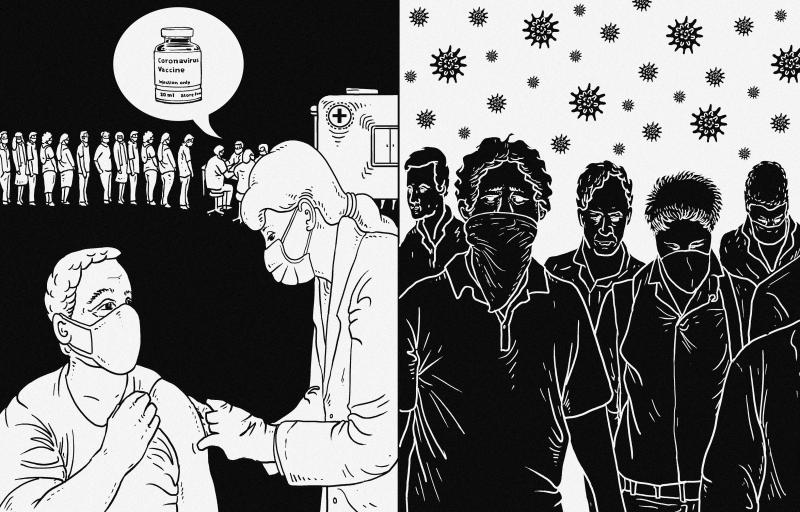

A chorus of vaccine advocates are calling for changes to intellectual property laws in hopes of beginning to boost COVID-19 vaccine manufacturing globally, and addressing the gaping disparity between rich and poor nations’ access to the vaccines.

The US and a handful of other wealthy, vaccine-producing nations are on track to deliver vaccines to all adults who want them in the coming months, while dozens of the world’s poorest countries have not inoculated a single person.

Some advocates have dubbed the disparity a “vaccine apartheid” and called for the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies to share technical know-how in an effort to speed up the global vaccination project.

Illustration: Mountain People

“The goal of health agencies right now is to manage the pandemic, and that might mean not everyone getting access — and not just this year — in the long-term,” Public Citizen’s access to medicine program director Peter Maybarduk said. “If we want to change that, if we’re not going to wait until 2024, then it requires more ambitious and a different scale of mobilization of resources.”

At the moment, “it’s not even clear the goal is to vaccinate the world,” Maybarduk added.

The pressure to get more vaccines to poor nations has also weighed on the administration of US President Joe Biden, which is now considering whether to repurpose or internationally distribute 70 million vaccine doses.

After outcry, the US has shared 4 million doses of the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine with Canada and Mexico.

“There’s no question poorer countries are having a hard time affording doses,” said Howard Markel, a pandemic historian at the University of Michigan School of Public Health. “Even if they were at wholesale or cost there are a lot of different markups.”

As it stands, 30 countries have not received a single vaccine dose.

About 90 million doses expected to be distributed through COVAX, a global alliance to allocate vaccines to poor countries, have been delayed through last month and this month due to a COVID-19 outbreak in India.

In Europe, rising cases and a slow vaccination campaign have also prompted vaccine export controls.

Beyond existing vaccine supply, many advocates see a bigger fight in patent laws, drawing on experience advocating for greater access to antiretroviral drugs for HIV.

“More is possible than we believe,” Maybarduk said. “It was assumed AIDS drugs could not be produced for less than 10,000 US dollars per person per year, right up until the moment they could, and they were produced for one dollar per person per day.”

Similarly, Maybarduk said that the technology for COVID-19 vaccines, along with other supplies, should be shared among the countries of the world.

Advocates have used Moderna as a key example of the leverage the US government might have, if it chose to use it.

Although popular shorthand often refers to it as just the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine, it was developed in partnership with the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease.

US taxpayers provided US$6 billion in late-stage development funds, in return for potential vaccine doses.

It was also tested on Americans, who volunteered for research across 99 sites.

“It is literally the people’s vaccine,” Maybarduk said.

A proposal from advocates focuses on a petition to temporarily suspend intellectual property laws governing WTO member states. Suspending those laws could urge companies to share technology, and better protect the whole world from emerging COVID-19 variants that can blunt vaccine efficacy, advocates say.

“This is a classic case where you have an industry that has a very direct stake in protecting itself, and there’s very little understanding among the public how much is at issue,” said Dean Baker, an economist and cofounder of the Center for Economic and Policy Research.

Advocates argue that pharmaceutical companies should share production know-how and be appropriately compensated.

One part of this fight centers on a provision of international trade law called the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS).

Put in force in 1995, the agreement requires all member states to recognize 20-year monopoly patents for pharmaceuticals, including vaccines.

