“Literature describes a descent,” writes Martin Amis in his novel The Information. “First Gods, then demi-Gods. Then epic became tragedy, failed kings, failed heroes, then the gentry, then the middle class and its mercantile dreams. Then it was about you — social realism. Then it was about them — low life, villains, the ironic age,” he wrote.

Yet in this cavalcade of whiskery generals and noble proles one group has gone almost ignored: the bankers. Victorian readers could at least turn to Antony Trollope’s Melmotte and Charles Dickens’ Merdle; their descendants have had almost nothing. One can imagine the financiers’ response as they waited for those writers to call them back: the initial hurt, hardening into a resolve to be more alluring — to work out more, perhaps, or wear racier ties. Or, best of all, to trigger an almighty economic meltdown.

Only when the money class is having a near-death experience do members of the leisure class — writers and filmmakers — reach for their Apple Macs. The insider trading scandals and stock market collapse of the 1980s prompted Oliver Stone to make Wall Street, Michael Lewis to write Liar’s Poker and Tom Wolfe to bring out Bonfire of the Vanities. This time, amid the biggest slump since 1921, there’s been a TV drama about Lehmans, plays including Lucy Prebble’s Enron and a clutch of books.

“A dramatist seeks to understand the financial crisis” is David Hare’s subtitle to The Power of Yes, and it could serve as a group objective. This is art as public service: a primer on the credit crunch. It’s also literature as the case for the prosecution: Hare even puts himself on stage, grilling his cast of regulators and bankers about the finer details of options pricing like a corduroy-clad Columbo.

Lieutenant Hare makes the case that the crisis was caused by ministers, economists and financiers acting as if they had come to the end of economic history. But what is most striking about The Power of Yes is how remote it renders a still-unfolding event. Hare offers a “story,” eyewitness accounts from George Soros and private equity baron Ronnie Cohen; the burning wreck as viewed from up high by the Davos set.

Faced with a catastrophe that has ruined everyone from subprime homeowners in San Diego to venerable Swiss bankers, nearly all the crisis literature falls back on portraits of cosy elites.

Marking the first anniversary of the banking crisis in September, the BBC drama The Last Days of Lehman Brothers should have been titled “Men on the Verge of a Systemic Breakdown.” It can be summarized thus: Alpha males squabble around a table; alpha males fail to strike a deal; Christendom goes bust. Meanwhile Dick Fuld, boss of the soon to be ex-bank, broods in his office, less King Lear than Blofeld in a business suit.

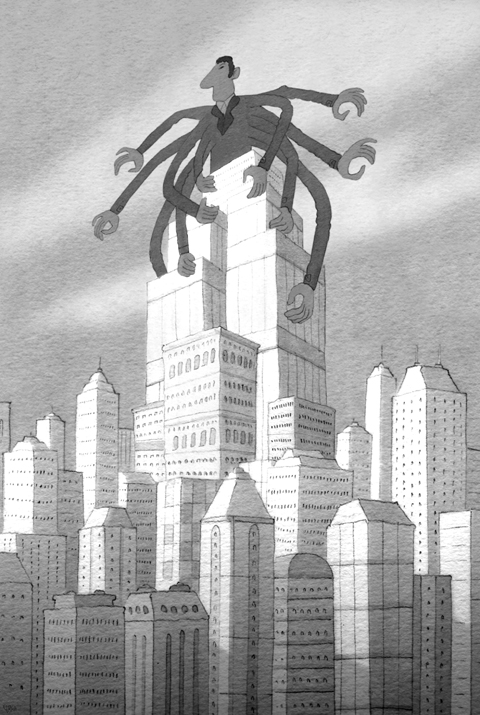

This is banking as a boys’ club: Decisions made in boardrooms that somehow affect the rest of the world. It takes no account of the expansion of wholesale finance since the late 1980s, nor of the fact that Fuld and other executives had little idea of the balance sheet explosives traded by their underlings. Yet this is the story that publishers also want to tell us. Take, for instance, the fast-growing sub-genre of books that we might call the Credit Crunch Confessional.

