May 26 to June 1

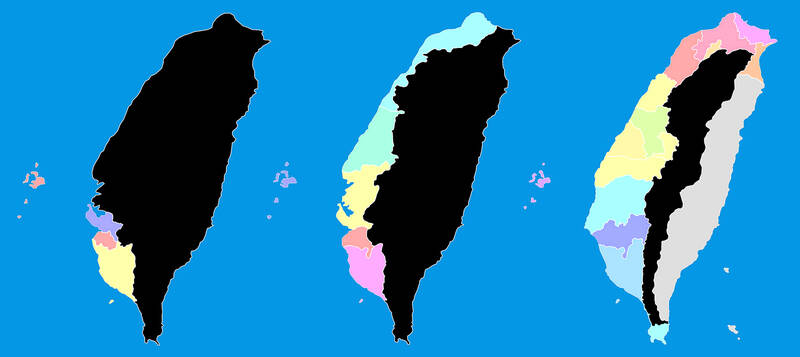

When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan.

But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with the administrative seat planned at today’s Taichung. However, due to various economic and geographic reasons, the capital ended up being moved to Taipei in 1894 — and has remained there since.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

After the Qing ceded Taiwan to the Japanese in 1895, much of central and eastern Taiwan were still controlled by Indigenous communities, and it would take the Japanese 20 more years to bring the entire island under its fold.

‘RECEIVING THE HEAVENS’

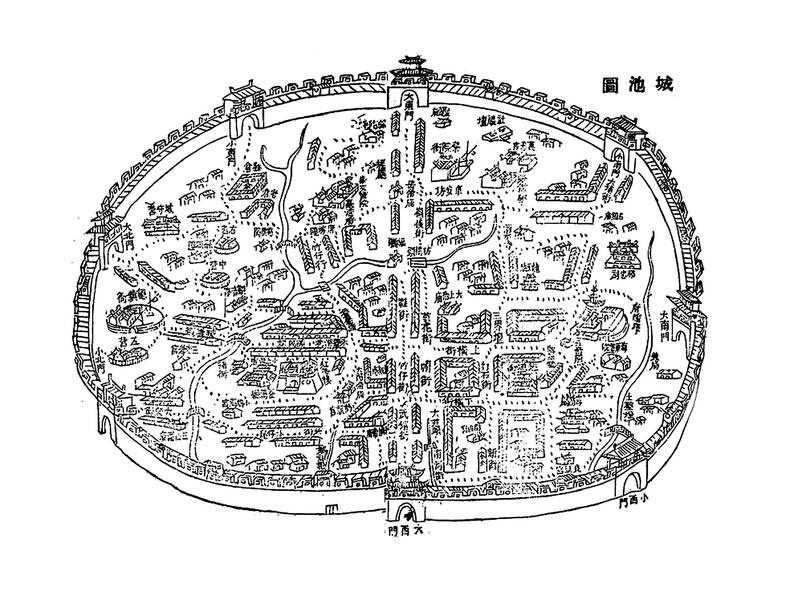

Established by Ming loyalist warlord Cheng Cheng-kung (鄭成功, also known as Koxinga), the Kingdom of Tungning (東寧), basically inherited the lands of the Dutch which they defeated in 1662. According to Changes in Taiwan’s Administrative Divisions (台灣的行政區變遷) by Shih Ya-hsuan (施雅軒), they renamed Fort Provintia “Chengtian Prefecture” (承天府, receiving the heavens), and to the north was Tianxing County (天興, heavenly prosperity) and to the south Wannian (萬年, ten-thousand years).

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The administrative institutions were located in Chengtian Prefecture. Cheng’s son Cheng Ching (鄭經) elevated the two counties to prefectures and added “pacification commissions” in lands bordering Indigenous territory as well as Penghu.

In 1683, Qing Dynasty admiral Shih Lang (施琅) destroyed the Kingdom of Tungning. The emperor and other officials had no interest in annexing Taiwan, one disparaging it as a “speck of dirt on the outer seas with naked, tattooed savages not worthy of spending our resources on.” Shih extolled Taiwan’s strategic location and abundant natural resources, adding that if left alone, pirates or other foreigners might occupy it and cause trouble for the Qing.

Shih may have had other motives (see “Taiwan in Time: The admiral’s secret plan,” Sept. 23, 2018), but in 1684, Taiwan officially became part of the Qing Empire.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