“What TRIPS was about was imposing US-European style copyright on the whole world,” Baker said. “Most developing countries had very little idea what they were dealing with.”

In October last year, South Africa and India introduced a petition to suspend the agreement through the COVID-19 pandemic.

India is home to one of the largest generic drug manufacturing industries in the world. South Africa has the largest HIV epidemic in the world, and is part of a group of sub-Saharan African countries which were priced out of antiretroviral therapies in the 1990s.

“Even if we say: ‘OK, this is highly specialized knowledge,’” Baker said. “The idea it wouldn’t benefit everyone to share that knowledge is kind of crazy. The industry’s argument — ‘we’re just stuck’ — that makes zero sense.”

However, some vaccine researchers counter that the lack of vaccine access is far more complicated than lifting patent restrictions, because there is so little manufacturing outside of the US and Europe.

“In my experience from working on vaccines for the last few decades, the patents are not the biggest problem, the intellectual property is not the biggest problem,” said Peter Hotez, a vaccine researcher and dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Texas.

Hotez is working to develop a low-cost, easily manufactured COVID-19 vaccine that can be distributed in low and middle-income countries.

“The problem with vaccines is having the infrastructure and the human capital to know how to make vaccines,” Hotez said.

Reliance on major pharmaceutical companies has resulted in a dearth of vaccine candidates designed for regional COVID-19 variants and suited for local administration, he said.

“We’ve still not fixed a broken financial model for how to get vaccines for the poor,” Hotez said.

On this, both camps agree.

“There should be major facilities in Africa and Asia and Latin America, as well as North America, that help respond to future pandemics,” Maybarduk said. “What is not agreed on is what the political economy of that looks like: Who controls those facilities, will the technology be openly available, will they be publicly accountable?”

The fight also comes at a time when annual or booster COVID-19 shots appear increasingly likely — in part driven by the possibility that variants could emerge in populations without vaccine access — and as pharmaceutical companies eye future profits .

“The big players are AstraZeneca, Moderna, BioNtech — these are not really vaccine companies,” Hotez said.

They are involved because technological advances would “provide a glidepath so they can accelerate their technology to down the line make actual money making products,” such as vaccines to treat cancer and neurodegenerative disorders, he said.

The TRIPS agreement is expected to be discussed again later this month, although it is unclear whether the coalition of more than 80 poorer nations would succeed.

Opposition to the TRIPS petition has come from wealthy countries, including the US, which for the past four decades has traditionally argued for enhanced patent protections.

It is unclear how US Trade Representative Katherine Tai (戴琪) might handle the talks.

“Here you’ve got the equivalent of a blockbuster vaccine, because everybody needs it,” Markel said. “If you need it every year, boy, what a boon.”

Donald Trump’s return to the White House has offered Taiwan a paradoxical mix of reassurance and risk. Trump’s visceral hostility toward China could reinforce deterrence in the Taiwan Strait. Yet his disdain for alliances and penchant for transactional bargaining threaten to erode what Taiwan needs most: a reliable US commitment. Taiwan’s security depends less on US power than on US reliability, but Trump is undermining the latter. Deterrence without credibility is a hollow shield. Trump’s China policy in his second term has oscillated wildly between confrontation and conciliation. One day, he threatens Beijing with “massive” tariffs and calls China America’s “greatest geopolitical

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairwoman Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) made the astonishing assertion during an interview with Germany’s Deutsche Welle, published on Friday last week, that Russian President Vladimir Putin is not a dictator. She also essentially absolved Putin of blame for initiating the war in Ukraine. Commentators have since listed the reasons that Cheng’s assertion was not only absurd, but bordered on dangerous. Her claim is certainly absurd to the extent that there is no need to discuss the substance of it: It would be far more useful to assess what drove her to make the point and stick so

The central bank has launched a redesign of the New Taiwan dollar banknotes, prompting questions from Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators — “Are we not promoting digital payments? Why spend NT$5 billion on a redesign?” Many assume that cash will disappear in the digital age, but they forget that it represents the ultimate trust in the system. Banknotes do not become obsolete, they do not crash, they cannot be frozen and they leave no record of transactions. They remain the cleanest means of exchange in a free society. In a fully digitized world, every purchase, donation and action leaves behind data.

A large majority of Taiwanese favor strengthening national defense and oppose unification with China, according to the results of a survey by the Mainland Affairs Council (MAC). In the poll, 81.8 percent of respondents disagreed with Beijing’s claim that “there is only one China and Taiwan is part of China,” MAC Deputy Minister Liang Wen-chieh (梁文傑) told a news conference on Thursday last week, adding that about 75 percent supported the creation of a “T-Dome” air defense system. President William Lai (賴清德) referred to such a system in his Double Ten National Day address, saying it would integrate air defenses into a