Inside a shopping mall near Financial Street, past the home decor stores and mannequins dressed in hot-pink lingerie, two friends sipped lattes and debated whether women should shave their armpits.

It was a Thursday afternoon at Lady Book Salon, one of the few bookstores in China geared toward women, and Wang Lu, 32, and Emily Zhou, 29, both investment bankers, were discussing what it meant to be a feminist.

Wang insisted the term was too radical and had become associated with dissidents who wanted sweeping social change in China. Zhou disagreed.

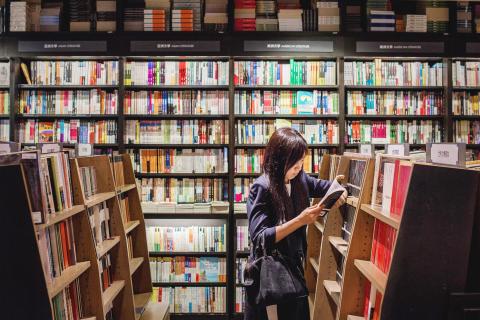

Photo: AFP

“Why should women have to do all these unnatural things, like shaving their armpits, for the sake of men?” she said. “We have to stand up for ourselves.”

REFUGE FOR WOMEN

Since opening two years ago, Lady Book Salon has become a refuge for working women seeking spiritual fulfillment and a place to trade advice on managing families and careers. Bankers, artists, government workers and students come each day in search of books on mindfulness, negotiation, philosophy and women’s rights.

The founder of Lady Book Salon, Xu Chunyu, described herself as a “mild feminist,” saying women should focus on empowering themselves and improving their own lives, rather than striving to change the patriarchy embedded in Chinese culture.

Xu, 41, opened her first female-oriented store in Beijing a decade ago in hopes of giving women a forum for expanding their knowledge of culture, history, feminine identity and relationships. She now operates nine stores in mainland China, each with the slogan, “Be a literary lady!”

Xu said many Chinese women, especially those between the ages of 20 and 45, led a “volatile life,” overwhelmed by the demands of work, family and love.

“I wanted to establish a place for women to express themselves and to show their independence,” Xu said. “Together, they can overcome obstacles and broaden their horizons.”

During a lunch break at Lady Book Salon recently, Philly Ma, 35, sat with a friend at a corner table and cried. Ma said the stress of working at a government financial agency and raising children was overpowering.

“We long for some place to rest the soul,” she said. “This is an oasis in such a chaotic city.”

Su Qing, 33, a manager at a financial services company, started coming to Lady Book Salon last year to read books on business, Chinese history and Buddhism. Su, who struggled with postpartum depression, said that studying Buddhism helped her understand that happiness came not from material wealth but spiritual peace.

“After coming here, I found the direction of my life,” Su said. “Being here has shown I have something beyond my family life, that I have my own interests and activities.”

A LITTLE RESPECT

At another table, Zhang Yuan Yuan, 31, a financial services manager, said she was distraught by the lack of outrage over domestic violence in China. Earlier this month, a video showing a woman being attacked by a stranger in the hallway of a four-star hotel in Beijing went viral. The hotel staff stood idle.

“It’s not an isolated incident,” Zhang said. “There’s not enough respect for women.”

In recent years, the Communist Party has pushed back against some forms of feminist advocacy — last year, it detained five activists who were planning a campaign against sexual harassment — even as the government has portrayed itself as a champion of gender equality.

Vickey Chen, 22, a senior at Beijing Foreign Studies University, said she did not think it helped the cause of feminism to have a bookstore tailored to women.

“You can’t say that we females can only read one kind of book,” said Chen, as she picked up a children’s story and perused a book by Albert Camus. “We should be exposed to all kinds of books.”

Lady Book Salon has tried to please women with both progressive and traditional interests.

Alongside copies of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex and Chinese sociologist Li Yinhe’s Feminism are cake-baking cookbooks and how-to guides on finding husbands. The store hosts talks with female writers and discussions on family and workplace issues, but it also offers classes on making jewelry and applying makeup.

Xu, wearing Buddhist prayer beads on one wrist and a Xiaomi fitness band on the other, said it was important to provide women with both spiritual and practical guidance.

“We have to pay attention to the development of their thoughts and ideas and also help them deal with the realities of their daily lives,” she said.

Customers who visit the store do not have to go far to find reminders of the stereotypes of women that persist in Chinese society.

Lady Book Salon sits directly across from a women’s underwear store. A few feet from its front door is a large advertisement showing a model in black lingerie, surrounded by hearts. Next to the woman are two words: “Perfect Lover.”

Exceptions to the rule are sometimes revealing. For a brief few years, there was an emerging ideological split between the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) that appeared to be pushing the DPP in a direction that would be considered more liberal, and the KMT more conservative. In the previous column, “The KMT-DPP’s bureaucrat-led developmental state” (Dec. 11, page 12), we examined how Taiwan’s democratic system developed, and how both the two main parties largely accepted a similar consensus on how Taiwan should be run domestically and did not split along the left-right lines more familiar in

As I finally slid into the warm embrace of the hot, clifftop pool, it was a serene moment of reflection. The sound of the river reflected off the cave walls, the white of our camping lights reflected off the dark, shimmering surface of the water, and I reflected on how fortunate I was to be here. After all, the beautiful walk through narrow canyons that had brought us here had been inaccessible for five years — and will be again soon. The day had started at the Huisun Forest Area (惠蓀林場), at the end of Nantou County Route 80, north and east

Specialty sandwiches loaded with the contents of an entire charcuterie board, overflowing with sauces, creams and all manner of creative add-ons, is perhaps one of the biggest global food trends of this year. From London to New York, lines form down the block for mortadella, burrata, pistachio and more stuffed between slices of fresh sourdough, rye or focaccia. To try the trend in Taipei, Munchies Mafia is for sure the spot — could this be the best sandwich in town? Carlos from Spain and Sergio from Mexico opened this spot just seven months ago. The two met working in the

This month the government ordered a one-year block of Xiaohongshu (小紅書) or Rednote, a Chinese social media platform with more than 3 million users in Taiwan. The government pointed to widespread fraud activity on the platform, along with cybersecurity failures. Officials said that they had reached out to the company and asked it to change. However, they received no response. The pro-China parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), immediately swung into action, denouncing the ban as an attack on free speech. This “free speech” claim was then echoed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC),