The fresh-faced 39-year-old man, in a dark T-shirt and jeans, is talking about traveling to Mars. Not now, but when he is older and ready to swap life on Earth for one on the red planet.

“It would be a good place to retire,” he says in all seriousness.

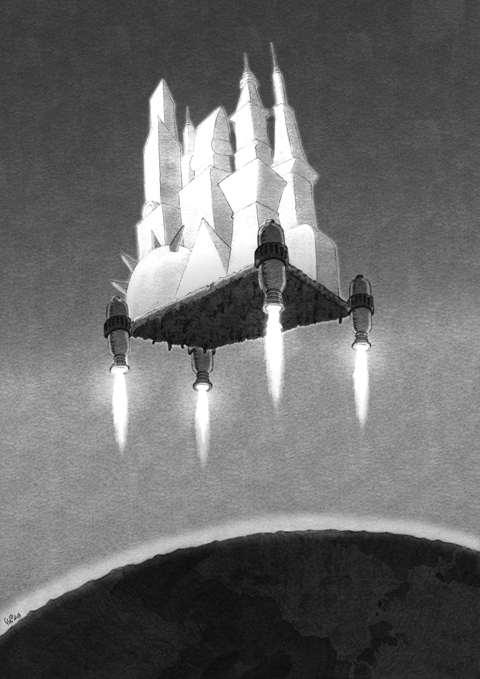

Normally, this would be the time to make one’s excuses and leave the company of a lunatic or to smile politely and humor a space nerd’s unlikely fantasies. However, this man needs to be taken seriously for one compelling reason: He already has his own spaceship.

This is Elon Musk, a brilliant entrepreneur who made a fortune from the Internet and has invested vast amounts of it in building his own private space rocket company, SpaceX. Indeed, far from being crazy, Musk is the real-life inspiration for the movie character Tony Stark, the playboy scientist hero of the Iron Man franchise.

There are some similarities. Outside the SpaceX plant in the baking southern California sun, Musk’s sexy electric sports car sits in a reserved parking space (he cofounded Tesla, the firm which makes the vehicle), resembling the sort of motor Stark would drive. Musk is also engaged to the beautiful British actress Talulah Riley, star of St Trinian’s and St Trinian’s 2, and he used to get thrills from flying his own private military jet fighter.

Moreover, like Stark, Musk is on a mission to save the world. While Stark’s aim was to battle evil-doers and achieve world peace, Musk’s mission is a little grander. He wants to secure humanity’s future by turning the human race into a space-faring people able to colonize other planets. It is the only way, Musk believes, that we can be saved, either from destroying ourselves or from some outside calamity. To put it mildly, Musk thinks big and takes the long view.

“It’s important that we attempt to extend life beyond Earth now,” he says in an accent hinting at his childhood in South Africa. “It is the first time in the 4 billion year history of Earth that it’s been possible and that window could be open for a long time — hopefully it is — or it could be open for a short time. We should err on the side of caution and do something now.”

SpaceX is Musk’s attempt to do that something. Its headquarters are situated within earshot of the busy runways of Los Angeles International Airport. The company’s logo stands proudly on an otherwise nondescript hangar-sized building. Though inside, a revolution in space travel could be taking place.

The factory floor has been roughly organized into an assembly line to make space rockets, part of a process of wresting the future of space travel out of the hands of government bodies, such as NASA and into the hands of private businesses. Using its hyper-efficient Merlin engines, SpaceX has successfully flown its first rocket, Falcon 1, up into space, where it put a satellite into orbit. Then it successfully flew the much bigger Falcon 9 rocket earlier this year. Now the company is working on Dragon, a space capsule that will sit on top of a Falcon 9 and deliver first cargo — and then, hopefully, astronauts — to the International Space Station.

That is stunning stuff. SpaceX, which was only founded in 2002, is not even a decade old. Yet it is doing things in space that some countries with their own national space programs have not yet achieved.

“When we launched the initial rocket actually leaving the launch pad, that was awesome,” Musk says, gazing at the Dragon module being built. “Getting into orbit was when a lot of people thought: OK, it’s real. That’s something that South Korea tried a couple of times and they failed. Brazil tried three times and they failed. This is normally something a country does, and only a few countries have succeeded.”

SpaceX is not alone in aiming for the stars. A raft of private firms have joined in a new space race. Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon, is building a suborbital rocket called the Blue Origin New Shepard. John Carmack, the man behind video games Doom and Quake, has his eyes on a lunar landing. Virgin Atlantic boss Richard Branson is aiming to kickstart space tourism with his Virgin Galactic project. Yet SpaceX is the most advanced and ambitious. Its rockets have already flown into space and it has won hundreds of millions of US dollars worth of business contracts for future voyages.

