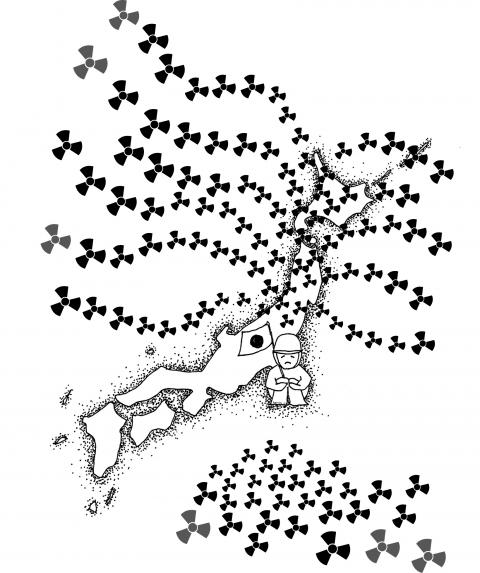

Japan’s nuclear crisis is a nightmare, but it is not an anomaly. In fact, it is only the latest in a long line of nuclear accidents involving meltdowns, explosions, fires and loss of coolant — accidents that have occurred during both normal operation and emergency conditions, such as droughts and earthquakes.

Nuclear safety demands clarity about terms. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission in the US generally separates unplanned nuclear “events” into two classes, “incidents” and “accidents.” Incidents are unforeseen events and technical failures that occur during normal plant operation and result in no off-site releases of radiation or severe damage to equipment. Accidents refer to either off-site releases of radiation or severe damage to plant equipment.

The International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale uses a seven-level ranking scheme to rate the significance of nuclear and radiological events: levels 1 to 3 are “incidents,” and 4 to 7 are “accidents,” with a “level 7 Major Accident” consisting of “a major release of radioactive material with widespread health and environmental effects requiring implementation of planned and extended countermeasures.”

Under these classifications, the number of nuclear accidents, even including the meltdowns at Fukushima Dai-ichi and Fukushima Dai-ni, is low. However, if one redefines an accident to include incidents that either resulted in the loss of human life or more than US$50,000 in property damage, a very different picture emerges.

At least 99 nuclear accidents meeting this definition, totaling more than US$20.5 billion in damages, occurred worldwide from 1952 to 2009 — or more than one incident and US$330 million in damage every year, on average, for the past three decades. And, of course, this average does not include the Fukushima catastrophe.

Indeed, when compared with other energy sources, nuclear power ranks higher than oil, coal and natural gas systems in terms of fatalities, second only to hydroelectric dams. There have been 57 accidents since the Chernobyl disaster in 1986. While only a few involved fatalities, those that did collectively killed more people than have died in commercial US airline accidents since 1982.

Another index of nuclear-power accidents — this one including costs beyond death and property damage, such as injured or irradiated workers and malfunctions that did not result in shutdowns or leaks — documented 956 incidents from 1942 to 2007. And yet another documented more than 30,000 mishaps at US nuclear power plants alone, many with the potential to have caused serious meltdowns, between the 1979 accident at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania and 2009.

Mistakes are not limited to reactor sites. Accidents at the Savannah River reprocessing plant released ten times as much radioiodine as the accident at Three Mile Island, and a fire at the Gulf United facility in New York in 1972 scattered an undisclosed amount of plutonium, forcing the plant to shut down permanently.

At the Mayak Industrial Reprocessing Complex in Russia’s southern Urals, a storage tank holding nitrate acetate salts exploded in 1957, releasing a massive amount of radioactive material over 20,000km2, forcing the evacuation of 272,000 people. In September 1994, an explosion at Indonesia’s Serpong research reactor was triggered by the ignition of methane gas that had seeped from a storage room and exploded when a worker lit a cigarette.

Accidents have also occurred when nuclear reactors are shut down for refueling or to move spent nuclear fuel into storage. In 1999, operators loading spent fuel into dry-storage at the Trojan Reactor in Oregon found that the protective zinc-carbon coating had started to produce hydrogen, which caused a small explosion.

