Idon’t know when global oil supplies will start to decline. I do know that another resource has already peaked and gone into free fall — the credibility of the body that’s meant to assess them.

Last week two whistle-blowers from the International Energy Agency (IEA) alleged that it has deliberately upgraded its estimate of the world’s oil supplies in order not to frighten the markets. Three days later, a paper published by researchers at Uppsala University in Sweden showed that the IEA’s forecasts must be wrong, because it assumes a rate of extraction that appears to be impossible. The agency’s assessment of the state of global oil supplies is beginning to look as reliable as former Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan’s blandishments about the health of the financial markets.

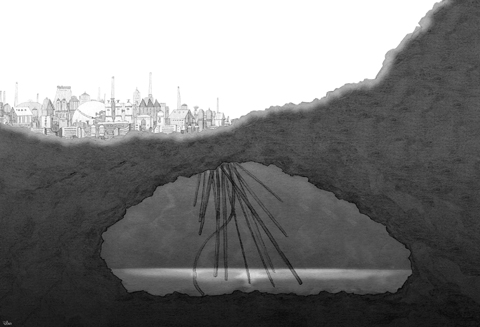

If the whistle-blowers are right, we should be stockpiling ammunition. If we are taken by surprise, if we have failed to replace oil before the supply peaks then crashes, the global economy is stuffed, but nothing the whistle-blowers said has scared me as much as the conversation I had last week with a farmer in Pembrokeshire, southwest Wales.

Wyn Evans, who runs a mixed farm of 69 hectares, has been trying to reduce his dependency on fossil fuels since 1977. He has installed an anaerobic digester, a wind turbine, solar panels and a ground-sourced heat pump. He has sought wherever possible to replace diesel with his own electricity. Instead of using his tractor to spread slurry, he pumps it from the digester on to nearby fields. He’s replaced his tractor-driven irrigation system with an electric one and set up a new system for drying hay indoors, which means he has to turn it in the field only once. Whatever else he does is likely to produce much smaller savings, but these innovations have reduced his use of diesel by only around 25 percent.

Farm scientists at Cornell University say cultivating one hectare of maize in the US requires 40 liters of gasoline and 75 liters of diesel. The amazing productivity of modern farm labor has been purchased at the cost of a dependency on oil. Unless farmers can change the way it’s grown, a permanent oil shock would price food out of the mouths of many of the world’s people. Any responsible government would be asking urgent questions about how long we have got.

Instead, most of them delegate this job to the IEA. I’ve been bellyaching about the British government’s refusal to make contingency plans for the possibility that oil might peak by 2020 for the past two years and I’m beginning to feel like a madman with a sandwich board.

Perhaps I am, but how lucky do you feel?

The new World Energy Outlook published by the IEA last week expects the global demand for oil to rise from 85 million barrels a day last year to 105 million in 2030. Oil production will rise to 103 million barrels, it says, and biofuels will make up the shortfall. If we want the oil, it will materialize.

The agency does caution that conventional oil is likely to “approach a plateau” toward the end of this period, but there’s no hint of the graver warning that the IEA’s chief economist issued when I interviewed him last year: “We still expect that it will come around 2020 to a plateau ... I think time is not on our side here.”

Almost every year the agency has been forced to downgrade its forecast for the daily supply of oil in 2030 — from 123 million barrels in 2004, to 120 million in 2005, 116 million in 2007, 106 million last year and 103 million this year. According to one of the whistle-blowers, however,”even today’s number is much higher than can be justified and the International Energy Agency knows this.”

The Uppsala report, published in the journal Energy Policy, anticipates that maximum global production of all kinds of oil in 2030 will be 76 million barrels per day. Analyzing the IEA’s figures, it finds that to meet its forecasts for supply, the world’s new and undiscovered oil fields would have to be developed at a rate “never before seen in history.”

As many of them are in politically or physically difficult places, and as capital is short, this looks impossible. Assessing existing fields, the likely rate of discovery and the use of new techniques for extraction, the researchers find that “the peak of world oil production is probably occurring now.”

