In less than a week, US President Barack Obama will be sitting down with 191 heads of government in New York to review progress on the most ambitious program the UN has ever attempted. In 2000 the world signed up to eight goals, which included halving those living in poverty, establishing universal primary education and reducing by two-thirds the number of children dying before they reach their fifth birthday. The Millennium Development Goals are a fabulous, extraordinary wishlist. Next week all the rhetoric will be about galvanizing commitment, urging one last heave in the final five years to the deadline.

Ahead of next week’s UN summit the aid agencies have produced a blizzard of reports and analyses. Who’s achieved what, which goal is lagging behind and which is completely off track. Most of the headlines that result are about failure: At the current progress more than 1 billion of the world’s population will still be living in extreme poverty in 2015; half of all children in India are malnourished; in sub-Saharan Africa, one child in seven dies before their fifth birthday. For campaigning organizations the goals have been a gift, but associating the development goals with failure is a misreading (and I would argue not a clever move for campaigners on a subject bedeviled by a sense of hopelessness). It’s the proverbial glass half-full, half-empty problem. So here’s the half-full version.

Step back a moment and remember the history. In the 1990s, in the aftermath of the Cold War, aid and development fell off the international agenda. Without an enemy to outmaneuver, the postwar rationale for developed countries to take a close interest in continents such as Africa had vanished. Aid flows fell, many African countries were paying more in interest than they received in aid — yet financial institutions talked of moral hazard in canceling debts (a tune quickly abandoned in the 2008 financial crisis). In the wake of the harsh structural adjustment programs favored by the World Bank and the IMF, a pernicious fatalism had taken hold, characterized as “the poor will always be with us.”

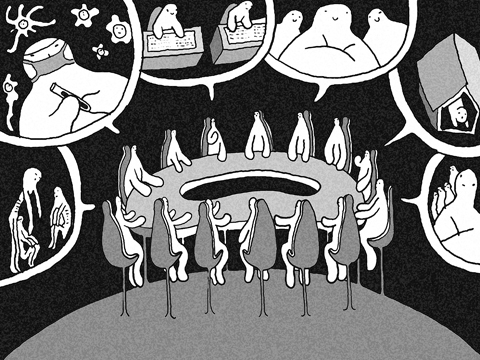

The idea of setting goals was to break this logjam of complacency and apathy. It took several years of pushing and shoving — by, among others, former British secretary of state for international development Clare Short and James Wolfensohn, then president of the World Bank — through international bodies for the eight goals to emerge. Some have been ignored: Goal Eight on global development sketches out such an embarrassingly massive agenda on trade and debt that one expects world peace and universal love to be included.

However, that can’t detract from the bigger picture, which is that the goals galvanized political commitment.

A report from the Overseas Development Institute published this week details some spectacular achievements. Take Ghana, which has been the top global performer on hunger, cutting the rate by 75 percent since 1990: Its rate of child malnutrition has halved. Another success story is Ethiopia, where the hunger rate has fallen from 71 percent to 40 percent. And Vietnam, which has made the most dramatic headway of all: The proportion living on less than US$1 a day has dropped from two-thirds to one-fifth in just 14 years, and it has more than halved the proportion of underweight children. The rate of children dying before their fifth birthday has dropped from 56 to just 15 per 1,000.

There have also been extraordinary achievements in education in sub-Saharan Africa, with startling increases in enrolment rates. Tanzania has jumped from 52 percent to 98 percent since 1991; Benin has gone from 41 percent to 83 percent; Mali from 29 percent to 63 percent and there are plenty of similar statistics. Other goals show great advances: Child mortality has dropped by a third. At the current rate, the goal of halving the number without access to clean water will be met by 2015. These achievements are all the more impressive when you consider the rate of population growth in many countries.