Unfortunately, on-site accidents at nuclear reactors and fuel facilities are not the only cause of concern. The August 2003 blackout in the northeastern US revealed that more than a dozen nuclear reactors in the US and Canada were not properly maintaining backup diesel generators. In Ontario during the blackout, reactors designed to unlink from the grid automatically and remain in standby mode instead went into full shutdown, with only two of twelve reactors behaving as expected.

As environmental lawyers Richard Webster and Julie LeMense argued in 2008, “the nuclear industry … is like the financial industry was prior to the crisis” that erupted that year. “[T]here are many risks that are not being properly managed or regulated.”

This state of affairs is worrying, to say the least, given the severity of harm that a single serious accident can cause. The meltdown of a 500-megawatt reactor located 48km from a city would cause the immediate death of an estimated 45,000 people, injure roughly another 70,000, and cause US$17 billion in property damage.

A successful attack or accident at the Indian Point power plant near New York City, apparently part of al-Qaeda’s original plan for Sept. 11, 2001, would have resulted in 43,700 immediate fatalities and 518,000 cancer deaths, with cleanup costs reaching US$2 trillion.

To put a serious accident in context, if 10 million people were exposed to radiation from a complete nuclear meltdown (the containment structures fail completely, exposing the inner reactor core to air), about 100,000 would die from acute radiation sickness within six weeks. About 50,000 would experience acute breathlessness, and 240,000 would develop acute hypothyroidism. About 350,000 males would be temporarily sterile, 100,000 women would stop menstruating and 100,000 children would be born with cognitive deficiencies. There would be thousands of spontaneous abortions and more than 300,000 later cancers.

Advocates of nuclear energy have made considerable political headway around the world in recent years, touting it as a safe, clean and reliable alternative to fossil fuels, but the historical record clearly shows otherwise. Perhaps the unfolding tragedy in Japan will finally be enough to stop the nuclear renaissance from materializing.

Benjamin K. Sovacool is a professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore.

COPYRIGHT: PROJECT SYNDICATE

In the US’ National Security Strategy (NSS) report released last month, US President Donald Trump offered his interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine. The “Trump Corollary,” presented on page 15, is a distinctly aggressive rebranding of the more than 200-year-old foreign policy position. Beyond reasserting the sovereignty of the western hemisphere against foreign intervention, the document centers on energy and strategic assets, and attempts to redraw the map of the geopolitical landscape more broadly. It is clear that Trump no longer sees the western hemisphere as a peaceful backyard, but rather as the frontier of a new Cold War. In particular,

When it became clear that the world was entering a new era with a radical change in the US’ global stance in US President Donald Trump’s second term, many in Taiwan were concerned about what this meant for the nation’s defense against China. Instability and disruption are dangerous. Chaos introduces unknowns. There was a sense that the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) might have a point with its tendency not to trust the US. The world order is certainly changing, but concerns about the implications for Taiwan of this disruption left many blind to how the same forces might also weaken

As the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) races toward its 2027 modernization goals, most analysts fixate on ship counts, missile ranges and artificial intelligence. Those metrics matter — but they obscure a deeper vulnerability. The true future of the PLA, and by extension Taiwan’s security, might hinge less on hardware than on whether the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) can preserve ideological loyalty inside its own armed forces. Iran’s 1979 revolution demonstrated how even a technologically advanced military can collapse when the social environment surrounding it shifts. That lesson has renewed relevance as fresh unrest shakes Iran today — and it should

On today’s page, Masahiro Matsumura, a professor of international politics and national security at St Andrew’s University in Osaka, questions the viability and advisability of the government’s proposed “T-Dome” missile defense system. Matsumura writes that Taiwan’s military budget would be better allocated elsewhere, and cautions against the temptation to allow politics to trump strategic sense. What he does not do is question whether Taiwan needs to increase its defense capabilities. “Given the accelerating pace of Beijing’s military buildup and political coercion ... [Taiwan] cannot afford inaction,” he writes. A rational, robust debate over the specifics, not the scale or the necessity,