Taiwan in Time Jan 28 to Dec. 3

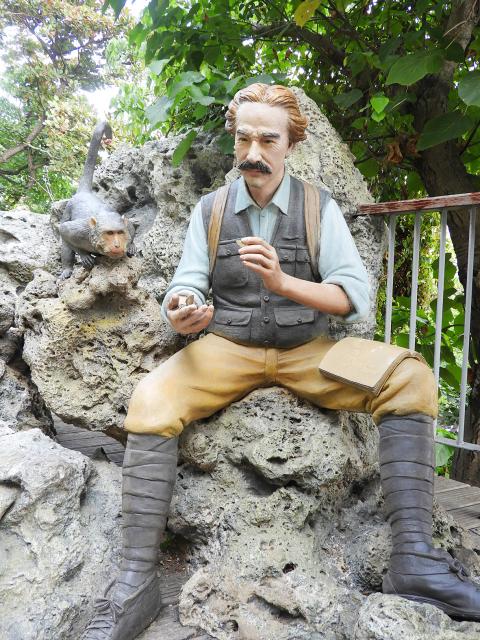

IN just a few years in Taiwan, Robert Swinhoe identified or categorized 227 species of birds, 40 species of mammals, over 200 species of terrestrial snails and over 400 species of insects. The bird count is especially impressive since it amounts to about one-third of the total species in Taiwan. His contributions to the field often dwarf his official role in Taiwan as its first Western consul.

James Davidson wrote in his 1903 book, The Island of Formosa, Past and Present, that no “other foreigner during either the past or present has succeeded in associating his name so firmly with Formosa than the late Robert Swinhoe … Although in Formosa but a few years, so thoroughly possessed was he of that important faculty to the scientist — great powers of observation — that he was enabled to gather much general information about the island, while his contributions on scientific subjects and his discoveries among the birds and beasts of Formosa will carry his name down to posterity.”

Photo: Huang Chih-yuan, Taipei Times

Today, countless species in Taiwan bear Swinhoe’s name, from the Formosan sambar (Rusa unicolor swinhoei) to Taiwan blue pheasant (Lophura swinhoii) to Swinhoe’s Frog (Odorrana swinhoana). In addition, he was the one responsible for certifying that the Formosan macaque was endemic to Taiwan.

In addition to his scientific contributions, Davidson’s book also names Swinhoe as the “first to call to attention of foreigners” to Taiwanese tea, writing a report to the British government and sending samples to several tea inspectors. He also wrote several detailed accounts on Taiwan’s people and customs, including many trips into Aboriginal territory.

ROUND THE ISLAND

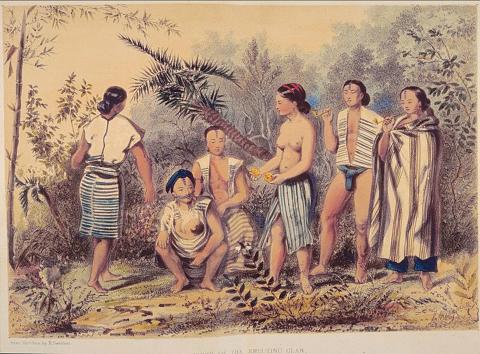

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

While Swinhoe’s name is still known in Taiwan more than a century after his brief stay, his descendants haven’t forgotten about Taiwan either. Last week, Christopher Swinhoe-Standen visited the British Consulate at Takow (打狗英國領事館, in today’s Kaohsiung) to learn more about his ancestor. He also went on a boat tour that briefly followed the route that his ancestor took when he circumnavigated the island in 1857 and 1858 on the British ship Inflexible.

Swinhoe had already visited Taiwan at that point. Born in India, Swinhoe was educated in the UK and joined the China Consular Corps in 1854. His first post was in Xiamen, directly opposite of Taiwan on the Chinese coast. He mastered both Chinese and the local dialect, which is very similar to Hoklo (also known as Taiwanese) and also displayed his scientific talent when he undertook comprehensive research of the birds of eastern China.

There is little information about Swinhoe’s first visit to Taiwan in 1856, but it’s known that the 20-year-old boarded an old Portuguese ship and spent about two weeks in “Hongsan,” documenting four types of bird species. Jackson Tan (陳政三) postulates in the book, Accounts of Robert Swinhoe Hovering over Formosa (翱翔福爾摩沙:英國外交官郇和晚清臺灣紀行), that Hongsan likely refers to Fengshan Village (鳳山) in today’s Hukou Township (湖口) in Hsinchu County.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Tan also argues that the main purpose of the trip was not to collect biological specimens, but to search for European and American castaways from the Kewpie, which was shipwrecked near Taiwan in 1848. Rumors had it that the crew had been enslaved and were toiling in Taiwanese mines.

It was this same missing crew that brought Swinhoe to Taiwan with the Inflexible. Swinhoe published an account of his second voyage in the Journal of the North China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. The account is immensely detailed, including all the flora and fauna that Swinhoe encountered along the way.

He recounts landing “close to some huts,” and some poor but friendly Chinese fisherman came to greet them. The crew offered the fishermen $50 (the currency is not known) for information on each shipwrecked European and $20 for marooned Asians. They later sailed to Tainan, which he called “Taiwan-foo, the capital of Formosa,” noticing that Fort Zeelandia was in ruins with a large tree growing out of the center.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The crew met with the Qing official in charge, who promised to send any castaways he found to Xiamen. He spoke of the “raw savages … who fed on raw flesh and never spared anyone that fell into their hands,” noting that the sailors would definitely be eaten instead of enslaved under them.

