On the day she left for Syria, Sahra strode along the train platform with two bulky schoolbags slung over her shoulder. In a grainy image caught on a security camera, the French teenager tucks her hair into a headscarf.

Just two months earlier and a two-hour drive away, Nora, also a teenage girl, had embarked on a similar journey in similar clothes. Her brother later learned she had been leaving the house every day in jeans and a pullover, then changing into a full-body veil.

Neither had ever set foot on an airplane. Yet both journeys were planned with the precision of a seasoned traveler and expert in deception, from Sahra’s ticket for the March 11 Marseille to Istanbul, Turkey, flight to Nora’s secret Facebook account and overnight crash pad in Paris.

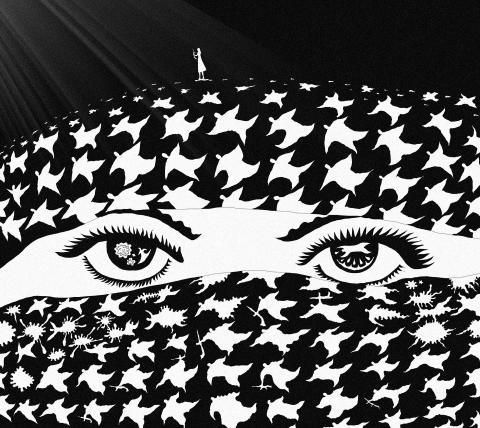

Illustration: Mountain People

Sahra Ali Mehenni and Nora El-Bahty are among about 100 girls and young women from France who have left to join the jihad in Syria, up from just a handful 18 months ago, when the trip was not even on Europe’s security radar, officials say.

They come from all walks of life — first and second generation immigrants from Muslim countries, white French backgrounds, even a Jewish girl, according to a security official who spoke anonymously because rules forbid him to discuss open investigations.

These departures are less the whims of adolescents and more the highly organized conclusions of months of legwork by networks that specifically target young people in search of an identity, according to families, lawyers and security officials.

These mostly online networks recruit girls to serve as wives, babysitters and housekeepers for jihadis, with the aim of planting multi-generational roots for an Islamic caliphate.

Girls are also coming from elsewhere in Europe, including between 20 and 50 from Britain. However, the recruitment networks are particularly developed in France, which has long had a troubled relationship with its Muslim community, the largest in Europe. Distraught families plead that their girls are kidnap victims, but a proposed French law would treat them as terrorists liable to be arrested upon their return.

Sahra’s family has talked to her three times since she left, but her mother, Severine, thinks her communication is scripted by jihadis, possibly from the Islamic State, formerly known as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant.

“They are being held against their will,” said Severine, a French woman of European descent. “They are over there. They’re forced to say things.”

The Ali Mehenni family lives in a red-tiled middle-class home in Lezignan-Corbieres, a small town in the south of France. Sahra, who turns 18 on Saturday, swooned over her baby brother and shared a room with her younger sister. However, family relations turned testy when she demanded to wear the full Islamic veil, dropped out of school for six months and closed herself in her room with a computer.

She was in a new school and she seemed to be maturing — she asked her mother to help her get a passport because she wanted her paperwork as an adult in order.

On the morning of March 11, Sahra casually told her father she was taking extra clothing to school to teach her friends to wear the veil.

Kamel stifled his anxiety and drove her to the train station. He planned to meet her there just before dinner, as he did every night.

At lunchtime, she called her mother.

“I am eating with friends,” she said.

Surveillance video footage showed at that moment, Sahra was at the airport in Marseille, preparing to board an Istanbul-bound flight. She made one more telephone call that day, from the plane, to a Turkish number, her mother said.

By nightfall, she had not returned. Her worried parents went to the police. They noticed the missing passport the next day.

“Everything was calculated. They did everything so that she could plan to the smallest detail,” Severine said. “I never heard her talk about Syria, jihad. It was as though the sky fell on us.”

Sahra told her brother in a brief call from Syria that she had married a 25-year-old Tunisian she had just met, and her Algerian-born father had no say because he was not a real Muslim.

Her family has spoken to her twice since then, always guardedly, and communicated a bit on Facebook. However, her parents no longer know if she is the one posting the messages.

Sahra told her brother she is doing the same things in Syria that she did at home — housework, taking care of children. She says she does not plan to return to France and wants her mother to accept her religion, her choice, her new husband.

