As Ethiopia begins diverting 13.5 billion cubic meters of water from the Blue Nile River to its controversial new mega-dam, residents of Sudan to the south fear a repetition of last year’s devastating drought.

The second stage of filling the US$4.5 billion reservoir is ratcheting up tensions between Ethiopia and neighbors Sudan and Egypt, who depend on the Nile to support farming and generate power for their economies.

It is also altering decades of behavior by the river, which normally swells in July when seasonal rains come. It affects tens of millions of people living along the 6,650km-long Nile who rely on it for their water supply.

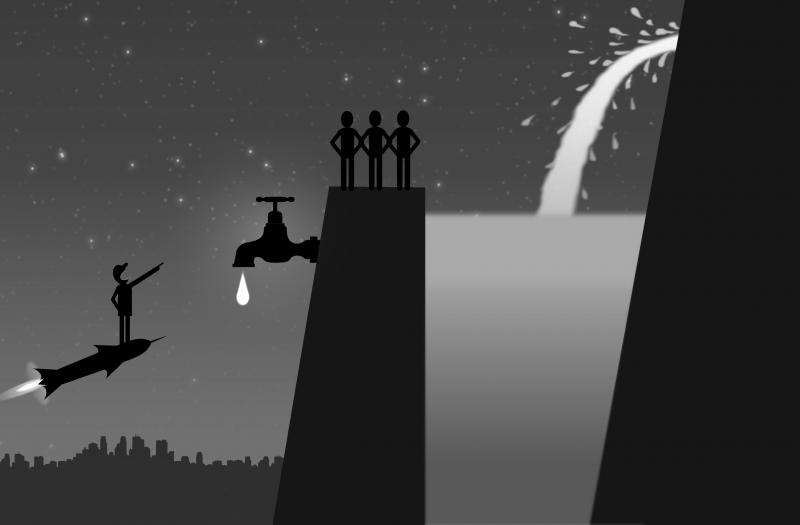

Illustration: Yusha

The move by Ethiopia to tap enough water to fill 5.4 million Olympic-size swimming pools was telegraphed for months. Yet it highlights how the many rounds of attempted mediation with Sudan and Egypt have failed, raising questions as to whether a solution can ever be found, or if Ethiopia will simply win by getting the dam filled in the meantime.

It also comes at a delicate time for the administration of Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, who has a strong incentive to push ahead with the project and make good on his promises to rejuvenate an economy that is set to grow at a tepid 2 percent this year. While Abiy’s party leads the vote count in last month’s parliamentary elections, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate’s popularity has dropped from the levels he enjoyed when he first took office in 2018.

Meanwhile, his military has been embroiled in fighting in the northern breakaway region of Tigray for the past eight months, and his troops have also clashed with Sudanese soldiers in a disputed border region that contains a much-coveted fertile stretch of land.

None of the parties in the wrangling over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) want the dispute to set off a broader war, but the more the dam becomes a reality, the greater the risk is that it bleeds into pre-existing military frictions.

For Amal Hassen and her family in the town of Roseires in Sudan, about 60km downriver from the Ethiopian border, the loss of water supply to their home last year was a clear signal that the dam project, with its 6,000-megawatt hydropower plant, spells disaster. She had to walk more than 1.6km to collect water in jerry cans from the river bank. Drinking that untreated water made her family sick.

“We tried to add chlorine to the river water so we could drink,” Hassen said at her home. “Every day, I would help the community to boil water.”

Ethiopia, Africa’s second-most populous nation, says the dam is needed to address chronic energy shortages and sustain its manufacturing industries; Sudan says filling the reservoir could hinder the southerly flow of water it requires to sustain its own electricity production and agriculture; and Egypt objects to a dam on a river that is the sole source of fresh water for as many as 100 million of its people.

As Abiy’s government moves ahead with the next stage of filling the dam, a diplomatic solution still looks elusive. That is despite many rounds of talks over a period of a decade, and the attempted mediation by the African Union. There have also been attempts to rope in the US, the UN and the EU to help navigate an agreement.

Egyptian Minister of Foreign Affairs Sameh Shoukry, in New York for a UN Security Council meeting on the issue last week, said that both his country and Sudan are committed to talks and a peaceful settlement.

Even so, “all options are on the table” when it comes to reaching that goal, he said in an interview with the pan-Arab satellite channel Arabiya.

Egypt has suggested that the dam be filled over a period of as long as 15 years, and it is pressing for guarantees that water will be released during times of drought.

The repercussion of the failure to conclude a treaty became evident on July 13 last year, when the dam gates were closed as heavy rains pounded the Ethiopian highlands and 5 billion cubic meters of water were collected in its reservoir. No warning was given to the Sudanese, who operate a much smaller dam of their own downstream in Roseires.

