They held elections within days of each other: The Philippines, a lively democracy where politicians get shot dead in the street, and Britain, the rock solid “mother of all parliaments,” but the Asian state’s quick-fire digital vote made the European nation look more like a grandmother as its citizens stuck to the old style of dropping bits of paper in battered old boxes.

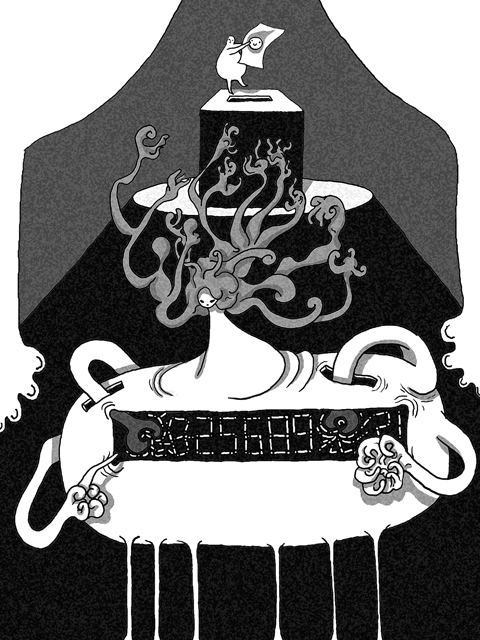

It was hoped electoral automation in the Philippines would cut rampant cheating, where ballot boxes went missing or were stuffed with fake votes and local officials sometimes simply fiddled the results themselves. There was also the logistical nightmare of collecting votes from a country made up of more than 7,000 islands.

The May 10 poll, which was overseen by the government authority Comelec, had some minor glitches, but Comelec Commissioner Gregorio Larrazabal said: “Definitely it was a success.”

“Everybody knows that it worked. There were some kinks that need to be ironed out, but it was generally successful,” he said. “Ask the people on the streets, ask the citizens’ organizations [that] monitored the elections, the teachers who conducted the elections, they say the same thing.”

In Britain, there were angry scenes outside a handful of polling stations that had closed before thousands of people had voted on May 6, leading some commentators to describe it as a “third world” ballot.

“It’s largely a legacy of the Victorian era,” said Jenny Watson, the chairman of the Electoral Commission which sets the standards for running elections for Britain’s 45 million voters.

“It’s not sensible to have a system that was designed when 5 million people were eligible to vote,” she told the BBC.

In the Philippines, Venezuelan company Smartmatic won the contract to run the electronic election. Voters still had to go to a booth and mark a piece of paper, but it was fed into a machine for counting, not a ballot box.

The results were then sent electronically to election headquarters in Manila, with 30 copies printed out and sent to stakeholders as a backup.

“Electronic voting can bring credibility to a country with a bad history of fraud and whose officials are not considered legitimate,” said Cesar Flores, the company’s president for Asia-Pacific. “Electronic voting will be the norm in 20 years from now and only a few countries will remain counting votes manually. It is not a question of if, but when.”

“As long as the system is auditable and recounts are available, the benefits significantly outnumber the possible risks,” he said.

However, it is exactly these risks that make the world’s electoral authorities nervous.

Ingo Boltz, an Austrian electronic election expert, urges caution in adopting automated voting. The human element in traditional elections, he says, can often be its greatest asset.

“With a traditional ballot box, every layperson can, without the use of expert knowledge or tools, follow and verify every step of the election process,” he said. “As long as an observer is physically present, the process is completely transparent to the naked eye. The price of automated voting is the delegation of these tasks to a handful of information technology experts and most IT security experts agree it is basically impossible to guarantee that an e-vote system does exactly what its programmer says it does. We are obliged to trust that programmers are incorruptible.”

As ever more people bank and shop online, will the world soon vote remotely online?

Most election experts think not. The biggest problems of fully remote systems are secrecy and “cyber-terrorism.”

