As the UK’s COVID-19 vaccination program was “knocked off course” due to a delay in receiving 5 million doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine from India, a far more chilling reality was unfolding: About one-third of humanity, living in the poorest countries, found out that they would get almost no COVID-19 vaccines in the near future because of India’s urgent need to vaccinate its own massive population.

It is somewhat rich for figures in the UK to accuse India of vaccine nationalism. That the UK, which has vaccinated nearly 50 percent of its adults with at least one dose, should demand vaccines from India, which has only vaccinated 3 percent of its people, is immoral.

That the UK has already received several million doses from India, alongside other rich countries such as Saudi Arabia and Canada, is a travesty.

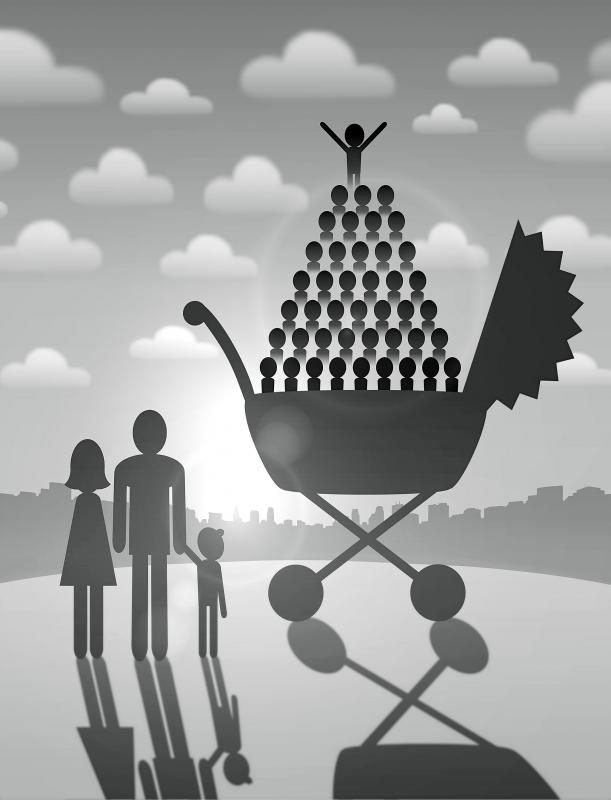

Illustration: Yusha

The billions of AstraZeneca doses produced by Serum Institute of India Ltd are not for rich countries — and, in fact, not even for India alone: They are for all 92 of the poorest countries in the world.

Except they are treated as the sovereign property of the Indian government.

How did we get here? Exactly one year ago, researchers at the University of Oxford’s Jenner Institute, then the frontrunners in the race to develop a COVID-19 vaccine, said that they intended to allow any manufacturer, anywhere, the rights to their jab.

One of the early licenses they signed was with the Serum Institute, the world’s largest vaccine manufacturer.

One month later, acting on advice from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the university changed course and signed over exclusive rights to AstraZeneca, a UK-based multinational pharmaceutical group.

AstraZeneca and the Serum Institute signed a new deal. The Indian firm would produce vaccines for all poor countries eligible for assistance by Gavi, the Vaccines Alliance, an organization backed by rich countries’ governments and the foundation.

The 92 eligible nations account for half the world population — or nearly 4 billion people.

India’s fair share of these vaccines, by population, should have been 35 percent. However, there was an unwritten arrangement that the Serum Institute would earmark 50 percent of its supply for domestic use and 50 percent for export.

The deal included a clause that allowed AstraZeneca to approve exports to countries not listed in the agreement.

Some countries that asked for emergency vaccine shipments from India, including South Africa and Brazil, were justified: They had nothing else.

However, rich countries like the UK and Canada, which had bought more doses than required to vaccinate their populations, to the detriment of everyone else, had no moral right to dip into a pool of vaccines designated for poor countries.

Paradoxically, when South Africa and India asked the WTO to temporarily waive patents and other pharmaceutical monopolies so that vaccines could be manufactured more widely to prevent shortfalls in supply, among the first countries to object were the UK, Canada and Brazil. They were the very governments that would later ask India to solve their own shortfalls in supply.

The deal did not include restrictions on what price the Serum Institute could charge, despite AstraZeneca’s pledge to sell its vaccine for no profit “during the COVID-19 pandemic,” which led to Uganda, which is among the poorest countries on Earth, paying three times more than Europe for the same vaccine.

An AstraZeneca spokesperson told US media company Politico that the “price of the vaccine will differ due to a number of factors, including the cost of manufacturing — which varies depending on the geographic region — and volumes requested by the countries.”

As it became clear that the Western pharmaceutical industry could barely supply the West, let alone anywhere else, many countries turned to Chinese and Russian vaccines.

Meanwhile, COVAX — a Gavi-backed initiative that does procure vaccines for poor countries — stuck to its guns and made deals exclusively with Western vaccine manufacturers.

