Is Mark Zuckerberg too powerful? The Facebook co-founder and chief executive is known to be a fan of the Roman emperor Augustus, although his modern-day empire stretches far further and encompasses many more people: Only China remains unconquered among his 2.2 billion supplicants.

And like an emperor, Zuckerberg can ignore bad news.

There was plenty last week: On Tuesday, Instagram co-founders Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger left Facebook amid suggestions that they were increasingly unhappy with Zuckerberg’s favoring Facebook over Instagram.

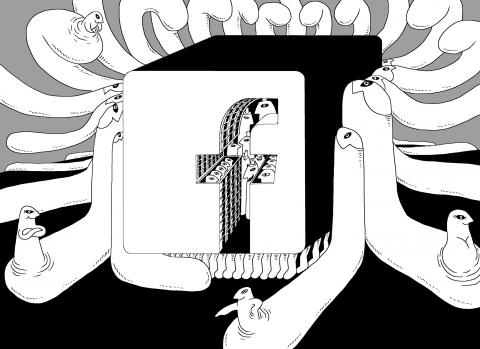

Illustration: Mountain People

Then, on Wednesday, WhatsApp co-founder Brian Acton said in an explosive magazine interview that he regretted having “sold my users’ privacy to a larger benefit.”

A lot of that benefit accrued to him: He — and WhatsApp co-founder Jan Koum — walked away from Facebook in April, forgoing US$850 million in share options, but he was already worth about US$3.6 billion.

That did not stop Acton flagging concerns about Facebook’s interactions with the EU over data privacy, and its promises about what it would and would not do with WhatsApp users’ data.

In many normal companies either of those stories would be enough to start murmurs.

However, with Facebook, the news only strengthened the view that Zuckerberg is in tight control of a giant company within which your ability to navigate internal politics can make you — or frustrate you to breaking point.

For the co-founders of Instagram and WhatsApp, it was the latter.

Why might that make Zuckerberg too powerful? Because Facebook controls the biggest social networks in the world outside China, networks that are becoming less accountable just as it becomes ever harder to escape their grip.

Instagram has 1 billion users, and WhatsApp more than 1.5 billion. The two do overlap, but Facebook benefits from the areas where they do not: US teens who scorn Facebook delight in Instagram; users in developing countries who do not have Instagram dote on WhatsApp.

And although Facebook has not quite figured out how to show adverts to WhatsApp users, it has taken tentative steps toward monetizing them. Its history shows that once it starts, it is unstoppable.

So when Facebook flexes its muscles, rival social networks suffer.

First it strangled Google’s would-be network Google+, launched in 2011. Then, since 2016, Systrom’s task has been to see off fast-rising Snapchat — he succeeded.

Twitter, meanwhile, tried adding a video service — with its more valuable ads — but Facebook and Instagram were there already.

The duopoly that is Facebook and Google together control large sections of the online advertising market — 58 percent this year in the US, according to the digital research firm eMarketer.

However, while Google has come under antitrust examination — and been fined heavily — current law, especially in the US, is silent on the position of social networks.

The standard US antitrust test of “harm to the consumer” fails when a service is free.

Even the EU’s “promoting competition” test stumbles when trying to compare the competitive impact of text-heavy Facebook buying photo-happy Instagram, or messaging-focused WhatsApp.

This shows that antitrust law needs to evolve to encompass the world of social networks. Such takeovers should be blocked if they are on any significant scale, because they work to the detriment of users — who have less choice and are more targeted by advertisers — and suck attention away from rivals who could create fertile competition.

It is instructive to ponder how the world would look if Apple had bought Instagram, as was rumored in 2011, when Instagram was only available on the iPhone, and Google had bought WhatsApp, for which it was bidding.

Instagram would have fewer users and would be like iMessage — only on iPhones. Snapchat and Twitter would surely be bigger. WhatsApp might be only on Android phones. Meanwhile, Facebook would also be smaller.

Would we all have benefited? Probably: The danger of technology is too much concentration of power.

However, those things did not happen and the Internet now has an emperor. It is time for his empire to be broken up.

Back in the 1920s a young Soviet economist called Nikolai Kondratiev came up with a theory that explained the ups and downs of capitalism.

Rather than concentrating on short-term business cycles, he looked at long waves lasting about 50 years that were shaped by advances in technology.

In each cycle there was a pattern. New innovations prompted a surge in investment, which led to higher productivity, higher real incomes and higher consumption.

Eventually, the technology aged and growth slowed until a new cycle of innovation began.

