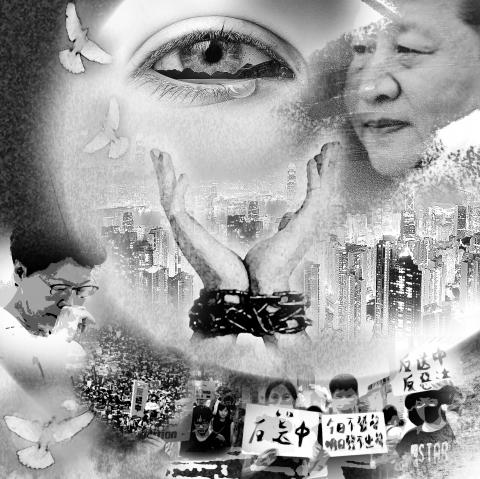

Why do the Hong Kong activists matter to us? Because their cause is universal. Aerial images of vast crowds flooding the streets of the skyscraper-studded territory are, of course, riveting. Equally fascinating is that, with China fast emerging as a global behemoth and surveillance state, this crisis serves as a barometer of what we might next expect of it and its president-cum-new-emperor, Xi Jinping (習近平).

There is also an astounding element of David versus Goliath in Hong Kong, something that awakens a deep instinct in us, a yearning to see bravery and determination in the face of great odds: Young people defying a giant and leveraging surprising tactics in their struggle.

As coincidence has it, this is all happening shortly after we have marked the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square Massacre, and rewatched the footage of that man singlehandedly stopping a column of tanks in June 1989 — an act of courage that remains a blockbuster. In Britain, there is of course particular interest in Hong Kong because of its colonial past, the 1997 handover and responsibilities attached to it. The question of whether China will renege on its commitment to “two systems” looms large.

Illustration: Kevin Sheu

However, something else is at work, something arguably more important than geopolitics, impressive TV pictures, heroic metaphors or what is left of one European country’s diplomatic clout.

It is this: Hong Kong offers up to us basic human aspirations that anyone, anywhere, can recognize and relate to.

When the activist Joshua Wong (黃之鋒) was released this week, his first words were about “fundamental rights and freedom.” He did not mention sovereignty, nor ethnicity, nor religious or cultural identity. As such, Hong Kong’s activists serve as a reminder of universal principles that we have become almost numb to in the age of suspicion, conspiracy theories, fake news, moral relativism and identity politics.

We have become accustomed to thinking about rights from the perspective of a specific group, whatever its characteristics; but here are rights being fought for in universal terms: “Fundamental” was the key word.

This points to what was enshrined in the international charters drawn up in the aftermath of World War II, when a global liberal order was tentatively put in place.

As the 1948 UN-adopted Universal Declaration of Human Rights puts it: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights,” and all are entitled to those rights and freedoms “without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.”

We are stunned by the images of Hong Kong not just because of the scale of these events or their historical dimension, but also because they somehow shake us out of a lethargy. Had we not become blase or cynical or fatalistic about the chances of defending human rights? Had we not started flirting with the notion that some principles might work fine for our Western world, but can hardly be considered as imperatives for others? Would that be because of our own imperfect record, our past empires, our “wars of choice,” our Western desolation in times of US President Donald Trump, Brexit, the far-right in Europe, arms sales to Saudi Arabia, you name it?

Or might it be because some of the nihilism on social media has blunted us?

Hong Kong is a brilliant, festive wake-up call, but with an attached worry: Can those young people prevail?

Take note also that for all our cringing about past experiences in regime change, the protests in Hong Kong have nothing to do with Western-fostered political pressure. They are not a CIA plot — however actively Chinese official propaganda might want to push that line — and they are certainly not the premise of a US-led military intervention.

Hong Kong rose up on its own. Just like Algerians did earlier this year. Just like the Sudanese protesters, crushed in Khartoum.

What does that tell us, if not that we in the West, or our governments, are hardly the puppet masters that some claim they are? In fact, when you think of it, is it not rather contemptuous, if not racist, to hold the knee-jerk belief that distant people only rise up when some kind of US neo-imperial plan is lurking in the background? And can we decently claim we risk “imposing” norms on others when — loud and clear on our screens — thousands are in fact seeking our attention and support?

Hong Kong rose up against an extradition law that threatens to place any citizen there at the mercy of China’s autocratic system. What the demonstrators have marched for is driven by homegrown aspirations, not some foreign-concocted challenge to the Chinese regime. What motivates Hong Kong’s population relates to basic human dignity — something that is borderless and found in each individual, not a product of Western encroachment.

