Show me a woman who doesn’t wish her partner did more childcare and I will show you a liar. But how do you get them to do it? I have spent the last five years asking myself this question. Now, finally, an answer has presented itself: Marc and Amy Vachon, advocates of the “50-50 lifestyle” and poster parents for a new American ideal: equally shared parenting.

The Obamas of the parental blogosphere, the Vachons’ profile went global last year when they featured in the New York Times Magazine, complete with pictures of him folding laundry and her practicing piano with the children. I am obsessed with these people and want to be like them.

The Vachons are from Boston, both 46, with two children: Maia, 6, and Theo, 3. Marc works in information-technology; Amy is a pharmacist. They run a Web site, equallysharedparenting.com, and are among a small but committed cohort of evangelists for “post-feminist parenting” where everything is split straight down the middle.

Outside the 32-hour working week they have each negotiated with their employers, the Vachons have a system where everything is shared — from the writing of thank-you letters, to the seasonal rotation of the children’s clothes, cooking, lawn-mowing, recycling, car maintenance, vacuuming and birthday party planning.

“Why is this called anything?” they say modestly of their ultra-democratic home life. “Why isn’t it just called parenting?”

Critics point out that the couple scaled their earning capacity back to work the reduced hours that allow them this lifestyle — and that “the rigid structure they have set up is not practical or desirable for most people.”

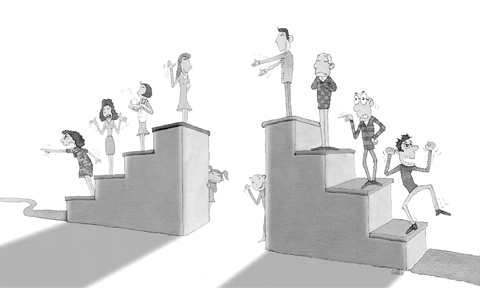

But the Vachons and their fans argue that most mothers are burdened with an unfair “second shift”: working and doing the bulk of childcare. And most fathers are being prevented from having full involvement in their children’s lives.

Their arguments are as valid in Britain as in the US: A 2007 report from the University of Bristol in southwest England shows that women with children put in double the hours at home that men do. Men spend an average of 44 hours a week in paid work and 18 hours in unpaid work. Women spend 26 hours in paid work and 35 hours in unpaid work.

I wonder how a week living by the Vachons’ rules might change us. We both already spend a lot of time with Will, 5, and Vera, 2, and make vague attempts to share. My husband Simon, a radio producer, works a five-day week in central London (we live in Teddington, just outside the capital). He does a school run a couple of times a week and is home by 7pm most nights. I work three days a week from home as a freelance writer.

Overall, it works — although my work can spill unpredictably into the rest of our lives. I am constantly complaining that to achieve “equally shared parenting” my husband would need to work a Vachon-style three or four-day week. After half a decade of nagging, can I finally persuade him? Bring on the Vachon revolution!

DAY 1: SIMON’S LOAD TRIPLES

The experiment starts disastrously when Simon and I cannot agree how many days there are in the week. Do weekends count? We agree on one thing: We will split the nanny’s time. Even Marc and Amy use childminders and nurseries. Our nanny Ola works three days a week between 9am and 5pm. Simon and I are each allocated half of her time in which to work. That leaves two weekdays. One day of childcare each. Simple. We can both work a four-day week. Just like the Vachons. Result.

Or maybe not. Simon has drawn up a spreadsheet. He reckons he can do most of his childcare hours in four-and-a-half workdays; he just needs to put in two hours before school and two hours after work.

He will leave late so he can do the school run and he will come home early at 5:30pm or 6pm. He will take a half-day on Friday and do a day’s childcare at the weekend. And he promises to attend to all nighttime wakings.

It’s double or maybe triple his normal load. It means he will be rushing to and from work and won’t have any free time at home at all. But I am still not happy. I want him to work a three or four-day week. He, however, wants to prove that you can work an almost five-day week and still do equal parenting. We shall see.

I behave pettily on the first day: Simon does the school drop-off and so I ostentatiously do the pickup even though the nanny could easily have done it. I then cook a batch of fiddly pancakes for the children to prove that I also do the larger share of the housework (actually untrue).

Simon quietly gets on with the laundry, tending the fireplace, loading the dishwasher and organizing the recycling bins. Later I fume in my office, surfing Web sites about maternal feminism.

“I hope you will be writing in your article that while you were busy researching the resurgence of the patriarchy, I was cooking your tea,” Simon shouts up the stairs.

DAY 2: VINDICATION, SORT OF

I spend all day looking after the children and feel extremely virtuous. I realize, with a twinge of sadness, that I am being childish. Why am I so angry and competitive? A visit to the dentist reminds me. Simon very rarely has to negotiate everyday life when he looks after the children. He does whatever is easiest — and often they just hang out at home.

Isn’t this what most men do when they look after their children? The fun stuff. Mothers, however, do supermarket shopping, visits to banks and post offices, hairdressing and doctor’s appointments — all with at least one child in tow. It’s exhausting.

In his defense Simon offers to get home in time for the dentist appointment, but it’s at 3.30pm, which would mean him leaving the office at 2.30pm — and taking half a day’s holiday. It makes more sense for me to take them myself and swallow the stress of it.

“Do a lot of mothers bring their children in with them?” I ask the dentist.

“Oh, yes, we get it all the time,” she replies.

“What about fathers?” I ask.

She looks at me blankly. Ha!

DAY 3: SIMON FIGHTS BACK

I work my longest day of the week today and am at the computer at 7am, although I also seem to run up and down stairs for two hours trying to get Vera dressed. (Why isn’t Simon doing this? He is supposed to be “on duty.”)