Kondratiev’s theory that capitalism kept reinventing itself was not in line with the Marxist belief of the time and he was shot in 1938 during Joseph Stalin’s purges.

However, it is highly relevant to where the UK and other developed economies stand today.

From one perspective, the slowdown in productivity over the past decade represents a permanent downward shift in growth rates following the financial crisis.

From a Kondratiev perspective, one technological paradigm is exhausted and about to be replaced by the new technologies that will constitute the fourth industrial revolution — including robots, artificial intelligence, biotechnology and quantum computing.

Andy Haldane, chief economist at the Bank of England, last week said that the new wave of innovation would be as transformative as inventions such as the internal combustion engine that emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

However, Haldane made two other points: All periods of technological advance are associated with wrenching social change, and sustained investment in human and physical infrastructure would be needed to disperse the new technologies through the economy.

That requires action by the state. Leaving it to the market will not work.

The hacking scandal will ensure that the history of Rupert Murdoch’s British media empire is tainted, even before weighing the impact of the Wapping dispute and his newspapers’ effect on political discourse.

However, the news last week that the tycoon had agreed to leave Sky — which his 21st Century Fox controls through a 39 percent stake — draws a successful chapter in that history to a close.

The UK’s broadcasting industry, millions of viewers — and a few soccer agents — have benefited from Murdoch’s late-1980s punt that Britain needed a pay-TV broadcaster.

When Sky was launched in 1989, British television was dominated by four channels — there was no local equivalent of CNN and sports broadcasting had none of the pizzazz of the US market.

Sky played a key role in changing that and, nearly 30 years on, the success of Sky News, the global renown of the Premier League and a multimillion-pound investment in original British drama and comedy can all be attributed to Murdoch’s vision.

Soccer has undoubtedly been given a Hollywood makeover under Murdoch’s reign, but big-budget dramas, such as Britannia and Fortitude also reflect the US-level ambition that Sky has brought to British TV.

Sky has helped the UK media industry to think big.

However, that is not to mourn the departure of Murdoch from the scene.

Achievements aside, there is a strong argument that the media industry is stronger for the billionaire’s exit.

Sky’s acquisition by Comcast brings a new, well-funded player to the British broadcasting sector and the media landscape is made more diverse — and plurality strengthened — by limiting one of its most powerful figures to his (still very influential) stable of newspapers.

Cross-media ownership was always one of the concerns about Murdoch’s reach on these shores.

Those worries can now abate, while millions of Sky subscribers continue to reap the benefits.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has long been expansionist and contemptuous of international law. Under Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平), the CCP regime has become more despotic, coercive and punitive. As part of its strategy to annex Taiwan, Beijing has sought to erase the island democracy’s international identity by bribing countries to sever diplomatic ties with Taipei. One by one, China has peeled away Taiwan’s remaining diplomatic partners, leaving just 12 countries (mostly small developing states) and the Vatican recognizing Taiwan as a sovereign nation. Taiwan’s formal international space has shrunk dramatically. Yet even as Beijing has scored diplomatic successes, its overreach

In her article in Foreign Affairs, “A Perfect Storm for Taiwan in 2026?,” Yun Sun (孫韻), director of the China program at the Stimson Center in Washington, said that the US has grown indifferent to Taiwan, contending that, since it has long been the fear of US intervention — and the Chinese People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) inability to prevail against US forces — that has deterred China from using force against Taiwan, this perceived indifference from the US could lead China to conclude that a window of opportunity for a Taiwan invasion has opened this year. Most notably, she observes that

For Taiwan, the ongoing US and Israeli strikes on Iranian targets are a warning signal: When a major power stretches the boundaries of self-defense, smaller states feel the tremors first. Taiwan’s security rests on two pillars: US deterrence and the credibility of international law. The first deters coercion from China. The second legitimizes Taiwan’s place in the international community. One is material. The other is moral. Both are indispensable. Under the UN Charter, force is lawful only in response to an armed attack or with UN Security Council authorization. Even pre-emptive self-defense — long debated — requires a demonstrably imminent

Since being re-elected, US President Donald Trump has consistently taken concrete action to counter China and to safeguard the interests of the US and other democratic nations. The attacks on Iran, the earlier capture of deposed of Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro and efforts to remove Chinese influence from the Panama Canal all demonstrate that, as tensions with Beijing intensify, Washington has adopted a hardline stance aimed at weakening its power. Iran and Venezuela are important allies and major oil suppliers of China, and the US has effectively decapitated both. The US has continuously strengthened its military presence in the Philippines. Japanese Prime