If there is a drier, dustier, more desolate place in the Caribbean I’d be amazed to see it. A few weeks ago, this vast space in Haiti now known as Corail Cesselesse was a vast scraggly grassland about 20km outside the capital, Port-au-Prince.

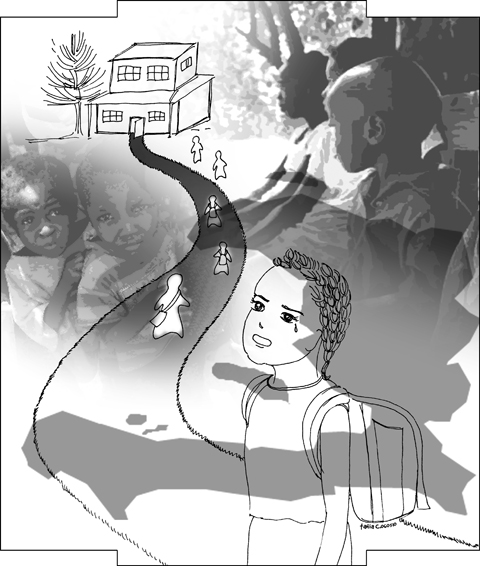

Now, after the magnitude 7.3 earthquake struck Haiti on Jan. 12, it is home to several thousands of the 1.5 million who have been displaced. Many are children — in a country where half the population is under 18 — and for those who have moved to giant camps, they have also been uprooted from their homes, their families and their schools.

Corail is an official camp — the product of interagency cooperation and government consent — and there is plenty of evidence of the foreign money pouring into the country in the aftermath of the earthquake. It is guarded by armed UN guards, and there are well-organized latrines and water tanks.

Plan International, a children’s non-governmental organization (NGO), has provided a school at Corail, while Save the Children is working with the district health office to provide healthcare and treat malnutrition. World Vision is providing food, which is being distributed by the World Food Programme. Like many of Haiti’s large camps, education at Corail is a work in progress. A large empty tent at the back of the camp has just started receiving three to five-year-old children for kindergarten classes and is expecting more than 200 in separate morning and evening shifts.

Access to kindergarten is limited in Haiti and for many children in the camp, this is their first experience of learning.

“Some of them cried a little bit today, as it was the first day,” said Jeanette, who is in charge of early learning at Corail. “We rocked them, played with them, had some balloons. After that they were comfortable — they stayed until the end. Some didn’t want to leave.”

It’s hard to imagine a more enthusiastic kindergarten teacher than Jeanette, who bounces around, despite the oppressive dust and heat, showing off the finger puppets and toys she uses to entertain the children.

However, there are still no tables or chairs for the classroom, and furniture ordered by Plan to equip the school has yet to arrive. The difficulty in getting urgently needed materials into the country is one of the greatest post-disaster challenges in Haiti and has had a massive impact on schools.

“Getting materials to equip the schools has been one of the biggest logistical issues,” said Damien Queally, emergency manager at Plan Haiti. “At the moment, we have only been able to meet 10 percent of the overall need at the schools we are supporting.”

Part of the problem is clearing imported goods through customs, which takes weeks, and the massive logistical challenges of transporting heavy goods through Haiti’s already limited and now damaged infrastructure, with little capacity to unload trucks and containers.

At the Fleur de Chou primary school in the Croix-des-Bouquets area just outside Port-au-Prince, classes are taking place in a tight space around the collapsed school buildings.

Unlike some schools which lost everything, here some furniture was salvaged from the old school, but the tents being used to house temporary classrooms have plastic roofs, which allow in direct sunlight that is affecting children’s eyes. No one is sure what will happen when the rains begin — as the rainy season starts any day now.

“Our main priority is a new school. We desperately need a new school,” says Marie Florvie Dorestan, head teacher at Fleur de Chou.

Fleur de Chou, like 83 percent of Haitian schools, is private. The fees are 600 gourdes a month — about US$15 — and many of the students are from relatively poor backgrounds, with parents who make a living by selling food and cooking oil. However, the earthquake left many families without livelihoods, and almost all of Haiti’s schools have no income from fees to pay their staff.

The Ministry of Education, World Bank and other donors have been negotiating a US$500 million fund that would pay private schoolteachers from January to the end of a specially extended school year in August, but the lack of unified salaries or fees across the thousands of different private schools has made this difficult to organize.

The prospect of schools closing down due to a lack of funding is of particular concern in post-earthquake Haiti, as schools fulfill an increasingly social function for traumatised children.

In Nwayo, a camp of 3,000 people outside Croix-des-Bouquets, children who do have access to school have begun attending a “child-friendly space,” where they can play safely, away from the troubles of the camp.

