Two weeks ago, the US Supreme Court decided that it would hear Gonzalez v Google, a landmark case that is giving certain social-media moguls sleepless nights for the very good reason that it could blow a large hole in their fabulously lucrative business models. Since this might be good news for democracy, it is also a reason for the rest of us to sit up and pay attention.

First, some background. In 1996, then-US representative Chris Cox and US Senator Ron Wyden inserted a clause into the sprawling telecommunications bill that was then on its way through the US Congress.

The clause eventually became Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act and read: “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.”

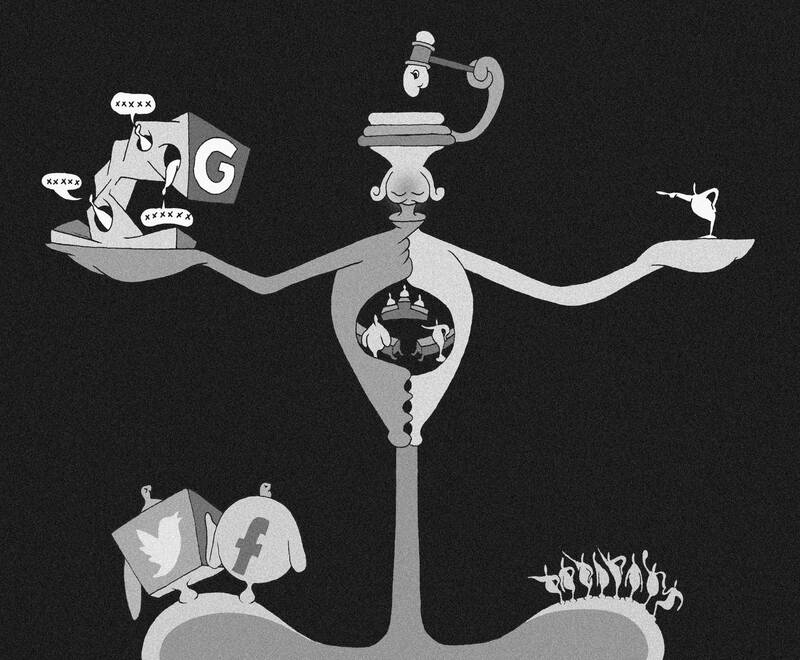

Illustration: Mountain People

The motives of the two politicians were honorable: They had seen how providers of early Web-hosting services had been held liable for damage caused by content posted by users over whom they had no control.

It is worth remembering that those were early days for the Internet, and Cox and Wyden feared that if lawyers had henceforth to crawl over everything hosted on the medium, then the growth of a powerful new technology would be crippled more or less from birth. In that sense they were right.

However, what they could not have foreseen was that Section 230 would turn into a get-out-of-jail card for some of the most profitable companies on the planet — such as Google, Facebook and Twitter, which built platforms enabling their users to publish anything and everything without the owners incurring legal liability for it.

So far-reaching was the Cox-Wyden clause that a law professor eventually wrote a whole book about it, The Twenty-Six Words That Created the Internet. A bit hyperbolic, perhaps, but you get the idea.

Now spool forward to November 2015 when Nohemi Gonzalez, a young American studying in Paris, was gunned down in a restaurant by Islamic State (IS) terrorists who murdered 129 other people that night. Her family sued Google, arguing that its YouTube subsidiary had used algorithms to push Islamic State videos to impressionable viewers, using the information that the company had collected about them.

Their petition seeking a US Supreme court review argues that “videos that users viewed on YouTube were the central manner in which IS enlisted support and recruits from areas outside the portions of Syria and Iraq which it controlled.”

However, the key thing about the Gonzalez suit is not that YouTube should not be hosting Islamic State videos (Section 230 allows that), but that its machine-learning “recommendation” algorithms, which might push other, perhaps more radicalizing, videos, renders it liable for the resulting damage. Or, to put it crudely, while YouTube might have legal protection for hosting whatever its users post on it, it does not — and should not — have protection for an algorithm that determines what they should view next.

This is dynamite for the social-media platforms because recommendation engines are the key to their prosperity. They are the power tools that increase the user “engagement” — keeping people on the platform to leave the digital trails (viewing, sharing, liking, retweeting, purchasing, etc) — that enable the companies to continually refine user profiles for targeted advertising — and make unconscionable profits from doing so.

If the US Supreme Court were to decide that these engines did not enjoy Section 230 protection, then social-media firms would suddenly find the world a much colder place. And stock-market analysts might be changing their advice to clients from “hold” to “sell.”

Legal academics have been arguing for decades that Section 230 needs revision. Freedom of speech fanatics see it as a keystone of liberty, as the “kill switch” of the Web. Former US president Donald Trump made threatening noises about it. Tech critics (such as this columnist) regard it as an enabler of corporate hypocrisy and irresponsibility.

However you look at it, though, it is more than a quarter of a century since it became law, which is about 350 years in Internet time. Having such a statute to regulate the contemporary networked world seems a bit like having a man with a red flag walking in front of a driverless vehicle. (Though, come to think of it, that might not be such a bad idea.)

Versions of the question posed by the Gonzalez suit — whether Section 230 immunizes Internet platforms when they make targeted recommendations of content posted by other users — have been put to US courts over the past few years.

To date, five US courts of appeals judges have concluded that the section does provide such immunity. Three appeals judges have ruled that it does not, while one other has concluded only that legal precedent precludes liability for recommendation engines.

In other words, there is no legal consensus here. It is high time that the Supreme Court decided the matter. After all, is it not what it is there for?

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has long been expansionist and contemptuous of international law. Under Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平), the CCP regime has become more despotic, coercive and punitive. As part of its strategy to annex Taiwan, Beijing has sought to erase the island democracy’s international identity by bribing countries to sever diplomatic ties with Taipei. One by one, China has peeled away Taiwan’s remaining diplomatic partners, leaving just 12 countries (mostly small developing states) and the Vatican recognizing Taiwan as a sovereign nation. Taiwan’s formal international space has shrunk dramatically. Yet even as Beijing has scored diplomatic successes, its overreach

After more than a year of review, the National Security Bureau on Monday said it has completed a sweeping declassification of political archives from the Martial Law period, transferring the full collection to the National Archives Administration under the National Development Council. The move marks another significant step in Taiwan’s long journey toward transitional justice. The newly opened files span the architecture of authoritarian control: internal security and loyalty investigations, intelligence and counterintelligence operations, exit and entry controls, overseas surveillance of Taiwan independence activists, and case materials related to sedition and rebellion charges. For academics of Taiwan’s White Terror era —

On Feb. 7, the New York Times ran a column by Nicholas Kristof (“What if the valedictorians were America’s cool kids?”) that blindly and lavishly praised education in Taiwan and in Asia more broadly. We are used to this kind of Orientalist admiration for what is, at the end of the day, paradoxically very Anglo-centered. They could have praised Europeans for valuing education, too, but one rarely sees an American praising Europe, right? It immediately made me think of something I have observed. If Taiwanese education looks so wonderful through the eyes of the archetypal expat, gazing from an ivory tower, how

After 37 US lawmakers wrote to express concern over legislators’ stalling of critical budgets, Legislative Speaker Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜) pledged to make the Executive Yuan’s proposed NT$1.25 trillion (US$39.7 billion) special defense budget a top priority for legislative review. On Tuesday, it was finally listed on the legislator’s plenary agenda for Friday next week. The special defense budget was proposed by President William Lai’s (賴清德) administration in November last year to enhance the nation’s defense capabilities against external threats from China. However, the legislature, dominated by the opposition Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), repeatedly blocked its review. The