A monitoring station located at the border between Ethiopia and Sudan showed the Nile’s water level plummeted 100 million cubic meters between July 12 and 13, Sudanese government logs show. The last time they dropped that low was in 1984, the driest year on record.

Further downstream, six drinking water stations for the Sudanese capital, Khartoum, ran dry, leaving most of the city’s 5 million people without piped supplies for three days. Irrigation systems along the Nile’s banks stopped working, damaging crops.

Ethiopia’s unilateral actions prevented the Sudanese from adjusting water levels at the Roseires dam and a smaller reservoir on the White Nile River to compensate for the filling of the GERD, according to a Sudanese government document seen by Bloomberg.

Government officials, residents along the Blue Nile’s banks and hydrological experts interviewed by Bloomberg gave the same account of how the filling unfolded.

Ethiopian Minister of Water, Energy, Irrigation and Electricity Seleshi Bekele did not reply to questions.

He has stated publicly that there is a conspiracy to thwart Ethiopia’s sovereign right to fill the dam. He has also said water flows to Sudan and Egypt will never be interrupted, and filling the dam will reduce the risk of flooding in Sudan and the amount of sediment flowing downstream.

Flooding has been a perennial problem in the region. In August last year, hundreds of homes, an untold quantity of crops and entire sections of road were destroyed in Sudan’s Blue Nile, Sinnar and Al-Jazeera states after heavy rains fell over Ethiopia after a long drought.

Government contractors are still busy repairing the road and bridges between Khartoum and Roseires, while homes close to the Blue Nile’s banks are still being rebuilt.

Mustafa Hussein, the head of Sudan’s technical negotiating team on the dam, said Ethiopia could have minimized damage by gradually filling the GERD in August when the rainfall is heaviest, rather than retaining 5 billion cubic meters within a week in July.

Flooding and drought are not the only issues. In November last year, Ethiopia opened one of the GERD’s lower gates for 42 minutes, releasing 3 million cubic meters of water, according to a description of the event recounted in a letter Seleshi wrote to his Sudanese counterpart.

Minutes later, Sudan’s El Deim monitoring station, located just over the Ethiopian border, recorded a sudden rise in sediment flowing downstream. The heavy silt blocked four of the Roseires dam’s seven turbines, causing power outages that stretched as far as Khartoum, said its manager, Abdullah Ahmed.

While experts say Sudan is better prepared for this year’s filling of the GERD, and plans to retain more water in the Roseires dam to avoid a drought, there is little it can do to prepare for another flushing of sediment.

Water shortages remain Hassen’s main concern.

“We will not be happy if it happens again,” she said. “We pray the government protects us this year.”

After more than a year of review, the National Security Bureau on Monday said it has completed a sweeping declassification of political archives from the Martial Law period, transferring the full collection to the National Archives Administration under the National Development Council. The move marks another significant step in Taiwan’s long journey toward transitional justice. The newly opened files span the architecture of authoritarian control: internal security and loyalty investigations, intelligence and counterintelligence operations, exit and entry controls, overseas surveillance of Taiwan independence activists, and case materials related to sedition and rebellion charges. For academics of Taiwan’s White Terror era —

On Feb. 7, the New York Times ran a column by Nicholas Kristof (“What if the valedictorians were America’s cool kids?”) that blindly and lavishly praised education in Taiwan and in Asia more broadly. We are used to this kind of Orientalist admiration for what is, at the end of the day, paradoxically very Anglo-centered. They could have praised Europeans for valuing education, too, but one rarely sees an American praising Europe, right? It immediately made me think of something I have observed. If Taiwanese education looks so wonderful through the eyes of the archetypal expat, gazing from an ivory tower, how

After 37 US lawmakers wrote to express concern over legislators’ stalling of critical budgets, Legislative Speaker Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜) pledged to make the Executive Yuan’s proposed NT$1.25 trillion (US$39.7 billion) special defense budget a top priority for legislative review. On Tuesday, it was finally listed on the legislator’s plenary agenda for Friday next week. The special defense budget was proposed by President William Lai’s (賴清德) administration in November last year to enhance the nation’s defense capabilities against external threats from China. However, the legislature, dominated by the opposition Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), repeatedly blocked its review. The

China has apparently emerged as one of the clearest and most predictable beneficiaries of US President Donald Trump’s “America First” and “Make America Great Again” approach. Many countries are scrambling to defend their interests and reputation regarding an increasingly unpredictable and self-seeking US. There is a growing consensus among foreign policy pundits that the world has already entered the beginning of the end of Pax Americana, the US-led international order. Consequently, a number of countries are reversing their foreign policy preferences. The result has been an accelerating turn toward China as an alternative economic partner, with Beijing hosting Western leaders, albeit