Bearing titles such as How I Caused the Credit Crunch, the confessional purports to give the insider’s perspective. To fit the genre a book must: a) be written by someone who once worked at a bank and b) mix one part explanation with nine parts City sleaziness. The subtitle to Seth Freedman’s book, “The real inside story of cash, cocaine and corruption in the City,” sets the tone.

Hack your way through the dead sentences, and the same story is repeated over and over: Finance is about barrow boys and Oxford blues indulging in cartoonish excess on trading floors or in fancy restaurants with Cristal and “palette-cleansing” cocaine. Sex and drugs and lap-dancing clubs: these are not so much exposes of banking as insights into what happens when you pay 20-something dullards too much money.

High finance today comprises thousands of people doing lots of little things that together produce huge consequences. It’s a business built not on long-term relationships but transactions. A few years ago, the London Review of Books published the diary of a trader who had jacked in his theology doctorate to spend every waking hour watching Polish interest rates.

“Dozens of bright minds are bent exclusively towards [one] number, working lives spent gauging moment by moment whether it’s too high or too low,” he wrote. “If there’s something absurd about this expense of energy, the sums of money that can be lost or made provide an offsetting seriousness.”

The challenge for writers, then, is to show markets as things of monstrous scale and volatility, with workers bombarded by information and demands from the boss, clients and colleagues; more The Wire with its minor characters trapped in failing systems than the charismatic evil of Gordon Gekko.

Of all this year’s crisis literature, Enron gets closest, with its whirling traders and stock prices burnt on human faces. Prebble thinks film may be the only medium with the scope to do banking justice.

“But the producers would ask, ‘Who’s going to be the hero — and which actress will he save from financial ruin?’” she said.

Perhaps audiences are ahead on this one. They may not follow the technicalities or like the bonuses, but the growing influence of markets over the last couple of decades means many have still been sucked into the culture of finance. Pop into those new city center offices, and chances are they’ll be as open-plan and anonymous as any trading floor.

Think of the way private-sector firms are run now: outsourced, offshored, just in time. Modern public sector managers use the terminology of shareholder value — best performance value indicators and all that.

Writers and filmmakers have failed so far to give bankers their due representation; but the financiers are making their mark on the culture all right.

There is much evidence that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is sending soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to support Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — and is learning lessons for a future war against Taiwan. Until now, the CCP has claimed that they have not sent PLA personnel to support Russian aggression. On 18 April, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelinskiy announced that the CCP is supplying war supplies such as gunpowder, artillery, and weapons subcomponents to Russia. When Zelinskiy announced on 9 April that the Ukrainian Army had captured two Chinese nationals fighting with Russians on the front line with details

On a quiet lane in Taipei’s central Daan District (大安), an otherwise unremarkable high-rise is marked by a police guard and a tawdry A4 printout from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs indicating an “embassy area.” Keen observers would see the emblem of the Holy See, one of Taiwan’s 12 so-called “diplomatic allies.” Unlike Taipei’s other embassies and quasi-consulates, no national flag flies there, nor is there a plaque indicating what country’s embassy this is. Visitors hoping to sign a condolence book for the late Pope Francis would instead have to visit the Italian Trade Office, adjacent to Taipei 101. The death of

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), joined by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), held a protest on Saturday on Ketagalan Boulevard in Taipei. They were essentially standing for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which is anxious about the mass recall campaign against KMT legislators. President William Lai (賴清德) said that if the opposition parties truly wanted to fight dictatorship, they should do so in Tiananmen Square — and at the very least, refrain from groveling to Chinese officials during their visits to China, alluding to meetings between KMT members and Chinese authorities. Now that China has been defined as a foreign hostile force,

On April 19, former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) gave a public speech, his first in about 17 years. During the address at the Ketagalan Institute in Taipei, Chen’s words were vague and his tone was sour. He said that democracy should not be used as an echo chamber for a single politician, that people must be tolerant of other views, that the president should not act as a dictator and that the judiciary should not get involved in politics. He then went on to say that others with different opinions should not be criticized as “XX fellow travelers,” in reference to