“The majority of kids did not go to school before the earthquake,” said Reuben Emmanuel, principal of the child-friendly space at Nwayo. “Now they are in the child-friendly space taking the opportunity to have some education.”

However, there are serious questions about malnutrition at Nwayo. An informal camp, it lacks the interagency support of the formal camps such as Corail Cesselesse. Plan had a pre-existing relationship with the local community and has established the child-friendly space, but there are no latrines, sanitation facilities or food programs.

As with most land in Haiti, the site at Nwayo is privately owned, and the residents have to obtain the proprietor’s consent for permission to use it. Many of the children have ginger hair and swollen bellies — symptoms of serious malnutrition — and there is evidence of parasites and illness, too.

Jean Pierre, 13, goes to the child-friendly space at Nwayo, but says it is difficult to concentrate because he is hungry.

“We don’t have enough to eat. Sometimes when we find money, we buy food. Sometimes we don’t find money and we don’t have enough. I feel hungry when I come here,” he said.

“I hope it’s temporary,” Jean Pierre said. “Everything has a start and an end.”

“I don’t like it here,” said Richmid, age 12. “I can’t find water to drink. I don’t have enough to eat. My mother used to sell things for a living, but now she doesn’t work. All we saved from our house was one cup, plate and spoon — all the rest of our things are under the rubble.”

“This center is the best thing in my life right now,” Richmid said.

The role NGOs are playing in education in Haiti is vital, but raises serious questions about the future of education and all public services in the country. All have been badly affected by the earthquake and are struggling to fill emergency posts in key positions like child protection and relief work.

Many professionals in the sector are concerned about the lack of governance from Haiti’s government, which has suffered from long-term dependence on aid, as well as endemic problems of corruption and incompetence.

“The Ministry of Education is trying to get children back to school, but their president is working out of a police station,” Queally said. “Before the earthquake only half of children went to school. The ministry now wants all private schools to be free and agency-subsidized, but there is no clear strategy emerging for longer-term emergency plans.”

When I asked the deputy minister for education about the government’s strategy for education in the camps, his response was that this was the responsibility of the regional director of education. When I asked the regional director of education, he directed me back to the minister.

The lack of governance is likely to prove a major obstacle to the meaningful reconstruction and improvement of education in Haiti once disaster relief efforts are over. NGOs are hoping to use education as a way of reaching out to traumatized children and investing in the future of Haiti’s next generation, but, like Plan, only tend to operate in formal camps or areas where they have a pre-existing history.

The complexities of the redevelopment program and UN-based “cluster system” for coordinating relief work are over the heads of many children, though, whose priority is going to school and who are often bemused by the influx of foreign workers.

“A lot of strangers come here,” one eight-year-old boy told me, as he ate sweet plantains from a little Tupperware box during his morning break at Fleur de Chou.

“I like them. I don’t know if they have helped us, but they wear nice clothes and have long hair,” he said.

There is much evidence that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is sending soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to support Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — and is learning lessons for a future war against Taiwan. Until now, the CCP has claimed that they have not sent PLA personnel to support Russian aggression. On 18 April, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelinskiy announced that the CCP is supplying war supplies such as gunpowder, artillery, and weapons subcomponents to Russia. When Zelinskiy announced on 9 April that the Ukrainian Army had captured two Chinese nationals fighting with Russians on the front line with details

On a quiet lane in Taipei’s central Daan District (大安), an otherwise unremarkable high-rise is marked by a police guard and a tawdry A4 printout from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs indicating an “embassy area.” Keen observers would see the emblem of the Holy See, one of Taiwan’s 12 so-called “diplomatic allies.” Unlike Taipei’s other embassies and quasi-consulates, no national flag flies there, nor is there a plaque indicating what country’s embassy this is. Visitors hoping to sign a condolence book for the late Pope Francis would instead have to visit the Italian Trade Office, adjacent to Taipei 101. The death of

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), joined by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), held a protest on Saturday on Ketagalan Boulevard in Taipei. They were essentially standing for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which is anxious about the mass recall campaign against KMT legislators. President William Lai (賴清德) said that if the opposition parties truly wanted to fight dictatorship, they should do so in Tiananmen Square — and at the very least, refrain from groveling to Chinese officials during their visits to China, alluding to meetings between KMT members and Chinese authorities. Now that China has been defined as a foreign hostile force,

On April 19, former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) gave a public speech, his first in about 17 years. During the address at the Ketagalan Institute in Taipei, Chen’s words were vague and his tone was sour. He said that democracy should not be used as an echo chamber for a single politician, that people must be tolerant of other views, that the president should not act as a dictator and that the judiciary should not get involved in politics. He then went on to say that others with different opinions should not be criticized as “XX fellow travelers,” in reference to