However, incredibly SpaceX does not feel like a huge operation. It defeats the received wisdom that only major world powers, or gigantic corporations such as Boeing, can truly set their sights on leaving the grip of Earth’s gravity. Instead, SpaceX feels like a dotcom company. Inside the factory are all the accoutrements one expects of a booming Silicon Valley enterprise. All the office space is open-plan and even Musk has an open cubicle like everyone else. Employees — who dub themselves SpaceXers — wear casual T-shirts and are not afraid to sport goatee beards and a smattering of tattoos. They often travel around the assembly floor on tricycles and until recently, before SpaceX’s employee roster topped 1,000 people, Musk was personally involved in every single appointment. He believes the “all in it together” work culture of a start-up is vital to achieve the firm’s staggeringly ambitious agenda.

“People work better when they know what the goal is and why. It is important that people look forward to coming to work in the morning and enjoy working,” Musk says.

In fact, SpaceX’s Silicon Valley-style culture springs from Musk’s own background as one of the most successful — and wealthy — figures to emerge from the Internet.

His interest in technology began early. He bought his first computer at the age of 10 when he was growing up in Pretoria, South Africa, the son of a Canadian model and a South African engineer. Musk taught himself to write computer programs and sold his first commercial software — fittingly, a space game called Blastar — when he was just 12. He left at 17 to work on a relative’s farm in Canada, before going to the University of Pennsylvania.

He graduated with two degrees, one in physics and the other in economics, before winning a place in 1995 at Stanford as a graduate student. He stayed there for two days before fleeing to start his first Internet company, Zip2, which produced publishing software. In 1999, he sold it for more than US$300 million and cofounded X.com, which eventually turned into PayPal. It was sold to eBay in 2002 for US$1.5 billion.

All of which left Musk wealthy beyond belief and could have led to a life of idle bliss. However, besides being a very rich man, Musk is a determined one. Talking to him is a slightly unsettling experience. He is open and friendly, but there is a sense that — on some level — he is operating on a slightly higher plane. Asked why he does what he does, he gives an answer that seems rehearsed, but rings totally sincere.

“When I was in college there were three areas that I thought most would affect the future of humanity. Those were the Internet, the transition to a sustainable energy economy and space exploration and ultimately extending life beyond Earth and making it multi-planetary,” he says.

For Musk, the best way to achieve that third goal was to popularize space travel and make it affordable. Thus, SpaceX and its fleet of rockets were born. He investigated the science behind rocket launching and concluded that there was no real reason why it was so expensive. He believed the space industry was dominated by inefficient government bodies. By starting afresh, and going back to basics, Musk believed getting into space could be done quickly and cheaply.

He was right. SpaceX’s Merlin engines are beautifully engineered and powerful, but simply made. They run on highly refined kerosene that costs less than gasoline. The rockets they power — in the shape of the Falcon 1 and Falcon 9 — are also simple. They have fewer stages (where one bit of the rocket separates from the other) than their rivals and are mostly re-usable. Therefore, they can put cargo into space for a fraction of the cost.

The Dragon module is also a throwback. It looks nothing like the Space Shuttle, which it essentially hopes to replace as the “taxi” service to the International Space Station. Instead, it resembles something from the 1960s, being shaped like a shuttlecock. Not that Musk cares about looks. He just cares about the fact that it is being designed with windows: a sign of his commitment to one day put astronauts, including himself, inside it.

“I would like to go up in a Dragon at some point,” he says. “A few years after its first flying. I think it would be great, huge amounts of fun. A very life-changing experience.”

Of course, Musk’s life has already changed. You cannot be a real-life Tony Stark with plans to retire to Mars and not generate publicity. However, it has not been easy for him. Musk, beneath his shell of otherworldliness, is charming and funny, but he finds being in the public eye difficult. He would prefer to spend his time happily working on his rockets, not giving interviews.

“I had to learn to be a little more extroverted,” he says. “Ordinarily, I would sit in design meetings all day, exchanging ideas with people, but if I don’t tell the story then it doesn’t get out, and I want to try and get public support for extending life beyond Earth.”

Unfortunately, Musk has discovered that celebrity has a dark side. In his case, that was a painful divorce from his ex-wife, Canadian author Justine Musk, with whom he has five children. The split generated its fair share of media attention, not least because Justine has blogged extensively about the epic legal tussles over the terms of their settlement.

As more details emerged, Musk decided to publish his version of events on the Huffington Post. The lengthy piece, in which he wrote about his finances and his relationship with Talulah Riley, began with the words: “Given the choice, I’d rather stick a fork in my hand than write about my personal life.”

