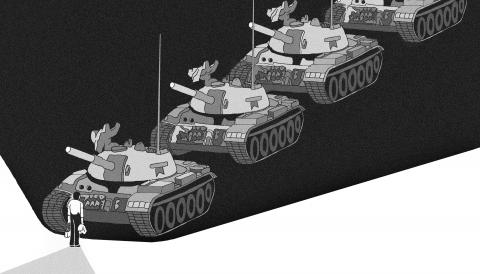

A solitary figure in a white shirt and black trousers clutches a bag and stands in front of a column of halted tanks, a cluster of street lights floating to one side like balloons. The man’s shoulders are rounded, almost passive in front of the four tanks whose gun barrels are raised as if in an ironic salute.

Thirty years on from the violent crushing of pro-democracy protests in Tiananmen Square, the man’s identity remains unknown; it is by no means certain he is still alive.

However, the photograph that captured his solitary moment of dissent in June 1989 remains one of the most memorable images of the past century, known universally as Tank Man.

Illustration: Mountain People

Jeff Widener was not the only photographer to capture the scene, but it is his image — listed as one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential of all time — that has become the most famous.

“Every Tank Man photo has a different flavor. I think I was lucky I was using such a fine-grained film. It allowed it to be blown up larger. I think mine also has a more ‘Gandhi’ feel. He looks more vulnerable: a common man asking a question, like: ‘Why are you doing this?’ My feeling is that this guy had no concern for his safety. He was fed up and just didn’t care. He just wanted answers.”

Speaking to the Observer before the 30th anniversary of the protests, Widener recalled that the picture was almost not taken, as circumstances conspired against him at almost every turn.

UNFORTUNATE EVENTS

On the day Tank Man was taken, June 5, 1989, the then-Associated Press (AP) photographer had flu and was concussed from a blow to the head the night before that had destroyed one of his cameras. He had also run out of film and only managed to secure a roll by asking a US exchange student from whose hotel balcony he was working to scrounge some for him.

Changing lenses in the midst of the encounter, later reimagined in Lucy Kirkwood’s play and television series Chimerica, Widener almost missed the moment, managing to shoot just three pictures before the man with the shopping bags was hustled away.

Of those three photographs, two were not in sharp enough focus. The third, however, made Widener and his unknown subject famous.

“I broke the cardinal rule. I ran out of film. So I asked this kid [the exchange student] to get me more. He’s gone for hours and when he comes back he has one roll of Fuji 100 ISO,” a much slower speed of film than Widener was used to.

Widener decided to take a nap, but was woken by the sound of tanks.

“There’s these four tanks and I think it is a nice composition. Then this guy comes out of nowhere. At first I’m thinking this guy is going to screw up my composition, but the student is shouting: ‘They’re gonna kill him, they’re gonna kill him!’” Widener said.

“He’s just standing there. I’m watching, watching, watching. He’s a long way off,” he said.

Risking missing the photo, Widener, now 62, rushed to grab a teleconverter to double the focal length of his lens, returning to the balcony moments before Tank Man disappeared.

He had just enough time to take one shot in focus, before asking the student to smuggle the film out of the hotel to the US embassy in his underwear from where it could be sent to his office.

It was a tremendous coup for a photographer who was not even based in China, but had been called in to help out the AP’s Beijing office at a time of huge political turmoil.

The unknown Chinese man’s face-off with the tanks came after weeks of demonstrations calling for democratic reforms that had rocked the capital.

Protesters on hunger strike had started to occupy Tiananmen Square on May 13, 1989, and within days they were more than 1 million strong. The army was sent in, and on June 4 soldiers and tanks opened fire on protesters, killing and injuring thousands.

That day, Widener and his colleagues had drawn straws for the night shift. “I remember as I cycled to the square with the correspondent saying I had a bad feeling,” Widener said.

After the carnival-like atmosphere of the preceding days, they could see people putting steel traffic dividers in the middle of the main boulevard.

“I was beginning to feel stressed,” he said.

