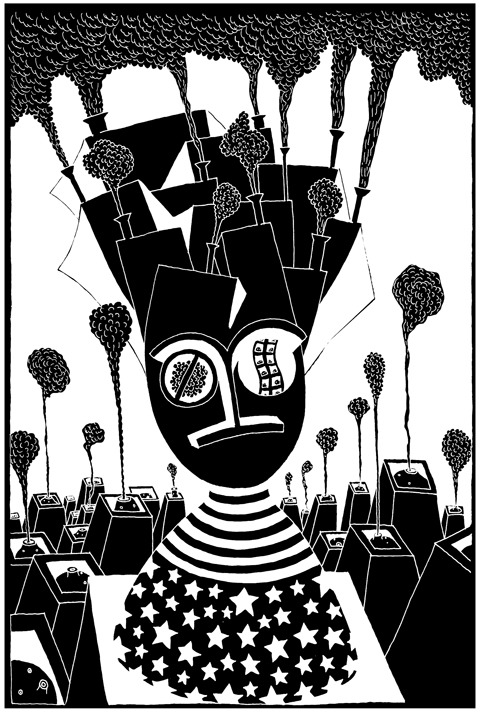

Climate change is happening faster than we believed only two years ago. Continuing with business as usual almost certainly means dangerous, perhaps catastrophic, climate change during the course of this century. This is the most important challenge for this generation of politicians.

I am now very concerned about the prospects for Copenhagen. The negotiations are dangerously close to deadlock at the moment — and such a deadlock may go far beyond a simple negotiating stand-off that we can fix next year. It risks being an acrimonious collapse, perhaps on the basis of a deep split between the developed and developing countries. The world cannot afford such a disastrous outcome.

So I hope that as world leaders peer over the edge of the abyss in New York and Pittsburgh this week, we will collectively conclude that we have to play an active part in driving the negotiations forward.

Now is not the time for playing poker. Now is the time for putting offers on the table, offers at the outer limits of our political constraints. That is exactly what Europe has done, and will continue to do.

Part of the answer lies in identifying the heart of the potential bargain that might yet bring us to a successful result, and it is here, I think, that the world leaders gathering here in New York can make a real difference.

The first part of the bargain is that all developed countries need to clarify their plans on mid-term emissions reductions and show the necessary leadership, not least in line with our responsibilities for past emissions. If we want to achieve at least an 80 percent reduction by 2050, developed countries must strive to achieve the necessary collective 25 percent to 40 percent reductions by 2020. The EU is ready to go from 20 percent to 30 percent if others make comparable efforts.

Second, developed countries must now explicitly recognize that we will all have to play a significant part in helping to finance mitigation action by developing countries. Our estimate is that by 2020, developing countries will need roughly an additional 100 billion euros (US$150 billion) a year to tackle climate change. Part of it will be financed from economically advanced developing countries themselves. The biggest share should come from the carbon market — if we have the courage to set up an ambitious global scheme.

But some will need to come in flows of public finance from developed to developing countries, perhaps from 22 billion euros to 50 billion euros a year by 2020.

Depending on the outcome of international burden-sharing discussions, the EU’s share of that could be anything from 10 percent to 30 percent, that is, up to 15 billion euros a year.

We will need to be ready, in other words, to make a significant contribution in the medium term, and also to look at short term “start-up funding” for developing countries in the next year or so. I look forward to discussing this with EU leaders when we meet at the end of next month.

So we need to signal our readiness to talk finance this week. The counterpart is that developing countries, at least the economically advanced among them, have to be much clearer on what they are ready to do to mitigate carbon emissions as part of an international agreement.

They are already putting domestic measures in place to limit carbon emissions, but they clearly need to step up such efforts — particularly the most advanced developing countries. They understandably stress that the availability of carbon finance from the rich world is a prerequisite to mitigation action on their part, as indeed agreed to in Bali. But the developed world will have nothing to finance if there is no commitment to action.

We have less than 80 calendar days to go until Copenhagen. As with the Bonn meeting last month, the draft text contains some 250 pages: a feast of alternative options, a forest of square brackets. If we don’t sort this out, it risks becoming the longest and most global suicide note in history.

This week in New York and Pittsburgh promises to be a pivotal one, if only for revealing how much global leaders are ready to invest in these negotiations and to push for a successful outcome. The choice is simple: no money, no deal. But no action? Then no money!

Copenhagen is a critical occasion to shift, collectively, to an emissions trajectory that keeps global warming below 2°C. So the fightback has to begin this week in New York.

Jose Manuel Barroso is president of the European Commission.

There is much evidence that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is sending soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to support Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — and is learning lessons for a future war against Taiwan. Until now, the CCP has claimed that they have not sent PLA personnel to support Russian aggression. On 18 April, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelinskiy announced that the CCP is supplying war supplies such as gunpowder, artillery, and weapons subcomponents to Russia. When Zelinskiy announced on 9 April that the Ukrainian Army had captured two Chinese nationals fighting with Russians on the front line with details

On a quiet lane in Taipei’s central Daan District (大安), an otherwise unremarkable high-rise is marked by a police guard and a tawdry A4 printout from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs indicating an “embassy area.” Keen observers would see the emblem of the Holy See, one of Taiwan’s 12 so-called “diplomatic allies.” Unlike Taipei’s other embassies and quasi-consulates, no national flag flies there, nor is there a plaque indicating what country’s embassy this is. Visitors hoping to sign a condolence book for the late Pope Francis would instead have to visit the Italian Trade Office, adjacent to Taipei 101. The death of

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), joined by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), held a protest on Saturday on Ketagalan Boulevard in Taipei. They were essentially standing for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which is anxious about the mass recall campaign against KMT legislators. President William Lai (賴清德) said that if the opposition parties truly wanted to fight dictatorship, they should do so in Tiananmen Square — and at the very least, refrain from groveling to Chinese officials during their visits to China, alluding to meetings between KMT members and Chinese authorities. Now that China has been defined as a foreign hostile force,

On April 19, former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) gave a public speech, his first in about 17 years. During the address at the Ketagalan Institute in Taipei, Chen’s words were vague and his tone was sour. He said that democracy should not be used as an echo chamber for a single politician, that people must be tolerant of other views, that the president should not act as a dictator and that the judiciary should not get involved in politics. He then went on to say that others with different opinions should not be criticized as “XX fellow travelers,” in reference to