it.”

The conflict in the Middle East has been disrupting financial markets, raising concerns about rising inflationary pressures and global economic growth. One market that some investors are particularly worried about has not been heavily covered in the news: the private credit market. Even before the joint US-Israeli attacks on Iran on Feb. 28, global capital markets had faced growing structural pressure — the deteriorating funding conditions in the private credit market. The private credit market is where companies borrow funds directly from nonbank financial institutions such as asset management companies, insurance companies and private lending platforms. Its popularity has risen since

The Donald Trump administration’s approach to China broadly, and to cross-Strait relations in particular, remains a conundrum. The 2025 US National Security Strategy prioritized the defense of Taiwan in a way that surprised some observers of the Trump administration: “Deterring a conflict over Taiwan, ideally by preserving military overmatch, is a priority.” Two months later, Taiwan went entirely unmentioned in the US National Defense Strategy, as did military overmatch vis-a-vis China, giving renewed cause for concern. How to interpret these varying statements remains an open question. In both documents, the Indo-Pacific is listed as a second priority behind homeland defense and

Every analyst watching Iran’s succession crisis is asking who would replace supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Yet, the real question is whether China has learned enough from the Persian Gulf to survive a war over Taiwan. Beijing purchases roughly 90 percent of Iran’s exported crude — some 1.61 million barrels per day last year — and holds a US$400 billion, 25-year cooperation agreement binding it to Tehran’s stability. However, this is not simply the story of a patron protecting an investment. China has spent years engineering a sanctions-evasion architecture that was never really about Iran — it was about Taiwan. The

After “Operation Absolute Resolve” to capture former Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro, the US joined Israel on Saturday last week in launching “Operation Epic Fury” to remove Iranian supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and his theocratic regime leadership team. The two blitzes are widely believed to be a prelude to US President Donald Trump changing the geopolitical landscape in the Indo-Pacific region, targeting China’s rise. In the National Security Strategic report released in December last year, the Trump administration made it clear that the US would focus on “restoring American pre-eminence in the Western hemisphere,” and “competing with China economically and militarily