Nora’s family knows less about her quiet path out of France, but considerably more about the network that arranged her one-way trip to Syria.

Nora grew up the third of six children in the El-Bahty family, the daughter of Moroccan immigrants in the tourist city of Avignon. Her parents are practicing Muslims, but the family does not consider itself strictly religious.

She was recruited on Facebook. Her family does not know exactly how, but propaganda videos making the rounds play to the ideals and fantasies of teenage girls, showing veiled women firing machine guns and Syrian children killed in warfare. The French-language videos also refer repeatedly to France’s decision to restrict the use of veils and headscarves, a sore point among many Muslims.

Nora was 15 when she departed for school on Jan. 23 and never came back.

The next day, Foad, her older brother, learned that she had been veiling herself on her way to school, that she had a second telephone number and that she had a second Facebook account targeted by recruiters.

“As soon as I saw this second Facebook account I said: ‘She’s gone to Syria,’” Foad said.

The family found out through the judicial investigation about the blur of travel that took her there. First she rode on a high-speed train to Paris. Then she flew to Istanbul and a Turkish border town on a ticket booked by a French travel agency, no questions asked.

A young mother paid for everything, gave her a place to stay overnight in Paris and promised to travel with her the next day, according to police documents. She never did.

Nora’s destination was ultimately a “foreigners’ brigade” for the Nusra Front in Syria, Foad said. The idea apparently was to marry her off. However, she objected and one of the emirs intervened on her behalf. For now at least, she remains single, babysitting children of jihadis. She has said she wants to come home and Foad traveled to Syria, but was not allowed to leave with her.

“As soon as they manage to snare a girl, they do everything they can to keep her,” Foad said. “Girls aren’t there for combat, just for marriage and children. A reproduction machine.”

Two people have been charged in Nora’s case, including the young mother. Other jihadi networks targeting girls have since been broken up, including one where investigators found a 13-year-old girl being prepared to go to Syria, according to a French security official.

“It is not at random that these girls are leaving. They are being guided. She was being commanded by remote control, and now she has made a trip to the pit of hell,” family lawyer Guy Guenoun said.

Additional reporting by Gregory Katz

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has long been expansionist and contemptuous of international law. Under Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平), the CCP regime has become more despotic, coercive and punitive. As part of its strategy to annex Taiwan, Beijing has sought to erase the island democracy’s international identity by bribing countries to sever diplomatic ties with Taipei. One by one, China has peeled away Taiwan’s remaining diplomatic partners, leaving just 12 countries (mostly small developing states) and the Vatican recognizing Taiwan as a sovereign nation. Taiwan’s formal international space has shrunk dramatically. Yet even as Beijing has scored diplomatic successes, its overreach

For Taiwan, the ongoing US and Israeli strikes on Iranian targets are a warning signal: When a major power stretches the boundaries of self-defense, smaller states feel the tremors first. Taiwan’s security rests on two pillars: US deterrence and the credibility of international law. The first deters coercion from China. The second legitimizes Taiwan’s place in the international community. One is material. The other is moral. Both are indispensable. Under the UN Charter, force is lawful only in response to an armed attack or with UN Security Council authorization. Even pre-emptive self-defense — long debated — requires a demonstrably imminent

Since being re-elected, US President Donald Trump has consistently taken concrete action to counter China and to safeguard the interests of the US and other democratic nations. The attacks on Iran, the earlier capture of deposed of Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro and efforts to remove Chinese influence from the Panama Canal all demonstrate that, as tensions with Beijing intensify, Washington has adopted a hardline stance aimed at weakening its power. Iran and Venezuela are important allies and major oil suppliers of China, and the US has effectively decapitated both. The US has continuously strengthened its military presence in the Philippines. Japanese Prime

After “Operation Absolute Resolve” to capture former Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro, the US joined Israel on Saturday last week in launching “Operation Epic Fury” to remove Iranian supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and his theocratic regime leadership team. The two blitzes are widely believed to be a prelude to US President Donald Trump changing the geopolitical landscape in the Indo-Pacific region, targeting China’s rise. In the National Security Strategic report released in December last year, the Trump administration made it clear that the US would focus on “restoring American pre-eminence in the Western hemisphere,” and “competing with China economically and militarily