Are they right? Who knows?

Last month the UK Energy Research Centre published a massive review of all the available evidence on global oil supplies. It found that the date of peak oil would be determined not by the total size of the global resource, but by the rate at which it can be exploited. New discoveries would have to be implausibly large to make a significant difference — even if a field the size of all the oil reserves ever struck in the US were miraculously discovered, it would delay the date of peaking by only four years. As global discoveries peaked in the 1960s, a find like this doesn’t seem very likely.

Regional oil supplies have peaked when about one third of the total resource has been extracted — this is because the rate of production falls as the remaining oil becomes harder to shift when the fields are depleted. So the assumption in the IEA’s new report, that oil production will hold steady when the global resource has fallen “to around one-half by 2030” looks unsafe.

The UK Energy Research Centre’s review finds that just to keep oil supply at present levels, “more than two thirds of current crude oil production capacity may need to be replaced by 2030 ... At best, this is likely to prove extremely challenging.” There is, it says, “a significant risk of a peak in conventional oil production before 2020.”

Unconventional oil won’t save us — even a crash program to develop the Canadian tar sands could deliver only 5 million barrels a day by 2030.

As a report commissioned by the US Department of Energy shows, an emergency program to replace current energy supplies or equipment to anticipate peak oil would need about 20 years to take effect. It seems unlikely that we have it. The world economy is probably knackered, whatever we might do now, but at least we could save farming.

There are two possible options — either the mass replacement of farm machinery or the development of new farming systems, which don’t need much labor or energy.

There are no obvious barriers to the mass production of electric tractors and combine harvesters — the weight of the batteries and an electric vehicle’s low-end torque are both advantages for tractors. A switch to forest gardening and other forms of permaculture is trickier, especially for producing grain, but such is the scale of the creeping emergency that we can’t afford to rule anything out.

The challenge of feeding 7 billion or 8 billion people while oil supplies are falling is stupefying. It’ll be even greater if governments keep pretending that it isn’t going to happen.

There is much evidence that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is sending soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to support Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — and is learning lessons for a future war against Taiwan. Until now, the CCP has claimed that they have not sent PLA personnel to support Russian aggression. On 18 April, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelinskiy announced that the CCP is supplying war supplies such as gunpowder, artillery, and weapons subcomponents to Russia. When Zelinskiy announced on 9 April that the Ukrainian Army had captured two Chinese nationals fighting with Russians on the front line with details

On a quiet lane in Taipei’s central Daan District (大安), an otherwise unremarkable high-rise is marked by a police guard and a tawdry A4 printout from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs indicating an “embassy area.” Keen observers would see the emblem of the Holy See, one of Taiwan’s 12 so-called “diplomatic allies.” Unlike Taipei’s other embassies and quasi-consulates, no national flag flies there, nor is there a plaque indicating what country’s embassy this is. Visitors hoping to sign a condolence book for the late Pope Francis would instead have to visit the Italian Trade Office, adjacent to Taipei 101. The death of

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), joined by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), held a protest on Saturday on Ketagalan Boulevard in Taipei. They were essentially standing for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which is anxious about the mass recall campaign against KMT legislators. President William Lai (賴清德) said that if the opposition parties truly wanted to fight dictatorship, they should do so in Tiananmen Square — and at the very least, refrain from groveling to Chinese officials during their visits to China, alluding to meetings between KMT members and Chinese authorities. Now that China has been defined as a foreign hostile force,

On April 19, former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) gave a public speech, his first in about 17 years. During the address at the Ketagalan Institute in Taipei, Chen’s words were vague and his tone was sour. He said that democracy should not be used as an echo chamber for a single politician, that people must be tolerant of other views, that the president should not act as a dictator and that the judiciary should not get involved in politics. He then went on to say that others with different opinions should not be criticized as “XX fellow travelers,” in reference to