From those deals, the AstraZeneca vaccine is now the only viable candidate it has. The bulk of the supply of this vaccine comes from the Serum Institute, and a smaller quantity from SK Bioscience Co in South Korea.

As a result, one-third of humanity is largely dependent on supplies of one vaccine from one company in India.

Cue the Indian government’s involvement. Unlike Western governments, which poured large amounts of money into the research and development of vaccines, there is no evidence that the Indian government has provided a rupee in research and development funding to the Serum Institute. (This did not stop it from turning every overseas vaccine delivery into a photo opportunity.)

New Delhi commandeered approval of every single COVAX shipment sent out from the Serum Institute — even directing how many doses would be sent and when, a well-placed source within the institute said.

The Indian government has not publicly commented on its involvement in the vaccine shipments and has refused requests for comment.

Last month, faced with a surge in COVID-19 infections, New Delhi announced an expansion of its domestic vaccination program to include 345 million people, and halted all exports of vaccines.

About 60 million vaccine doses have already been dispensed, and the Indian government needs another 630 million to cover everyone in this phase alone.

One other vaccine is approved for use — Bharat Biotech’s Covaxin — but it is produced and utilized in smaller quantities.

As more vaccines are approved, the pressure on the Serum Institute might decrease. However, for now, the bulk of India’s vaccination goals are to be met by just one supplier, which faces the impossible choice of either letting down the other 91 countries depending on it, or offending its own government.

The consequences are devastating. To date, 28 million COVAX doses have been produced by the Indian firm for the developing world — 10 million of which remained in India.

The second-largest bulk went to Nigeria, which received 4 million doses, enough to cover less than 2 percent of its population.

Given the new Indian government order of 100 million doses, further supplies to countries like Nigeria might be delayed until July, and, given the Indian government’s need of 500 million more doses in the short run, that date could surely be pushed out even further.

This colossal mess was entirely predictable, and could have been avoided at every turn.

Rich countries such as the UK, the US and those of the EU, and rich organizations such as COVAX should have used their funding of Western pharmaceutical companies to nip vaccine monopolies in the bud.

The University of Oxford should have stuck to its plans of allowing anyone, anywhere, to make its vaccine. AstraZeneca and COVAX should have licensed as many manufacturers in as many countries as they could to make enough vaccines for the world.

The Indian government should have never been effectively put in charge of the well-being of every poor country on the planet.

For years, India has been called “the pharmacy of the developing world.” It is time to rethink that title. We will need many more pharmacies in many more countries to survive this pandemic.

Achal Prabhala is the coordinator of the AccessIBSA project, which campaigns for access to medicines in India, Brazil and South Africa. Leena Menghaney is an Indian lawyer who has worked on pharmaceutical law and policy for two decades.

As the new year dawns, Taiwan faces a range of external uncertainties that could impact the safety and prosperity of its people and reverberate in its politics. Here are a few key questions that could spill over into Taiwan in the year ahead. WILL THE AI BUBBLE POP? The global AI boom supported Taiwan’s significant economic expansion in 2025. Taiwan’s economy grew over 7 percent and set records for exports, imports, and trade surplus. There is a brewing debate among investors about whether the AI boom will carry forward into 2026. Skeptics warn that AI-led global equity markets are overvalued and overleveraged

An elderly mother and her daughter were found dead in Kaohsiung after having not been seen for several days, discovered only when a foul odor began to spread and drew neighbors’ attention. There have been many similar cases, but it is particularly troubling that some of the victims were excluded from the social welfare safety net because they did not meet eligibility criteria. According to media reports, the middle-aged daughter had sought help from the local borough warden. Although the warden did step in, many services were unavailable without out-of-pocket payments due to issues with eligibility, leaving the warden’s hands

Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi on Monday announced that she would dissolve parliament on Friday. Although the snap election on Feb. 8 might appear to be a domestic affair, it would have real implications for Taiwan and regional security. Whether the Takaichi-led coalition can advance a stronger security policy lies in not just gaining enough seats in parliament to pass legislation, but also in a public mandate to push forward reforms to upgrade the Japanese military. As one of Taiwan’s closest neighbors, a boost in Japan’s defense capabilities would serve as a strong deterrent to China in acting unilaterally in the

Taiwan last week finally reached a trade agreement with the US, reducing tariffs on Taiwanese goods to 15 percent, without stacking them on existing levies, from the 20 percent rate announced by US President Donald Trump’s administration in August last year. Taiwan also became the first country to secure most-favored-nation treatment for semiconductor and related suppliers under Section 232 of the US Trade Expansion Act. In return, Taiwanese chipmakers, electronics manufacturing service providers and other technology companies would invest US$250 billion in the US, while the government would provide credit guarantees of up to US$250 billion to support Taiwanese firms