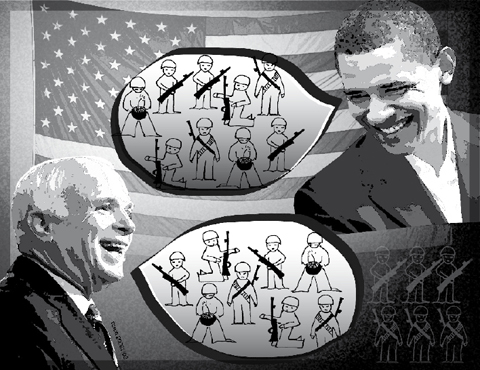

The positions of Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama and Republican rival John McCain on Iraq and Afghanistan probably will not stand the test of reality on crucial foreign policy issues that promise to tangle and vastly complicate the next president’s job, no matter who wins.

Obama says the Iraq War was a blunder from the outset and must be ended quickly, within 16 months of taking office, to free US forces for an intensified fight against the Taliban and its al-Qaeda allies in Afghanistan and neighboring Pakistan. McCain backed the Iraq War at its inception and wants to keep US forces there in pursuit of victory, although what that entails is ill-defined.

Both candidates say more troops are needed in Afghanistan, where violence has increased dramatically. Obama says he would send an additional force of 7,000. McCain does not say how many troops should be added.

The next president’s maneuvering room, however, will be limited by a vast array of complicated unknowns. Chief among them is stiff opposition in Iraq’s parliament to a draft agreement between Washington and the Baghdad government that specifies that US troops leave Iraqi cities by the end of June and withdraw from the country by the end of 2011, unless the government asks them to stay.

The agreement, now seen as unlikely to pass Iraq’s parliament by year’s end, is designed to replace the UN resolution under which US forces invaded Iraq and are allowed to be in the country.

The bilateral pact became necessary after Iraq said it would no longer seek annual renewal of the UN resolution for next year.

US Ambassador Ryan Crocker said he has told Iraqis that US forces will pull back to bases on Jan. 1 if the agreement is not approved by the year-end deadline.

The administration of US President George W. Bush has warned of “real consequences” if Americans are not able to operate there.

“There will be no legal basis for us to continue operating there without that,” White House Press Secretary Dana Perino said. “And the Iraqis know that. And so, we’re confident that they’ll be able to recognize this.”

McCain, for his part, insists that the so-called Status of Forces agreement is condition-based, his term for gauging whether US forces can be drawn down.

But when asked directly if he would honor the agreement, McCain said: “I’ve always said we could be out based on conditions, and honor and victory, and not defeat.”

What precisely the conditions would be are not clear and there’s plenty of wiggle room in such a response.

For Obama, the agreement, if it goes into force, comes closer to what he has been proposing all along. His 16-month deadline for pulling out US troops would expire in May of 2010. But that still is more than a year and a half before what is called for in the pending US-Iraqi agreement. He also wants to leave in place a US presence of unspecified size that would continue with training Iraqi forces, protecting US diplomats and other interests and standing by as a rapid-response force in case of a significant resurgence of violence. That position leaves him room for maneuver as well.

Early on, the Iraq War, and the Afghan conflict to a lesser degree, promised to dominate the US election, forcing both Obama and McCain to set out hard positions on what was then seen as the defining issue in their White House contest.

In the meantime, the economy stumbled under the weight of the home mortgage crisis that, in the final two months of the campaign, spawned the most unnerving financial and economic turmoil to face the country since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

But with the wars having cost a minimum of US$800 billion, leaving aside a US death toll approaching 5,000 and tens of thousands of civilian Iraqi deaths, the conflicts remain — even if overshadowed by economic news — a huge financial and moral drag on the US. A majority of Americans no longer back the Iraq conflict.

Also, while the extraordinary sectarian violence that shattered Iraq has been tamped down, the centuries-long estrangement of Sunni and Shiite Muslims remains and is most likely to flare again with the departure of US forces. Kurdish desires for autonomy in the north of the country only complicate the seemingly intractable divide in the Arab majority.

Iraqi security forces — while larger in number, better trained and less beholden to one sect or another — remain unprepared to take over keeping the peace. Most military analysts do not believe they will be ready for that job by Obama’s 16-month pullout deadline.

That means the departure of US forces would leave innocent Iraqis vulnerable to intensified bloodshed and misery well beyond the existing difficulties of just getting by in a country with a fractured infrastructure and failed economy.

Iraq’s leaders still have not agreed on a law to divide the country’s massive oil wealth among Sunni and Shiite Arabs and the Kurds. Nor is there resolution over potentially explosive Kurdish demands for control of the city of Kirkuk and the oil-rich region surrounding it. Failure to pass the so-called oil law produced a US$79 billion surplus but no mechanism to distribute the wealth among the beleaguered citizenry.

Millions of Iraqis have fled their homes and remain in internal exile or outside the country. The corps of the most educated Iraqis — physicians, engineers, college professors and teachers — have left the country.

The government of Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki is weak, with little administrative reach beyond Baghdad.

In the face of those realities, Obama argues that setting a troop pullout deadline will focus the Iraqis on solving their own problems instead of relying on the Americans. What’s more, he says, keeping US forces locked in Iraq has allowed militants in Afghanistan, where he contends the danger to US security is far greater, to regroup and threaten the undeniably weak pro-US government of Afghan President Hamid Karzai.

McCain, meanwhile, has a strong argument that a US departure now could reignite the chaos that gripped the country until the second half of last year. While the Arizona senator bases his position on matters of US honor and national security, Iraq does remain highly unstable, its people deeply vulnerable.

Both candidates might want to remember that Bush railed against nation-building before winning the 2000 White House contest.

Then came Iraq, and the US was dragged into one of the largest such projects in US history.

There is much evidence that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is sending soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to support Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — and is learning lessons for a future war against Taiwan. Until now, the CCP has claimed that they have not sent PLA personnel to support Russian aggression. On 18 April, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelinskiy announced that the CCP is supplying war supplies such as gunpowder, artillery, and weapons subcomponents to Russia. When Zelinskiy announced on 9 April that the Ukrainian Army had captured two Chinese nationals fighting with Russians on the front line with details

On a quiet lane in Taipei’s central Daan District (大安), an otherwise unremarkable high-rise is marked by a police guard and a tawdry A4 printout from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs indicating an “embassy area.” Keen observers would see the emblem of the Holy See, one of Taiwan’s 12 so-called “diplomatic allies.” Unlike Taipei’s other embassies and quasi-consulates, no national flag flies there, nor is there a plaque indicating what country’s embassy this is. Visitors hoping to sign a condolence book for the late Pope Francis would instead have to visit the Italian Trade Office, adjacent to Taipei 101. The death of

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), joined by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), held a protest on Saturday on Ketagalan Boulevard in Taipei. They were essentially standing for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which is anxious about the mass recall campaign against KMT legislators. President William Lai (賴清德) said that if the opposition parties truly wanted to fight dictatorship, they should do so in Tiananmen Square — and at the very least, refrain from groveling to Chinese officials during their visits to China, alluding to meetings between KMT members and Chinese authorities. Now that China has been defined as a foreign hostile force,

On April 19, former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) gave a public speech, his first in about 17 years. During the address at the Ketagalan Institute in Taipei, Chen’s words were vague and his tone was sour. He said that democracy should not be used as an echo chamber for a single politician, that people must be tolerant of other views, that the president should not act as a dictator and that the judiciary should not get involved in politics. He then went on to say that others with different opinions should not be criticized as “XX fellow travelers,” in reference to