Thao Kae and his friends were foraging for their dinner, collecting the bamboo shoots that grow in the jungle a half-hour’s walk from their remote hamlet along the Mekong River. As they dug and sifted the soil, one of the boys found a small metal sphere and brought it back to a house in the village.

“They thought it was a petanque ball,” said Khamsing Wilaikaew, a 59-year-old farmer, referring to the French bowling game. “They were throwing it against the ground.”

Four decades after it was dropped from a warplane, the metal ball, an American-made cluster bomb, did what it was designed to do. Eight-year-old Thao Kae was killed on the spot. Khamsing’s wife and a nine-year-old boy died of their injuries several days later.

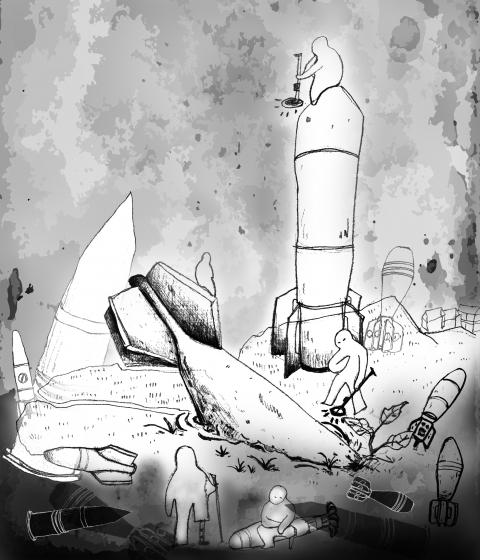

Illustration: Tania Chou

The accident in Houaykhay happened a year and a half ago, but two boys are still limping from untreated and painful injuries to their feet, and the villagers are still traumatized.

They recounted the story on a recent morning to a visitor, Channapha Khamvongsa, an irrepressibly cheery Laotian-American woman. For the past decade she has led a single-minded effort to rid her native land of millions of bombs still buried here, the legacy of a nine-year US air campaign that made Laos one of the most heavily bombed places on earth.

“There are many, many problems in this world that might not be able to be solved in a lifetime,” she said. “But this is one that can be fixed. Given that it was ignored for so long, we need to redouble our efforts and finish the job.”

From 1964 to 1973, US warplanes conducted 580,000 bombing missions over Laos, one of the most intensive air campaigns in the history of warfare. The campaign is often called the Secret War because the US did not publicly acknowledge waging it.

The targets were North Vietnamese troops — especially along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a large part of which passed through Laos — as well as North Vietnam’s Laotian communist allies.

Since the war’s end, more than 8,000 people have been killed and about 12,000 wounded in Laos by cluster bombs and other live, leftover ordnance.

Thanks largely to Channapha’s lobbying, annual US spending on the removal of unexploded bombs in Laos increased to US$12 million this year from US$2.5 million a decade ago.

“The funding increase is almost single-handedly due to the dogged efforts of Channapha,” said Murray Hiebert, an expert on Southeast Asia at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. “She operates from a tiny shoebox operation in Washington with almost no budget. Her only tools are her charm, conviction and persistence.”

US Deputy Assistant Secretary of State Sam Perez called Channapha “a driving force behind the awareness raised and attention gained for unexploded ordnance removal efforts in Laos.”

A vast amount of unexploded ordnance remains in Laos, a mountainous and landlocked former French colony. Clearance teams working across the country pull hundreds of unexploded munitions and bomb fragments from rice paddies and jungle every week. Last year alone, 56,400 munitions were found and destroyed in Laos.

“This country, every time I’ve been here, blows my mind,” said Tim Lardner, a former British army bomb disposal officer who has worked on clearing unexploded ordnance from Laos and other countries for 25 years. “The scale of the contamination is horrendous.”

Having worked in many war-torn countries, including Afghanistan, Cambodia, Angola and Mozambique, he added: “In terms of the amount still in the ground, Laos is worse than any other country I’ve seen.”

Kingphet Phimmavong, the coordinator of the Laotian government’s bomb clearance efforts in Xieng Khouang Province, one of the most heavily bombed areas, said he had found bombs in riverbeds and in termite mounds and tangled in the roots of a tree.

“They are everywhere,” he said.

Tragic stories of bombs unexpectedly detonating are distressingly common. Kingphet’s mother and brother were killed in 1976 when they were tilling a rice paddy and struck a bomb with a hoe.

These days bombs are most often detonated by children who play with them, scavengers seeking scrap metal to sell and villagers who unwittingly build cooking fires near where they are buried.

Three years ago, Nengyong Yang, a farmer in a remote village in Xieng Khouang, was chopping down a tree when a bomblet embedded in the tree trunk exploded and blinded him.

