Cedric Alviani has returned to journalism after nearly two decades away from the field — but this time, he won’t strive for fair reporting.

“[What I’m doing is] activism,” the director of Reporters Sans Frontieres’ (RSF) new Taipei-based Asia bureau says. “When I’m writing a press release, I won’t be trying to balance between, say, [Hong Kong’s] freedom fighters and the Chinese government. I’m making a choice, because in the matters we are dealing with, not making a choice is already giving in to the strongest.”

Alviani, who has lived in Taiwan for 17 years, says he jumped at the opportunity when he heard that the Paris-based press freedom watchdog was planning to open its first Asia bureau. A graduate of the University of Strasbourg’s School of Journalism, Alviani worked for a regional newspaper for two years before moving to Thailand to work for the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs as part of his military service.

Photo courtesy of Reporters Sans Frontieres

The job later brought him to Taiwan, where he cofounded Infine Communications, which focuses on project management and consulting for various cultural activities. He also started the Taiwan European Film Festival and served as director of the French Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

“I don’t see it as a job,” he says of his new gig. “I had a job. This is a mission.”

A SAFE DISTANCE

Photo courtesy of Reporters Sans Frontieres

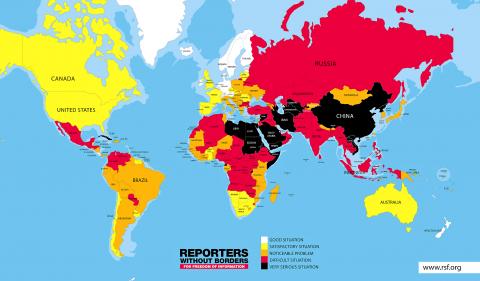

Alviani says he was involved in the decision to set up RSF’s office in Taipei instead of Hong Kong, which has seen its press freedom ranking plummet in the past five years. The culprit is China, he says, which censors anything sensitive to the government and flexes its muscles to influence other governments and private businesses.

“China is stressing the fact that you can have freedom of information with limitations,” he says. “That’s something we don’t agree with. Freedom is something that you either have or you don’t.”

Alviani says since Hong Kong is one of the most crucial areas in his bureau’s battle for press freedom, he didn’t feel safe setting up office there.

“It’s not always a good idea to build your headquarters on the frontlines,” he says. “We would be worried that our team could face intimidation, our communications might be under surveillance, and after a couple of months or years we might be asked to leave.”

Although the office is located in Taipei, Taiwan won’t be a priority for the bureau as it boasts the most liberal press in Asia. While the focus will be on China, Hong Kong and North Korea, Alviani says that they will remain critical of Taiwan’s media environment as well as that of other democracies such as South Korea and Japan.

He adds that Taiwanese authorities shouldn’t be satisfied with being first in Asia.

“I wish Taiwan wasn’t the best in the area (while keeping the same score), because there are still things to improve on here,” he says. “We don’t want to say everything is great — but Taiwan is still moving in a good direction while other Asian countries are not.”

SPREADING THE WORD

Alviani says his first priorities are to develop a network of correspondents in the region who can provide first-hand information as well as translating all information into local languages.

“It’s important that we’re able to communicate in different languages, because the best thing we can do is to bring the problems to the attention of the public and let them decide,” he says, noting the futility of directly asking a government or organization to change their ways.

Another method is to alert international organizations such as the UN on press freedom violations.

“China has entire teams that are trying to lobby in these organizations,” he says. “Of course, we are David and they are Goliath. But we still have to do it.”

RSF might not be welcome in China and North Korea, and Alviani says they might have to get information from Hong Kong and South Korea. However, he will attempt to reach out.

“We’ll go with open hands and friendship and see how the government authorities react,” he says. “We’re not anti-China, as we believe that what we are doing will ultimately be positive for the Chinese people — even though their current government would probably disagree.”

Alviani stresses that media freedom should not be taken for granted, as problems are happening in democracies all around the world, including Taiwan.

“Either political powers or financial powers will always try to [interfere with media freedom] as soon as they feel they are free to do it and as soon as people let them do it,” he says. “It’s extremely important in a democracy … to be able to intimidate [these powers] somehow.”

Taiwan’s problems are similar to that of other democracies — but it also has China trying to interfere with its reporting and editorial content, Alviani says, noting that Chinese propaganda seems to be making its way into Taiwanese media.

“That’s something that Taiwanese probably never would have accepted 10 or 20 years ago,” he says.

Alviani adds that while people should enjoy their freedom, it doesn’t mean that anything goes. For example, publishing photos of naked celebrities or prominent figures.

“Media freedom doesn’t mean you can do whatever,” he says. “Freedom comes with responsibility.”

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,