In 2014, Abdulrahman Saad was taken from his home in Mosul by Islamic State fighters, leaving his family in limbo.

They asked Islamic State security offices and judges: Where is our husband and father?

No answer.

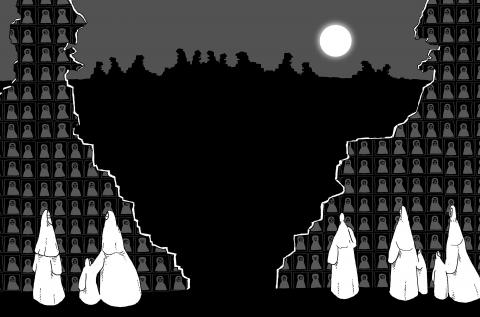

Illustration: Mountain people

When the operation to retake Mosul began, they heard he was being held in the western part of the city, with hundreds of other prisoners, but when the area was liberated, they found no trace of Saad, the 59-year-old owner of a wholesale food store.

“Life without my father is difficult,” son Rami Saad said.

Without him, the Saad family struggle to get by and his wife pines for her spouse.

In their misery, they have company.

Since Mosul was declared liberated in July last year, residents have submitted more than 3,000 missing-persons reports to Nineveh’s provincial council, council member Ali Khoudier said.

Most of them are men or teenage boys. Some were arrested by the Islamic State during the group’s extremist rule; others were detained by Iraqi forces on suspicion of extremist ties.

Regardless, Iraqi government bureaucracy, inefficiency and neglect have left thousands of families across Iraq hanging as the nation’s leadership celebrates the defeat of the militants.

In a small garden outside of a Mosul courthouse, dozens wait to hear if investigators have news of their missing relatives. They cling to thick files of papers — identity documents, official forms, glossy family photographs and “missing person” advertisements from a local paper.

It is unlikely they will hear good news.

“It will be years before these people know what exactly happened to their relatives,” said an investigator, as anxious relatives tapped on the windows behind his desk and hovered at his office door.

The investigator, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said the Iraqi government does not have enough forensic experts to exhume the dozens of mass graves discovered as territory has been retaken from the Islamic State group and the nation’s judicial system is not equipped to efficiently process the thousands of detainees scooped up by security forces.

About 20,000 people are being held at detention centers across Iraq on suspicion of ties to the Islamic State group, according to a report from Human Rights Watch last month.

In Anbar Province, where victory was declared in the cities of Ramadi and Fallujah more than a year ago, more than 2,900 people remain missing, said Mohammed Karbouli, a member of Iraq’s parliamentary committee on defense and security.

He said those missing from Anbar are becoming a symbol of the lack of trust between Anbar’s mostly Sunni residents and the Shiite-dominated central government in Baghdad.

When parents do not know the fate of their children, he said, “tensions emerge.”

Just south of Mosul, an unthinkable number of Iraqis are believed to be buried in a natural sinkhole that became one of the Islamic State group’s most infamous mass graves.

Some Iraqi officials estimate as many as 4,000 people were tossed into the cavernous, natural crevasse in the barren desert on the road linking Mosul to Baghdad — some already dead, others still living and buried alive.

Islamic State fighters “would bring them and make them get out [of the car] and line up at the edge of the hole,” said Mohammed Younis, a resident of the area, recounting the weeks and months leading up to the fight for Mosul. “They would line them up and then they would execute them, and the bodies would all fall into the hole.”

An investigation by The Associated Press has found at least 133 mass graves left behind by the defeated extremists and only a handful have been exhumed. Many of the missing — especially the thousands of Yazidis unaccounted for since Islamic State fighters slaughtered and enslaved the minority — might ultimately be buried there.

Estimates total between 11,000 and 13,000 bodies in the graves, according to the investigation, but not all of the missing were spirited away by the Islamic State group. Some families in and around Mosul say their relatives were taken by unidentified gunmen after the militants were defeated.

“It was the middle of the day, 3:30 in the afternoon. A silver pickup truck drove into the village and took my brother,” Elias Ahmed said as he walked along the dusty main road leading to his home in the sprawling Bijwaniya agricultural village.

Ghazwan Ahmed was taken along with four other young men in August last year. They have not been seen since.

“The men who took him didn’t even identify themselves, they just said they worked in intelligence,” Elias Ahmed said.

Elias Ahmed spent weeks shuttling between the different headquarters of Iraq’s disparate security services in and around Mosul. The federal police, Sunni tribal paramilitary fighters, local police and the Iraqi army all control different sections of Mosul and the surrounding Nineveh countryside.