As AP’s Southeast Asia picture editor born in southern California, he had had little experience of photographing violence. His sense of foreboding was quickly justified.

“I see this guy with a long white beard and he’s laughing. He’s wearing this big heavy coat. And underneath there’s a big bloody hatchet. And that’s a shock,” Widener said.

Continuing toward the Great Hall of the People, Widener could hear screaming and yelling before seeing an armored vehicle moving at speed “with sparks flying off the treads.”

He found himself in the midst of Chinese security forces in their attempts to reoccupy the square and quash the protest movement.

In the chaos that followed he recalls a burning armored vehicle and students with guns taken from soldiers, a dead soldier in the street and another man on fire. As he was getting ready to take a picture a lump of concrete stuck his camera.

‘I WAS TOO SCARED’

“It was like Bugs Bunny. Stars circling. The top of my camera is ripped off and there’s blood coming down,” he said. “I’m totally whacked out, but I’m still trying to get photos when finally I decide to pick up a random bicycle and get back to the office.”

“I could have grabbed another camera and gone out again, but I was too scared. I was shutting down. I had the feeling if I went back I’d die,” he said.

However, the following morning the office received a message from New York. His bosses said they did not want anyone to take unnecessary risks, but asked if it would be possible to photograph the army’s occupation of the square.

“I’m having a nervous breakdown, but, anyway, I’m there to take pictures, so I get on the bicycle,” Widener said.

Getting close to the Beijing Hotel, overlooking the square, he could hear gunfire and see tanks at the intersection, aware of the long lens and camera hidden on him.

“I know there will be secret police at the hotel who’ve been chasing journalists with cattle prods. I get into the lobby and think they’re going to bust me when I see this American exchange student,” he said.

Hailing the young man like a friend, Widener persuaded him to take him to his room, where he took the picture that we all know today.

Widener has since gone on to cover stories all over the world, from Syria to the South Pole.

However, Tank Man stays with him.

“I live with it every day,” he said. “Because no one knows where to find him, they come to me. Don’t get me wrong: I’m not saying I’m Tank Man, but because no one knows who he was, I’m the next best thing, but I can only say what I saw.”

Many foreigners, particularly Germans, are struck by the efficiency of Taiwan’s administration in routine matters. Driver’s licenses, household registrations and similar procedures are handled swiftly, often decided on the spot, and occasionally even accompanied by preferential treatment. However, this efficiency does not extend to all areas of government. Any foreigner with long-term residency in Taiwan — just like any Taiwanese — would have encountered the opposite: agencies, most notably the police, refusing to accept complaints and sending applicants away at the counter without consideration. This kind of behavior, although less common in other agencies, still occurs far too often. Two cases

In a summer of intense political maneuvering, Taiwanese, whose democratic vibrancy is a constant rebuke to Beijing’s authoritarianism, delivered a powerful verdict not on China, but on their own political leaders. Two high-profile recall campaigns, driven by the ruling party against its opposition, collapsed in failure. It was a clear signal that after months of bitter confrontation, the Taiwanese public is demanding a shift from perpetual campaign mode to the hard work of governing. For Washington and other world capitals, this is more than a distant political drama. The stability of Taiwan is vital, as it serves as a key player

Yesterday’s recall and referendum votes garnered mixed results for the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). All seven of the KMT lawmakers up for a recall survived the vote, and by a convincing margin of, on average, 35 percent agreeing versus 65 percent disagreeing. However, the referendum sponsored by the KMT and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on restarting the operation of the Ma-anshan Nuclear Power Plant in Pingtung County failed. Despite three times more “yes” votes than “no,” voter turnout fell short of the threshold. The nation needs energy stability, especially with the complex international security situation and significant challenges regarding

Most countries are commemorating the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II with condemnations of militarism and imperialism, and commemoration of the global catastrophe wrought by the war. On the other hand, China is to hold a military parade. According to China’s state-run Xinhua news agency, Beijing is conducting the military parade in Tiananmen Square on Sept. 3 to “mark the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II and the victory of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression.” However, during World War II, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) had not yet been established. It