REBELLIONS AND UNREST

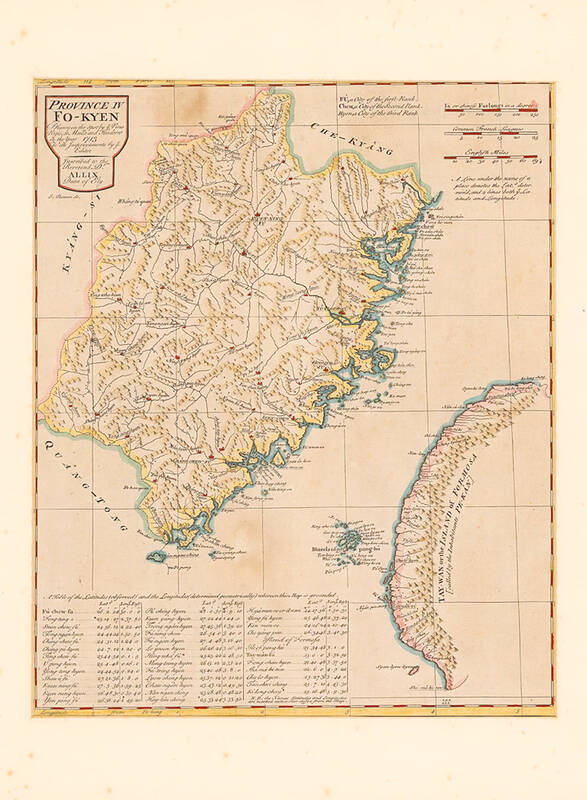

On May 27, 1684, the Qing designated the island as Taiwan Prefecture under Fujian Province. Chengtian Prefecture was renamed Taiwan County and remained the administrative seat, Tianxing was renamed Chuluo (諸羅) after a local Indigenous settlement and Wannian became Fengshan (鳳山). Chuluo nominally controlled a large swath of land, stretching from the today’s Yanshui River (鹽水溪) in Tainan all the way up the west coast to Keelung.

Officials were sent to Taiwan on three-year terms, and were not allowed to bring their families. It was the same with soldiers. The construction of stone fortifications was banned, in fear that rebels or remaining Ming loyalists might use them as bases. As a result, early cities were guarded with bamboo walls; this would change after the Lin Shuang-wen Rebellion (林爽文事件) of 1788.

This setup remained in place for the next 40 years, until “Duck King” Chu Yi-kuei (朱一貴) rose up against the Qing in April 1721. The unrest was quelled within two months, but this alarmed Qing officials who began discussing how to tighten security.

Officials such as Lan Ting-yuan (藍鼎元) and Wu Ta-li (吳達禮) urged the emperor to establish a new county north of the Huwei River (虎尾溪) as the Han population was growing and expanding fast. The result was Changhua County (彰化), but because the land was still too vast, Tamsui Subprefecture (淡水) was established to maintain order in the north. Curiously, the Tamsui officials still worked out of Changhua, only moving north to Hsinchu a few decades later. Around the same time, Penghu was also made a subprefecture.

Borders demarcating Han and Indigenous territories were also set up as Han settlers had seized most of the arable lowland of the west coast. They now turned their sights to the eastern mountains, leading to countless violent clashes. The government first put up stone steles, but this did not deter Han encroachment, and finally they began digging border ditches and stationing armed guards.

FOREIGN INVASIONS

After local militias helped quell the Lin Shuang-wen rebellion, the government renamed Chuluo to Chiayi (嘉義), which means “commending the righteous people.”

In 1796, Wu Sha (吳沙) managed to overpower Indigenous resistance and enter today’s Yilan; scores of Han settlers followed. This area was not under Qing jurisdiction. In 1806, the pirate Tsai Chien (蔡牽) attack Wushih Harbor (烏石港), but he was kept at bay with the help of these settlers. They also helped the Qing repulse the pirate Chu Fen (朱濆).

Over the years, they petitioned the government to set up an administrative unit in Yilan, stating that it could help better assert their maritime borders when pirate attacks were common. In 1812, Gemalan (Kavalan) Subprefecture was established.

The Mudan Incident (牡丹社事件) in 1874 (see “Paiwan reclaim a bloody past,” July 23, 2022) sparked a Japanese punitive expedition to Taiwan, which finally made the Qing realize Taiwan’s strategic importance. Taipei Prefecture was established to better control the north, and the Qing began actively pushing into Indigenous areas.

SEPARATE PROVINCE

Calls for Taiwan to become its own province had fallen on deaf ears for decades, but after the French invaded in 1884 as part of the Sino-French War, the Qing court finally agreed.

A new administration plan was drawn up, dividing Taiwan into three prefectures. The original Taiwan Prefecture was renamed Tainan, and a new Taiwan Prefecture was drawn up in central Taiwan intending to become the new provincial administrative center. Taipei Prefecture covered Taipei, Keelung, Yilan and Hsinchu.

Liu Ming-chuan (劉銘傳) found the planned site for the capital geographically suitable, but it was not close to water sources, making it difficult to transport materials to build new offices, writes Chuang Chi-fa (莊吉發) in “Examining adjustments in Taiwan’s Qing-era administrative regions from National Palace archives” (從故宮檔案看清代台灣行政區域調整). It was also sparsely populated with little commercial activity.

Liu’s priority was to finish building the north-south railroad to bring prosperity to the area first. But his successor, Shao Yu-lian (邵友濂) wanted to make Taipei the capital, citing similar issues. Taipei was already well-developed and had a railway that reached Hsinchu, and eventually Shao’s suggestion was accepted.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.

It’s a bold filmmaking choice to have a countdown clock on the screen for most of your movie. In the best-case scenario for a movie like Mercy, in which a Los Angeles detective has to prove his innocence to an artificial intelligence judge within said time limit, it heightens the tension. Who hasn’t gotten sweaty palms in, say, a Mission: Impossible movie when the bomb is ticking down and Tom Cruise still hasn’t cleared the building? Why not just extend it for the duration? Perhaps in a better movie it might have worked. Sadly in Mercy, it’s an ever-present reminder of just