From bombings and protests to the opening of a new health center, student journalist Baraa Razzouk has been documenting daily life in Idlib, Syria, for years, and posting the videos to his YouTube account.

Yet this month, the 21-year-old started getting automated e-mails from YouTube alerting him that his videos contravened its policy and would be deleted.

As of this month, more than a dozen of his videos had been removed, he said.

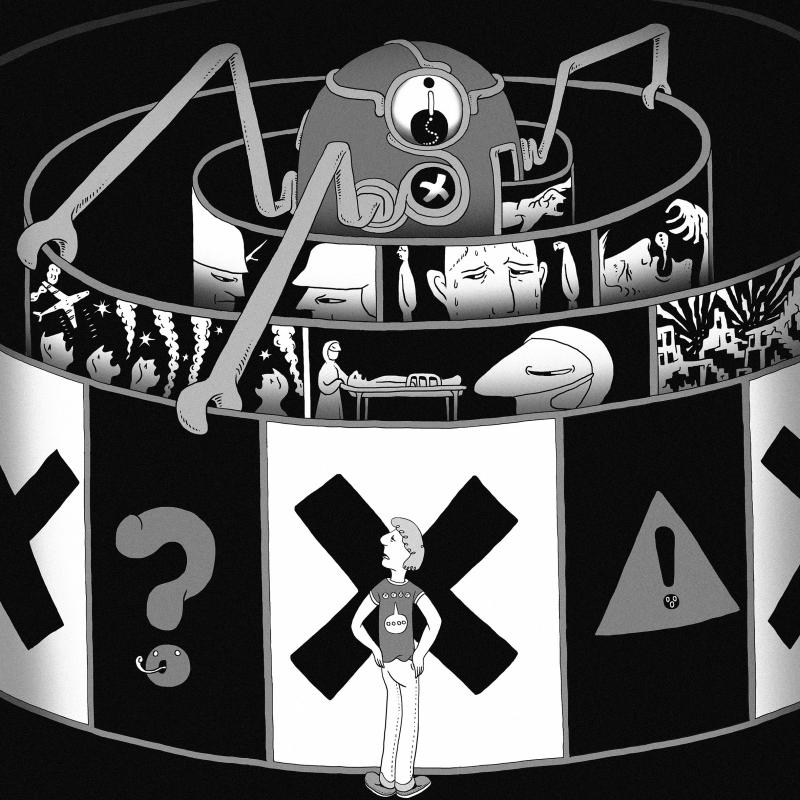

Illustration: Mountain People

“Documenting the [Syrian] protests in videos is really important — also, documenting attacks by regime forces,” he said in a telephone interview. “This is something I had documented for the world and now it’s deleted.”

YouTube, Facebook and Twitter in March said that videos and other content might be erroneously removed for policy contraventions, as the COVID-19 pandemic forced them to empty offices and rely on automated takedown software.

However, those artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled tools risk confusing human rights and historical documentation such as Razzouk’s videos with problematic material such as terrorist content — particularly in war-torn countries such as Syria and Yemen, digital rights activists have said.

“AI is notoriously context-blind,” said Jeff Deutch, a researcher for Syrian Archive, a nonprofit that archives video footage from conflict zones in the Middle East.

“It is often unable to gauge the historical, political or linguistic settings of posts ... human rights documentation and violent extremist proposals are too often indistinguishable,” he said in a telephone interview.

Erroneous takedowns threaten content such as videos that are used as formal evidence of rights violations by international bodies such as the International Criminal Court and the UN, said Dia Kayyali, program manager for tech and advocacy at digital rights group Witness.

“It’s a perfect storm,” Kayyali said.

After the Thomson Reuters Foundation flagged Razzouk’s account to YouTube, a spokesman said that the company had deleted the videos in error, although the removal was not appealed through their internal process.

YouTube has now restored 17 of Razzouk’s videos.

“With the massive volume of videos on our site, sometimes we make the wrong call,” the spokesman said in e-mailed comments. “When it’s brought to our attention that a video has been removed mistakenly, we act quickly to reinstate it.”

In the past few years, social media platforms have come under increased pressure from governments to quickly remove violent content and disinformation from their platforms, raising their reliance on AI systems.

With the help of automated software, YouTube removes millions of videos a year, and Facebook deleted more than 1 billion accounts last year for breaching rules such as not posting terrorist content.

Last year, social media companies pledged to block extremist content following a livestreamed terror attack on Facebook of a gunman killing 51 people at two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand.

Governments have followed suit, with French President Emmanuel Macron vowing to make France a leader in containing the spread of illicit content and false information on social media platforms.

However, the country’s top court this week rejected most of a draft law that would have compelled social media giants to remove any hateful content within 24 hours.

Firms such as Facebook have also pledged to remove misinformation about the novel coronavirus outbreak that could contribute to imminent physical harm.

These pressures, combined with an increased reliance on AI during the pandemic, puts human rights content in particular jeopardy, Kayyali said.