“The Chinese had no dealings with the savages, excepting those who were domesticated, and who traded with the settlers,” the official stated.

Other interesting items include stumbling upon two villages that were at war, and visiting the home of outlaw chief Lin Wan-chang (林萬掌), whom the Qing soldiers greatly feared after he drove off an attack on his compound. Lin had an Aboriginal wife, and Swinhoe noted the general mixing of the Han Chinese and Aborigines in these coastal villages. Later, he detailed Han Chinese oppression of the Kavalan people on the Lanyang plains in today’s Yilan County. He also recorded some Aboriginal words.

The mission proved fruitless, and Swinhoe concluded: “From the civilities we received from the Chinese wherever we met them in Formosa, the impression was left on our minds that if any shipwrecked foreigners had fallen into their hands they would have met with every kindness, and been forwarded to some Consular port by the first opportunity; but from what little we saw of the savage Aborigines, the opinion was forced upon us that no unfortunate castaway among them would survive many hours.”

YOUNG DIPLOMAT

In July 1861, Swinhoe arrived in Taiwan again — this time to stay as the island’s first Western consul. Tan writes that the officials in Tainan first looked down on Swinhoe due to his age — he was only 25 — and first had him stay in the Fengshen Temple (風神廟). Chin Mao-hao (金茂號), who Tan calls Taiwan’s richest man, later took him in and helped him find a proper place to lease.

Various diseases still ravaged Taiwan, and three of Swinhoe’s seven servants died of illness. Swinhoe came down with fever himself and headed back to Xiamen to rest for a month. In December 1861, Swinhoe moved the consulate to Tamsui and announced that he would set up a trading port there. Trade had yet to pick up, and being far from Tainan and not in good health, Swinhoe spent much of his idle time exploring the surrounding countryside and villages as well as continuing his documentation of Taiwan’s flora and fauna.

“Swinhoe gave his all to studying birds and beasts, but it seems that he avoided as much responsibility as possible when it came to his ‘real’ job,” Tan writes.

He soon fell ill again and returned to London to recuperate and immediately established his name in British academic circles as an expert on Taiwan. Upon his return to Taiwan in 1864, he moved the consulate to Takao. However, today’s Former British Consulate at Takao wasn’t erected until 1879, long after Swinhoe’s departure.

In April 1866, Swinhoe returned to Xiamen, but he returned several times — first to Penghu to survey coal deposits in 1867, and again in 1868 to deal with the British attack on Anping District (安平) in Tainan.

Swinhoe would write about Taiwan until his death in October 1877. In his last article, On a New Bird from Formosa, he describes the Liocichla steerii and names the bird after Joseph Beal Steere, the naturalist who sent him the specimen. He died just a few weeks later at the age of 41.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

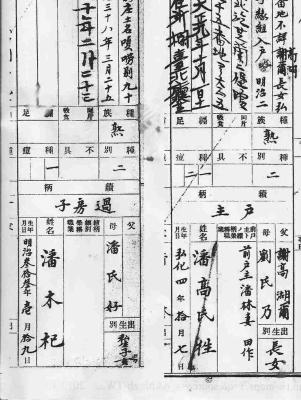

Feb. 9 to Feb.15 Growing up in the 1980s, Pan Wen-li (潘文立) was repeatedly told in elementary school that his family could not have originated in Taipei. At the time, there was a lack of understanding of Pingpu (plains Indigenous) peoples, who had mostly assimilated to Han-Taiwanese society and had no official recognition. Students were required to list their ancestral homes then, and when Pan wrote “Taipei,” his teacher rejected it as impossible. His father, an elder of the Ketagalan-founded Independence Presbyterian Church in Xinbeitou (自立長老會新北投教會), insisted that their family had always lived in the area. But under postwar

On paper, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) enters this year’s nine-in-one elections with almost nowhere to go but up. Yet, there are fears in the pan-green camp that they may not do much better then they did in 2022. Though the DPP did somewhat better at the city and county councillor level in 2022, at the “big six” municipality mayoral and county commissioner level, it was a disaster for the party. Then-president and party chairwoman Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) made a string of serious strategic miscalculations that led to the party’s worst-ever result at the top executive level. That year, the party

In 2012, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) heroically seized residences belonging to the family of former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁), “purchased with the proceeds of alleged bribes,” the DOJ announcement said. “Alleged” was enough. Strangely, the DOJ remains unmoved by the any of the extensive illegality of the two Leninist authoritarian parties that held power in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Taiwan. If only Chen had run a one-party state that imprisoned, tortured and murdered its opponents, his property would have been completely safe from DOJ action. I must also note two things in the interests of completeness.

As much as I’m a mountain person, I have to admit that the ocean has a singular power to clear my head. The rhythmic push and pull of the waves is profoundly restorative. I’ve found that fixing my gaze on the horizon quickly shifts my mental gearbox into neutral. I’m not alone in savoring this kind of natural therapy, of course. Several locations along Taiwan’s coast — Shalun Beach (沙崙海水浴場) near Tamsui and Cisingtan (七星潭) in Hualien are two of the most famous — regularly draw crowds of sightseers. If you want to contemplate the vastness of the ocean in true