Unable to farm, he later hanged himself, said Maw Khang, 32, his widow, who was left to raise their four children.

“I have to work in the fields, and there is no one to take care of the children,” she said.

Designed to cause maximum casualties to troops, a cluster bomb splits in midair and sprays hundreds of bomblets onto the ground. In Laos, many of these bomblets did not explode for a variety of reasons, including muddy soil that cushioned the impact.

Experts estimate that around 30 percent of the US cluster bombs dropped in Laos remain unexploded.

Despite the scale of the bombing campaign, Channapha, 42, said she became aware of it only as an adult. It was not discussed by her family, who fled Laos in 1979 when she was six, or in the Laotian community where she grew up in Virginia.

“I considered myself somewhat well-read and conscious of right and wrong,” she said. “Yet this major piece of Lao-American history was unknown to me.”

Channapha said she was spurred into action when she came across a collection of drawings of the bombings made by refugees and collected by Fred Branfman, an anti-war activist who helped expose the Secret War.

In 2004, when Channapha founded an organization to raise awareness about unexploded ordnance, Legacies of War, she used the drawings in a traveling exhibition.

Her campaign was initially met with resistance, especially from within the Laotian diaspora in the US.

Laotian-Americans, many of them aristocrats and high-ranking soldiers forced to flee after the US withdrew, were not inclined to help communist-run Laos. Many also wanted to leave the past behind.

“The elders in the community were not supportive,” Channapha said. “They had lost their land, their country, their homes and their status.”

So she rebranded her campaign. Instead of describing it as “a project on the secret US bombing in Laos,” she called its mission “history, healing, hope.”

She brought over a young amputee from Laos who was born after the war and who delivered a message of humanitarian need free from politics.

She targeted members of the US Congress with large Laotian populations in their districts. In 2010, she testified before Congress, urging more funding for bomb clearance and assistance for victims.

And the attitudes of Laotian-Americans have changed in recent years as more have returned to Laos, Channapha said.

“As their own personal relationship with the country was evolving and changing, so did their opinion about what we were doing,” she said. “They were starting to understand that it wasn’t about taking sides.”

Kingphet praises Channapha’s efforts, but he said the US should do more. Many Americans are still unaware of the war in Laos, he said.

“Some Americans come here and they are shocked at how many bombs were dropped,” he said.

The US provided roughly 30 percent of the US$40 million that charities and governments — including those of Australia, Ireland, Japan, Norway and Switzerland — are contributing to clearance efforts this year.

However, even with a surge of money, it will be decades before all the unexploded bombs are removed from the Laotian countryside. In the meantime, officials are traveling to remote corners of the impoverished country and urging caution.

Houmphanh Chanthavong, a government official who was among the group visiting Houaykhay village, told residents of the painstaking process to remove ordnance from the ground, the metal detectors and the clearance experts who delicately dig for them.

“We keep on digging,” he said, “and we keep on finding more.”

There is much evidence that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is sending soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to support Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — and is learning lessons for a future war against Taiwan. Until now, the CCP has claimed that they have not sent PLA personnel to support Russian aggression. On 18 April, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelinskiy announced that the CCP is supplying war supplies such as gunpowder, artillery, and weapons subcomponents to Russia. When Zelinskiy announced on 9 April that the Ukrainian Army had captured two Chinese nationals fighting with Russians on the front line with details

On a quiet lane in Taipei’s central Daan District (大安), an otherwise unremarkable high-rise is marked by a police guard and a tawdry A4 printout from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs indicating an “embassy area.” Keen observers would see the emblem of the Holy See, one of Taiwan’s 12 so-called “diplomatic allies.” Unlike Taipei’s other embassies and quasi-consulates, no national flag flies there, nor is there a plaque indicating what country’s embassy this is. Visitors hoping to sign a condolence book for the late Pope Francis would instead have to visit the Italian Trade Office, adjacent to Taipei 101. The death of

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), joined by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), held a protest on Saturday on Ketagalan Boulevard in Taipei. They were essentially standing for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which is anxious about the mass recall campaign against KMT legislators. President William Lai (賴清德) said that if the opposition parties truly wanted to fight dictatorship, they should do so in Tiananmen Square — and at the very least, refrain from groveling to Chinese officials during their visits to China, alluding to meetings between KMT members and Chinese authorities. Now that China has been defined as a foreign hostile force,

On April 19, former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) gave a public speech, his first in about 17 years. During the address at the Ketagalan Institute in Taipei, Chen’s words were vague and his tone was sour. He said that democracy should not be used as an echo chamber for a single politician, that people must be tolerant of other views, that the president should not act as a dictator and that the judiciary should not get involved in politics. He then went on to say that others with different opinions should not be criticized as “XX fellow travelers,” in reference to