Social media firms typically do not disclose how frequently their AI tools mistakenly take down content, so the Syrian Archive group has been using its own data to approximate change over time in the rate of deletions of human rights documentation on crimes committed in Syria, which has been battered by nearly a decade of war.

The group flags accounts posting human rights content on social media platforms, and archives the posts on its servers. To approximate the rate of deletions they run a script pinging the original post each month to see if it has been removed.

“Our research suggests that since the beginning of the year, the rate of content takedowns of Syrian human rights documentations on YouTube roughly doubled” from 13 percent to 20 percent, Deutch said, calling the increase “unprecendented.”

Last month, Syrian Archive detected that more than 350,000 videos on YouTube had disappeared — up from 200,000 in May last year, including videos of aerial attacks, protests and destruction of civilians homes in Syria.

Deutch said that he had seen content takedowns in other war-torn countries in the region, including Yemen and Sudan.

“Users in conflict zones are more vulnerable,” he said.

Other groups, including Amnesty International and Witness, have warned of the trend elsewhere, including in sub-Saharan Africa.

Syrian Archive was not able to test for takedowns at Facebook, because outside researchers are restricted from the platform’s application programming interface, but earlier this month Syrians began using the hashtag “Facebook is fighting the Syrian revolution” to flag similar content takedowns on the platform.

Last month, Yahya Daoud, a Syrian humanitarian worker with the White Helmets emergency response group, shared a post and a photograph showing a woman who died in a 2012 massacre by the forces of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad in the Houla region.

By the end of the month, Daoud said that his account — which he had used since 2011 to document his life in Syria — was automatically deleted without explanation.

“I was depending on Facebook to be an archive for me,” he said.

“So many memories have been lost: the death of my friends, the day I became displaced, the death of my mother,” he said, adding that he had unsuccessfully tried to appeal the decision through Facebook’s automated complaints system.

Facebook did not respond to requests for comment.

Researchers say that they are only able to detect a small slice of erroneous content takedowns.

“We don’t know how many people are trying to speak and we aren’t hearing them,” said Alexa Koenig, executive director of the University of California Berkeley’s Human Rights Center.

“These algorithms are grabbing the content before we even see it,” said Koenig, whose center uses images and videos posted from conflict zones such as Syria to document human rights abuses and build cases.

YouTube said that 80 percent of videos flagged by its AI were deleted before anyone had seen them in the second quarter of last year.

Koenig worries that the erasure of these videos could jeopardize ongoing investigations around the world.

In 2017, the International Criminal Court issued its first arrest warrant that rested primarily on social media evidence, after video footage emerged on Facebook of Libyan National Army commander Mahmoud al-Werfalli.

The video purportedly showed him shooting dead 10 blindfolded prisoners at the site of a car bombing in Benghazi. He is still at large.

Koenig worries that this kind of documentation is now under threat.

“The danger is much higher than it was just a few months ago,” she said. “It’s a sickening feeling to know we aren’t close to where we need to be in preserving this content.”

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has long been expansionist and contemptuous of international law. Under Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平), the CCP regime has become more despotic, coercive and punitive. As part of its strategy to annex Taiwan, Beijing has sought to erase the island democracy’s international identity by bribing countries to sever diplomatic ties with Taipei. One by one, China has peeled away Taiwan’s remaining diplomatic partners, leaving just 12 countries (mostly small developing states) and the Vatican recognizing Taiwan as a sovereign nation. Taiwan’s formal international space has shrunk dramatically. Yet even as Beijing has scored diplomatic successes, its overreach

In her article in Foreign Affairs, “A Perfect Storm for Taiwan in 2026?,” Yun Sun (孫韻), director of the China program at the Stimson Center in Washington, said that the US has grown indifferent to Taiwan, contending that, since it has long been the fear of US intervention — and the Chinese People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) inability to prevail against US forces — that has deterred China from using force against Taiwan, this perceived indifference from the US could lead China to conclude that a window of opportunity for a Taiwan invasion has opened this year. Most notably, she observes that

For Taiwan, the ongoing US and Israeli strikes on Iranian targets are a warning signal: When a major power stretches the boundaries of self-defense, smaller states feel the tremors first. Taiwan’s security rests on two pillars: US deterrence and the credibility of international law. The first deters coercion from China. The second legitimizes Taiwan’s place in the international community. One is material. The other is moral. Both are indispensable. Under the UN Charter, force is lawful only in response to an armed attack or with UN Security Council authorization. Even pre-emptive self-defense — long debated — requires a demonstrably imminent

Since being re-elected, US President Donald Trump has consistently taken concrete action to counter China and to safeguard the interests of the US and other democratic nations. The attacks on Iran, the earlier capture of deposed of Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro and efforts to remove Chinese influence from the Panama Canal all demonstrate that, as tensions with Beijing intensify, Washington has adopted a hardline stance aimed at weakening its power. Iran and Venezuela are important allies and major oil suppliers of China, and the US has effectively decapitated both. The US has continuously strengthened its military presence in the Philippines. Japanese Prime