Each group maintains its own records of detentions and arrests.

Elias Ahmed went looking for answers at a court north of Mosul in the small, historically Christian town of Tel Keif, established especially to process those charged with terrorism.

Each morning, family members gather outside its gates in hope of tracking down missing relatives.

Inside, judges process close to 100 cases a day. Many trials last no longer than 30 minutes.

Yasser Hafahdy, an attorney from Mosul working at the court, defended the practice of arresting people without informing their families where they would be held or the charges against them.

He said the court was overwhelmed by the sheer number of Islamic State suspects arrested and could not spare the time or resources to reach out to families.

Since the court opened its doors in March last year, about a dozen judges have processed more than 15,000 cases. More than 60 percent have been found guilty, Hafahdy estimated.

“What we need is a Judge Dredd, you know, Sylvester Stallone,” Hafahdy said, referring to the 1995 dystopian action film in which a traditional justice system is replaced by armed judges who patrol city streets acting as police, judge, jury and executioner.

At a nearby detention center, hundreds of men sat in cramped rooms, and dozens of women and child detainees shuffled between a windowless room and an open courtyard.

“The Iraqi government was completely unprepared for all the people taken prisoner,” said an Iraqi lieutenant colonel overseeing a different detention center just south of Mosul. “Honestly, we expected more field executions, but human rights organizations were monitoring the operations, so we began taking people prisoner instead.”

The Iraqi officer, who spoke on condition that he was only identified by his rank because he was not authorized to talk to journalists, said that during the Mosul operation hundreds of people passed through his detention center on their way to Baghdad for trials.

During the height of the fighting, the small rooms used as makeshift cells were packed with prisoners.

“We know that this is a violation of human rights,” he said.

The squalid conditions were due to the backlog of cases in Baghdad, he said, and families were unable to track down arrested relatives until the detainees were processed in the capital.

Rami Saad continues to look.

The search has taken him to government detention centers and hospitals in and around Mosul, as well as lawyers’ offices in Baghdad.

Rami Saad traveled to the Iraqi Ministry of Health’s forensic department in Mosul to look over lists of people confirmed killed by the Islamic State group. If Abdulrahman Saad’s death could be established, at least his wife would receive his pension.

“But we didn’t find my father’s name,” Rami Saad said, and so “we have a glimmer of hope. Perhaps he is still alive.”

Additional reporting by Qassim Abdul-Zahra, Salar Salim,

Muhanad al-Saleh and Lori Hinnant

In the first year of his second term, US President Donald Trump continued to shake the foundations of the liberal international order to realize his “America first” policy. However, amid an atmosphere of uncertainty and unpredictability, the Trump administration brought some clarity to its policy toward Taiwan. As expected, bilateral trade emerged as a major priority for the new Trump administration. To secure a favorable trade deal with Taiwan, it adopted a two-pronged strategy: First, Trump accused Taiwan of “stealing” chip business from the US, indicating that if Taipei did not address Washington’s concerns in this strategic sector, it could revisit its Taiwan

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) challenges and ignores the international rules-based order by violating Taiwanese airspace using a high-flying drone: This incident is a multi-layered challenge, including a lawfare challenge against the First Island Chain, the US, and the world. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) defines lawfare as “controlling the enemy through the law or using the law to constrain the enemy.” Chen Yu-cheng (陳育正), an associate professor at the Graduate Institute of China Military Affairs Studies, at Taiwan’s Fu Hsing Kang College (National Defense University), argues the PLA uses lawfare to create a precedent and a new de facto legal

The stocks of rare earth companies soared on Monday following news that the Trump administration had taken a 10 percent stake in Oklahoma mining and magnet company USA Rare Earth Inc. Such is the visible benefit enjoyed by the growing number of firms that count Uncle Sam as a shareholder. Yet recent events surrounding perhaps what is the most well-known state-picked champion, Intel Corp, exposed a major unseen cost of the federal government’s unprecedented intervention in private business: the distortion of capital markets that have underpinned US growth and innovation since its founding. Prior to Intel’s Jan. 22 call with analysts

Chile has elected a new government that has the opportunity to take a fresh look at some key aspects of foreign economic policy, mainly a greater focus on Asia, including Taiwan. Still, in the great scheme of things, Chile is a small nation in Latin America, compared with giants such as Brazil and Mexico, or other major markets such as Colombia and Argentina. So why should Taiwan pay much attention to the new administration? Because the victory of Chilean president-elect Jose Antonio Kast, a right-of-center politician, can be seen as confirming that the continent is undergoing one of its periodic political shifts,