Simon does the school run with Will. I re-read an e-mail from Marc Vachon. He says one of the biggest problems is when the man’s contribution is seen as “helping” the woman out; that puts her in the position of primary carer. Is this where I’m messing up? Do I think it’s Simon’s duty to “help” me?

Vachon says that men who sign up for equally shared parenting “get guilt-free recreation time for themselves, plus all the benefits of a happy wife who also gets time to pursue her own hobbies and a marriage with true and lasting intimacy (less chance of divorce, a better sex life between two people who appreciate and are attracted to each other).”

I make a note to tell Simon about this.

In the evening we do not experience true and lasting intimacy. Instead we have a row for two hours. I tell Simon that I am livid about his spreadsheet. It should not be about calculating two hours here and two hours there. It should be about him working a three-day week like me. He argues that we cannot be exactly like the Vachons: They both want to work short hours. He doesn’t. I think this is a cop-out. We agree on one thing: We both feel unappreciated by the other.

This is the stuff of marriage guidance counseling. Oh, hell. What have I done?

DAY 4: MY ANTI-VACHON EPIPHANY

I speak to Francine Deutsch, professor of psychology at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts and author of Halving It All: How Equally Shared Parenting Works.

“One of the things that has to happen,” she says, “is for both jobs to be considered equally important.”

Hmm. I often moan that my job takes second place because it’s more flexible. It’s always mothers who scale back, Deutsch adds. She’s right. If a child is sick or there is a calamity, I would expect to drop everything.

But if I’m honest this has got nothing to do with sexism — it’s about practicality. I work from home — in an emergency it would be ridiculous for me to phone Simon and yell: “You have to come home — I’m working.” Common sense trumps fairness. I am beginning to scent bitter defeat. But maybe it’s not such a bad thing.

DAY 5: PATRIARCHY’S REVENGE

A work thing comes up unexpectedly and I have to call my father up to look after Vera. The breadwinner when my sister and I were growing up in the 1970s, he has become our emergency babysitter in recent years.

I am beginning to wish I had never discovered equally shared parenting. It has only served to prove that Simon was right all along: Things are about as equal as they could be.

Simon works a half-day, finishing early to relieve my dad. Meanwhile I have filled out Marc and Amy’s “Toolbox,” which calculates the division of household chores. It turns out I do 21 domestic chores on my own, excelling in the areas of “present-buying” and “organizing childcare” (I employ the nanny). Simon does 19, although his list includes such fripperies as “snow-shoveling” and “assembling toys.” We do 32 things equally, including preparing meals, doing homework and “filing taxes.”

So it turns out we are both right. We are more or less equal. (But I am marginally more put-upon. Hurrah!) I decide not to fill out the section that works out who makes the biggest financial contribution. At the moment it’s me and I have no desire to rub this in Simon’s face. Later, we both agree that there is more to a relationship than childcare or money: There are hundreds of ways in which you support each other that can’t be measured. Or as Simon points out, “I am expecting you to become infirm before I do. So I will probably be looking after you in your later years. That is a priceless contribution.”

Thanks for that.

DAYS 6 AND 7: THE RECKONING

Simon spends all day Saturday looking after the children. I do everything I can to “share” on Sunday. But I still feel guilty. My obsession with doing everything “equally” was stopping me from seeing how much Simon was prepared to do. Before all this started I was on a one-woman mission to get him on the “mommy track” at work.

I still firmly believe that more men should work part-time or flexibly. Then perhaps we will judge people on the quality of their work and their performance rather than on what time they leave the office. But it has taken this experiment to make me realize that this is my bugbear and not Simon’s.

It also occurs to me that we have been more canny than the Vachons. We have split our responsibilities not along gender lines but according to character. It suits me to be a bit of an eccentric workaholic and it suits Simon to have regular hours (and, probably, a place where he can get away from me). And he has realized that by regulating his hours a bit, he can see a lot more of the children.

Marc and Amy are very different. They both work shortish hours in jobs outside the house. It turns out I don’t want their life after all. Instead I am going to embrace the mess.

There is much evidence that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is sending soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to support Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — and is learning lessons for a future war against Taiwan. Until now, the CCP has claimed that they have not sent PLA personnel to support Russian aggression. On 18 April, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelinskiy announced that the CCP is supplying war supplies such as gunpowder, artillery, and weapons subcomponents to Russia. When Zelinskiy announced on 9 April that the Ukrainian Army had captured two Chinese nationals fighting with Russians on the front line with details

On a quiet lane in Taipei’s central Daan District (大安), an otherwise unremarkable high-rise is marked by a police guard and a tawdry A4 printout from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs indicating an “embassy area.” Keen observers would see the emblem of the Holy See, one of Taiwan’s 12 so-called “diplomatic allies.” Unlike Taipei’s other embassies and quasi-consulates, no national flag flies there, nor is there a plaque indicating what country’s embassy this is. Visitors hoping to sign a condolence book for the late Pope Francis would instead have to visit the Italian Trade Office, adjacent to Taipei 101. The death of

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), joined by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), held a protest on Saturday on Ketagalan Boulevard in Taipei. They were essentially standing for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which is anxious about the mass recall campaign against KMT legislators. President William Lai (賴清德) said that if the opposition parties truly wanted to fight dictatorship, they should do so in Tiananmen Square — and at the very least, refrain from groveling to Chinese officials during their visits to China, alluding to meetings between KMT members and Chinese authorities. Now that China has been defined as a foreign hostile force,

On April 19, former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) gave a public speech, his first in about 17 years. During the address at the Ketagalan Institute in Taipei, Chen’s words were vague and his tone was sour. He said that democracy should not be used as an echo chamber for a single politician, that people must be tolerant of other views, that the president should not act as a dictator and that the judiciary should not get involved in politics. He then went on to say that others with different opinions should not be criticized as “XX fellow travelers,” in reference to