Musk’s desire for privacy is perhaps surprising in a man so driven and successful.

“I hate writing about personal stuff,” he says. “I don’t have a Facebook page. I don’t use my Twitter account. I am familiar with both, but I don’t use them.”

Outside work, where he spends up to 100 hours a week, Musk says he devotes nearly all his spare time to being a good dad. His children are the reason he gave up flying his military jet.

“I have five kids and Iron Man does not have any kids,” he says. “After having kids and running companies, I had so many responsibilities I decided it was not wise to take personal risks.”

So are Musk and his entrepreneurial kin the future of space travel? As NASA, the big daddy of the global space business, struggles with reduced budgets and a skeptical public, it seems perfectly possible. SpaceX is getting into orbit for a fraction of the cost of the space shuttle program. It aims to make money as an ongoing business concern, rather than draining an ever-tightening public purse. It wants to drive the costs down and improve reliability and make space travel something that is open to everyone. Only private business, Musk thinks, can do that.

“The fundamental barriers are improving reliability and reducing cost, and the government is not that good at either. Would you prefer to fly Virgin Atlantic or Soviet-era Aeroflot?” he says.

However, Musk remains a dreamer, not just a businessman. He did not create SpaceX to get rich for the second time. Instead, he is risking his fortune to start a company in a field most people said could not support a project like SpaceX. Again and again, he returns to the themes that keep him going. He sees what SpaceX is doing as part of humanity’s destiny.

“I think life on Earth must be about more than just solving problems ... It’s got to be something inspiring even if it is vicarious. When the US landed on the moon it was for all humanity. We count that as a human achievement. Anyone who could get near a TV got near a TV. If there was one TV in an African village and you had to walk [80km] to get there, you’d do it,” he says.

And through it all is the desire to colonize Mars. Musk insists that his most powerful Falcon 9 rockets could already launch missions to Mars if assembled in Earth’s orbit. He wants SpaceX to help humanity spread into space, just like the first European explorers setting out for the New World.

“One of the long-term goals of SpaceX is, ultimately, to get the price of transporting people and product to Mars to be low enough and with a high enough reliability that if somebody wanted to sell all their belongings and move to a new planet and forge a new civilization they could do so,” he says.

Musk’s belief that this can be achieved in two decades is something that most experts would scoff at, but Musk, characteristically, finds it frustratingly slow.

“Twenty years seems like semi-infinity to me. That’s a long time,” he says, as if surprised that anyone could doubt his aims.

It is certainly tempting to dismiss it as a flight of fancy. Except, behind him on SpaceX’s factory floor, Musk’s nascent fleet of working space rockets are already being built.

The US Senate’s passage of the 2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which urges Taiwan’s inclusion in the Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercise and allocates US$1 billion in military aid, marks yet another milestone in Washington’s growing support for Taipei. On paper, it reflects the steadiness of US commitment, but beneath this show of solidarity lies contradiction. While the US Congress builds a stable, bipartisan architecture of deterrence, US President Donald Trump repeatedly undercuts it through erratic decisions and transactional diplomacy. This dissonance not only weakens the US’ credibility abroad — it also fractures public trust within Taiwan. For decades,

In 1976, the Gang of Four was ousted. The Gang of Four was a leftist political group comprising Chinese Communist Party (CCP) members: Jiang Qing (江青), its leading figure and Mao Zedong’s (毛澤東) last wife; Zhang Chunqiao (張春橋); Yao Wenyuan (姚文元); and Wang Hongwen (王洪文). The four wielded supreme power during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), but when Mao died, they were overthrown and charged with crimes against China in what was in essence a political coup of the right against the left. The same type of thing might be happening again as the CCP has expelled nine top generals. Rather than a

Taiwan Retrocession Day is observed on Oct. 25 every year. The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) government removed it from the list of annual holidays immediately following the first successful transition of power in 2000, but the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT)-led opposition reinstated it this year. For ideological reasons, it has been something of a political football in the democratic era. This year, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) designated yesterday as “Commemoration Day of Taiwan’s Restoration,” turning the event into a conceptual staging post for its “restoration” to the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The Mainland Affairs Council on Friday criticized

A Reuters report published this week highlighted the struggles of migrant mothers in Taiwan through the story of Marian Duhapa, a Filipina forced to leave her infant behind to work in Taiwan and support her family. After becoming pregnant in Taiwan last year, Duhapa lost her job and lived in a shelter before giving birth and taking her daughter back to the Philippines. She then returned to Taiwan for a second time on her own to find work. Duhapa’s sacrifice is one of countless examples among the hundreds of thousands of migrant workers who sustain many of Taiwan’s households and factories,