Another thing is striking: In an era of rampant nationalism, Hong Kong stands out as the absolute anti-nationalist protest for essential, individual rights. How indeed could this possibly be a nationalistic movement, when the same nation lives on the island and on the mainland?

When you saw those images, perhaps you thought back to other momentous civil resistance struggles, born of local realities, but universalist in their message: Martin Luther King and the US civil rights movement, the eastern European 1989 revolutions that brought the Iron Curtain down and the anonymous heroes of the 2009 Green movement in Iran.

What I can not help thinking about is Syria, a place where the struggle for fundamental rights met a tragic fate: the dreams of those who in the spring of 2011 poured out on to the streets asking for the end of a 40-year dictatorship.

Hong Kong might seem far away from Syria, but the hopes of those people on the island are not much different from those of Syrian families who, for months, demonstrated peacefully each Friday with slogans such as: “We want freedom,” “Dignity” and “Your silence is killing us” — words addressed to us.

It is now commonplace to depict Syria as an ethnic conflict between communities at each other’s throats, and to be sure, that has sadly become part of the picture after eight long years of war.

However, in the early stages of the Syrian revolution, people stood up as one, no matter their origin or background, against a tyrant. Forgetting that very pertinent fact, or denying it, plays to this day into the hands of a regime that practices mass repression, ethnic cleansing and collective punishment — not unlike the Chinese authorities against some of its minorities.

Hong Kong is ethnically Chinese, but politically different from China — as is Taiwan. Against that backdrop, the events there do much to debunk the notion that cultural relativism can be an excuse to deprive people of fundamental rights.

This might seem obvious, but from Vladimir Putin’s Russia to Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi’s Egypt, and even in Europe with the likes of Viktor Orban in Hungary and Jarosaw Kaczyski in Poland dismantling the democratic rule of law, the argument is constantly made that “traditional values” or specific national contexts make it undesirable, or impossible, to abide by internationally agreed standards that protect individual rights.

If China’s rulers have their way in Hong Kong, there is little doubt that they will deploy that same line as a fig leaf for oppression.

Hong Kong’s activists stand for something vital for us all: the right of the individual not to be persecuted or extradited to a dictatorship, the right to assemble without incurring prison, the right to speak freely and to enjoy freedom of information. If we are truly internationalists or anti-nationalists, now is the time to embrace all those seemingly distant struggles as our own, and without distinction, without selective or variable indignation. Not because it suits our political agenda or our interests, but — yes — in human solidarity.

Universalism is not a dirty word, it is beautiful.

Natalie Nougayrede is a Guardian columnist.

There is much evidence that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is sending soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to support Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — and is learning lessons for a future war against Taiwan. Until now, the CCP has claimed that they have not sent PLA personnel to support Russian aggression. On 18 April, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelinskiy announced that the CCP is supplying war supplies such as gunpowder, artillery, and weapons subcomponents to Russia. When Zelinskiy announced on 9 April that the Ukrainian Army had captured two Chinese nationals fighting with Russians on the front line with details

Within Taiwan’s education system exists a long-standing and deep-rooted culture of falsification. In the past month, a large number of “ghost signatures” — signatures using the names of deceased people — appeared on recall petitions submitted by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) against Democratic Progressive Party legislators Rosalia Wu (吳思瑤) and Wu Pei-yi (吳沛憶). An investigation revealed a high degree of overlap between the deceased signatories and the KMT’s membership roster. It also showed that documents had been forged. However, that culture of cheating and fabrication did not just appear out of thin air — it is linked to the

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), joined by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), held a protest on Saturday on Ketagalan Boulevard in Taipei. They were essentially standing for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which is anxious about the mass recall campaign against KMT legislators. President William Lai (賴清德) said that if the opposition parties truly wanted to fight dictatorship, they should do so in Tiananmen Square — and at the very least, refrain from groveling to Chinese officials during their visits to China, alluding to meetings between KMT members and Chinese authorities. Now that China has been defined as a foreign hostile force,

On April 19, former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) gave a public speech, his first in about 17 years. During the address at the Ketagalan Institute in Taipei, Chen’s words were vague and his tone was sour. He said that democracy should not be used as an echo chamber for a single politician, that people must be tolerant of other views, that the president should not act as a dictator and that the judiciary should not get involved in politics. He then went on to say that others with different opinions should not be criticized as “XX fellow travelers,” in reference to