Secret ballots could be compromised, for example, if the patriarch of a large family wanted them all to vote in a particular way — he could be in the room to make sure they did exactly that. Computers could be infected with a virus that would manipulate the vote without the voter ever knowing, or used to launch a denial-of-service attack in which infected computers bombard the system until it overloads and shuts down.

The Open Voting Consortium (OVC), a US advocacy group dedicated to delivering trustworthy elections, was set up after the debacle of the 2000 US presidential elections because, the founders said, “nobody could figure out how Florida’s voters had voted.”

The election was left in disarray partly because of errors in the state’s punchcard system that brought infamy to “chads” — fragments left when holes are made in paper.

The election was so tight and the vote so close in Florida that these voting machine errors became crucial. An OVC electronic voting machine should be available soon.

However, one of OVC’s founders, Alan Dechert, says mass uptake of fully electronic elections is not on the horizon.

“We are a very long way from having a system good enough to be widely trusted for this type of purely electronic voting,” he said. “I don’t see this type of system taking hold in the US over the next 100 years.”

Electronic voting machines are currently used in India and Brazil and have been tested at some level in many other countries, including Britain, but in India there is growing concern after Dutch and US scientists proved that the Indian system can be manipulated and results altered. The Netherlands, Germany and Ireland have all abandoned using electronic voting machines.

Silvana Puizana, an electoral expert who has worked on very different election challenges from Afghanistan and Albania to Suriname and Australia, is also cautious.

“Think of the evils bestowed on so many people by bad governments and governments who will stop at nothing to stay in power,” Puizana said. “The most effective fraud is done by changing results after the count is done — how much easier is that going to be to do undetected when there is no paper trail to trip you up and you, as the corrupt government, control everything anyway. Don’t like the result? Just change it and no one will ever be able to prove you did it.”

“I’ve seen too much fraud and corruption done with impunity to wish to make it even easier for them to do it in the future — with a virtual promise of [it] being undetectable,” she said.

In the first year of his second term, US President Donald Trump continued to shake the foundations of the liberal international order to realize his “America first” policy. However, amid an atmosphere of uncertainty and unpredictability, the Trump administration brought some clarity to its policy toward Taiwan. As expected, bilateral trade emerged as a major priority for the new Trump administration. To secure a favorable trade deal with Taiwan, it adopted a two-pronged strategy: First, Trump accused Taiwan of “stealing” chip business from the US, indicating that if Taipei did not address Washington’s concerns in this strategic sector, it could revisit its Taiwan

The stocks of rare earth companies soared on Monday following news that the Trump administration had taken a 10 percent stake in Oklahoma mining and magnet company USA Rare Earth Inc. Such is the visible benefit enjoyed by the growing number of firms that count Uncle Sam as a shareholder. Yet recent events surrounding perhaps what is the most well-known state-picked champion, Intel Corp, exposed a major unseen cost of the federal government’s unprecedented intervention in private business: the distortion of capital markets that have underpinned US growth and innovation since its founding. Prior to Intel’s Jan. 22 call with analysts

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) challenges and ignores the international rules-based order by violating Taiwanese airspace using a high-flying drone: This incident is a multi-layered challenge, including a lawfare challenge against the First Island Chain, the US, and the world. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) defines lawfare as “controlling the enemy through the law or using the law to constrain the enemy.” Chen Yu-cheng (陳育正), an associate professor at the Graduate Institute of China Military Affairs Studies, at Taiwan’s Fu Hsing Kang College (National Defense University), argues the PLA uses lawfare to create a precedent and a new de facto legal

International debate on Taiwan is obsessed with “invasion countdowns,” framing the cross-strait crisis as a matter of military timetables and political opportunity. However, the seismic political tremors surrounding Central Military Commission (CMC) vice chairman Zhang Youxia (張又俠) suggested that Washington and Taipei are watching the wrong clock. Beijing is constrained not by a lack of capability, but by an acute fear of regime-threatening military failure. The reported sidelining of Zhang — a combat veteran in a largely unbloodied force and long-time loyalist of Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) — followed a year of purges within the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA)