Over the past nine months a number of students at Taiwan Normal University (

Led by Chen Fen-yu (

PHOTO: GAVIN PHIPPS, TAIPEI TIMES

While an agreement regarding the trees, one of which -- the Indian red sandalwood -- is 70 years old, has been reached and permanent homes have been found elsewhere on campus for them, the future of the hall itself remains a hotly debated issue.

PHOTO: GAVIN PHIPPS, TAIPEI TIMES

Although the university doesn't intend to demolish the near 80-year-old, single-story structure, its plans to dismantle it and rebuild it as part of a massive modern building has become the focal point for widespread discussion, especially among the student body.

"Over a three-day period we got over 1,000 students to sign our petition asking the university to reconsider its plans," explained Chen. "We all feel the university considers modernization and prestige more important than [the university's] and Taipei's history."

Part of the university's redevelopment plan, the construction of the Yuezhe Building (

The number of students studying there at present numbers roughly 9,000 and is expected to surpass 10,000 in the coming two to three years. The university also plans to open several new departments in the near future.

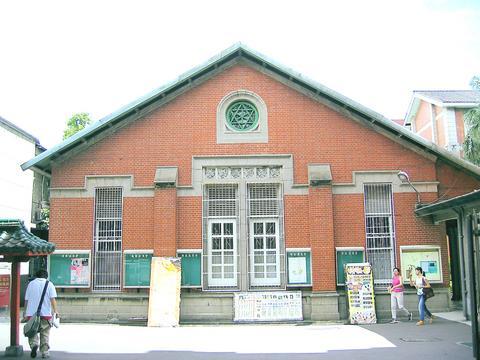

Located on the easterly flank of the university's striking main administration building, the Putong Building (

university's student activity center, the red brick building, which is approximately 30m in length and 12m wide, is now home to the university's oldest on-campus bakery, which has been selling its breads and cakes to students for 70 years.

The Japanese-built structure features elements of colonial architectural style that many feel are important aspects of both the university and the city's cultural heritage.

Features such as the brick pillars, which run along the structure's front porch, as well as the concrete flower-patterned window frames and ornate green lattice widows that adorn the building's northern and southern walls, are seen as irreplaceable.

According to Wang Yi-chun (

It appears that while overseeing the nation's educational policies the MOE does in fact have little say as to what Taiwan Normal University does. A spokesperson for the MOE informed us that contrary to Wang's statement the matter is one for the university itself and does not concern the ministry.

A report issued by the university in March cited the lack of on-campus space as the reason for not being able to relocate the building. A lack of off-campus space and capital to purchase new land were cited as reasons for opting for the on campus site.

All of which is something that Chen and other students find somewhat hard to believe.

"I'm sure if they wanted to move it they could find space somewhere, even somewhere off campus," continued the research student. "Building over and around it might be a simple compromise to leave the building standing. The feel and genuine historical value of it in relation to the surrounding area and its environment will be lost forever, though."

According to a local architect such a move is, while plausible, both a costly and time-consuming process. Each individual piece of the structure has to be tagged and numbered and the slightest damage to one piece could seriously mar the rebuilt structure forever.

When the Taipei Times contacted the university to talk about the plan, we were given access to several reports concerning the new development. Further questions regarding the pros and cons of the matter, however, fell on deaf ears as our messages went

unanswered.

Regardless of the faculty's tight-lipped stance, the great debate moved off campus two weeks ago, when the city government held a public hearing.

Sentiment over the future of the small structure was strong. Over 100 people turned out at City Hall to air their views; a far greater number of people than initially expected.

"There were about 120 people there, which is pretty high, as on average these hearings attract between 20 and 100 people, depending on the issues," Wang said. "It was a very heated debate, with people airing strong opinions about the future of the old building."

According to Wang, both sides of the argument were well represented and it was an evenly balanced debate, leaving him to conclude that the entire affair has put his department is in a catch 22 situation. Whatever the ruling, which is set to take place at the month's end, one side or the other is going to feel that the cultural bureau let them down.

Although feeling somewhat disappointed by such an outcome, as his department doesn't wish to offend anybody, Wang feels the entire affair is sadly indicative of the problems that arise when modernization and development the city clashes with its heritage.

"It is important to keep and maintain our old buildings and the environments in which they stand. They're part of our city's history," he said. "But then, on the other hand, we do need to look to the future. It's a fine line and one that is guaranteed to annoy one side of the argument or the other."

The students opposed to the university's plans are already prepared for the worst; they do have a word or two of warning. Feeling that such plans could spell disaster not only for several other buildings on the campus, but also for other historical buildings throughout Taipei in general.

"If this can happen to one small building, then how many other buildings of historical value will suffer the same fate?" said Chen as she shrugged her shoulders in front of the 80 year-old Wenhui Hall earlier this week.

Last week the story of the giant illegal crater dug in Kaohsiung’s Meinong District (美濃) emerged into the public consciousness. The site was used for sand and gravel extraction, and then filled with construction waste. Locals referred to it sardonically as the “Meinong Grand Canyon,” according to media reports, because it was 2 hectares in length and 10 meters deep. The land involved included both state-owned and local farm land. Local media said that the site had generated NT$300 million in profits, against fines of a few million and the loss of some excavators. OFFICIAL CORRUPTION? The site had been seized

Next week, candidates will officially register to run for chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). By the end of Friday, we will know who has registered for the Oct. 18 election. The number of declared candidates has been fluctuating daily. Some candidates registering may be disqualified, so the final list may be in flux for weeks. The list of likely candidates ranges from deep blue to deeper blue to deepest blue, bordering on red (pro-Chinese Communist Party, CCP). Unless current Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) can be convinced to run for re-election, the party looks likely to shift towards more hardline

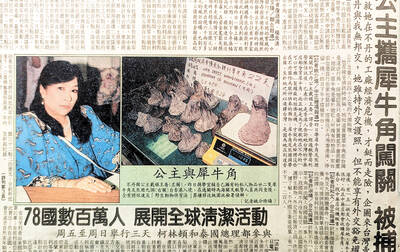

Sept. 15 to Sept. 21 A Bhutanese princess caught at Taoyuan Airport with 22 rhino horns — worth about NT$31 million today — might have been just another curious front-page story. But the Sept. 17, 1993 incident came at a sensitive moment. Taiwan, dubbed “Die-wan” by the British conservationist group Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), was under international fire for being a major hub for rhino horn. Just 10 days earlier, US secretary of the interior Bruce Babbitt had recommended sanctions against Taiwan for its “failure to end its participation in rhinoceros horn trade.” Even though Taiwan had restricted imports since 1985 and enacted

Enter the Dragon 13 will bring Taiwan’s first taste of Dirty Boxing Sunday at Taipei Gymnasium, one highlight of a mixed-rules card blending new formats with traditional MMA. The undercard starts at 10:30am, with the main card beginning at 4pm. Tickets are NT$1,200. Dirty Boxing is a US-born ruleset popularized by fighters Mike Perry and Jon Jones as an alternative to boxing. The format has gained traction overseas, with its inaugural championship streamed free to millions on YouTube, Facebook and Instagram. Taiwan’s version allows punches and elbows with clinch striking, but bans kicks, knees and takedowns. The rules are stricter than the