However, there are still plenty to say the glass is half-empty. Economic crisis is plunging millions back below the poverty line, and an issue which barely impinged on the goals in 2000 is now at the forefront of development: climate adaptation. There is a real risk of progress being reversed before 2015. Meanwhile critics argue the goals never recognized the importance of economic growth and were too focused on health and education with no long-term idea of sustainability. However, one issue is emerging to challenge the whole framework of the goals and how they are measured, and that’s how equal they are.

This is the subject many don’t want on the summit agenda. The US does not like the use of the term equity, and the UK’s Department of International Development under its new masters shrinks from the e-word. Aid agencies are nervous of broaching the subject because it irritates developing-country governments. However, there is increasing and embarrassing evidence that the goals are bypassing the poorest in the world. Kevin Watkins of UNESCO points out that in some countries, the most marginalized groups are sometimes even poorer, the expansion of services has failed to reach them and they are falling behind. The figures for development goal indicators are national averages, which conceal the inequality within a country. There was a big row recently at UNESCO when it published analysis of who is falling behind on education and pointed the finger at Turkey, Nigeria, India, Pakistan and Kenya for huge disparities.

So the rosy picture of progress has a shadow side: The improvements of the last 20 years have left significant minorities even further entrenched in poverty and ill health. The one way to tackle this is for the UN summit to put an equity indicator into the goals, so all progress is about narrowing the gap between richest and poorest.

That would mean developing countries making the decision to direct more resources into the slums and remote rural areas where poverty is rife. This has been sensitive territory for the UN, which prefers to talk of global inequality rather than the inequality within developing countries. India, for all its feted economic growth, has barely touched the proportion of those going hungry in the last 20 years. Until now aid agencies have preferred to use failure in the millennium goals as a tool to leverage more aid from the West, but just as crucial is the political will from developing-country governments themselves to reach the poorest and most marginalized.

As Andy Sumner of the Institute of Development Studies points out in a thought-provoking paper, three-quarters of the world’s poorest now live in middle-income countries such as India or Nigeria. This kind of poverty is not about increasing aid, it’s about politics and fair government. There’s a subject they will be avoiding over the canapes next week in New York.

There is much evidence that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is sending soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to support Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — and is learning lessons for a future war against Taiwan. Until now, the CCP has claimed that they have not sent PLA personnel to support Russian aggression. On 18 April, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelinskiy announced that the CCP is supplying war supplies such as gunpowder, artillery, and weapons subcomponents to Russia. When Zelinskiy announced on 9 April that the Ukrainian Army had captured two Chinese nationals fighting with Russians on the front line with details

On a quiet lane in Taipei’s central Daan District (大安), an otherwise unremarkable high-rise is marked by a police guard and a tawdry A4 printout from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs indicating an “embassy area.” Keen observers would see the emblem of the Holy See, one of Taiwan’s 12 so-called “diplomatic allies.” Unlike Taipei’s other embassies and quasi-consulates, no national flag flies there, nor is there a plaque indicating what country’s embassy this is. Visitors hoping to sign a condolence book for the late Pope Francis would instead have to visit the Italian Trade Office, adjacent to Taipei 101. The death of

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), joined by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), held a protest on Saturday on Ketagalan Boulevard in Taipei. They were essentially standing for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which is anxious about the mass recall campaign against KMT legislators. President William Lai (賴清德) said that if the opposition parties truly wanted to fight dictatorship, they should do so in Tiananmen Square — and at the very least, refrain from groveling to Chinese officials during their visits to China, alluding to meetings between KMT members and Chinese authorities. Now that China has been defined as a foreign hostile force,

On April 19, former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) gave a public speech, his first in about 17 years. During the address at the Ketagalan Institute in Taipei, Chen’s words were vague and his tone was sour. He said that democracy should not be used as an echo chamber for a single politician, that people must be tolerant of other views, that the president should not act as a dictator and that the judiciary should not get involved in politics. He then went on to say that others with different opinions should not be criticized as “XX fellow travelers,” in reference to