“Give me half a tanker of iron, and I will give you an ice age,” late US oceanographer John Martin once said.

The inflammatory comment alluding to geological records that suggest there were high levels of iron in the ocean during the glaciations was never likely to win prizes for making friends and influencing people.

Martin’s “iron hypothesis,” put forward in the early 1990s, suggested seeding plankton-low areas of ocean in order to hotwire the so-called biological pump — a naturally occurring phenomenon that sequesters carbon dioxide on the seabed.

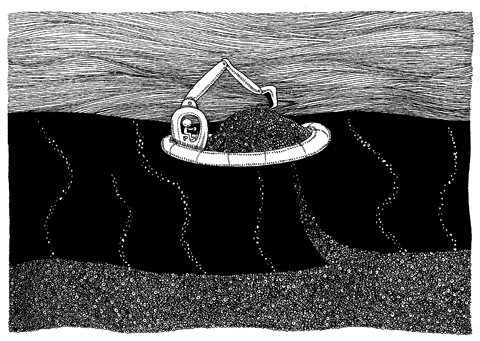

ILLUSTRATION: MOUNTAIN PEOPLE

His ocean fertilization theory has never had an easy ride. Some researchers argue that it is an inefficient way of capturing and storing carbon dioxide; others say the technology could have disastrous consequences, such as damaging ecosystems, inadvertently releasing more potent greenhouse gases such as methane, or stimulating the growth of toxic algae.

Scientists around the world began to test the idea, adding nutrients, usually iron, to the sea and watching what happened next. But it was not until fairly recently, when commercial companies began taking an interest in exploiting Martin’s idea in order to make money from the carbon market, that the antennae of scientists and environment groups really began to twitch.

Jim Thomas, researcher and writer at the Ottawa-based technology watchdog ETC Group, says: “It is the cheapest way of making carbon credits. Whether you mess up the oceans in the process does not matter to them as long as they can make money out of it.”

The concerns recently prompted a conference of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity to agree a moratorium on commercial ocean fertilization and on all but small-scale, scientifically controlled tests in coastal waters, at least until the technology is properly understood — already dubbed the first global attempt to police geo-engineering.

“Basically, it means nations around the world have agreed they are not going to permit large-scale ocean fertilization to go ahead,” Thomas said. “The work-round is to do small-scale, strictly scientific — not commercial — tests that are not for using or generating carbon credits.”

The biological pump itself is quite elegant. Phytoplankton, a kind of microscopic marine plant, at or near the ocean’s surface convert carbon dioxide into organic matter and oxygen and when they die carry small amounts carbon to the seabed, where it is stored in sediments for millions of years.

There is a physical pump too, where carbon dioxide dissolves in the ocean at high latitudes, is pulled down by sinking currents and stays there for hundreds of years before returning to the surface. Exploiting the latter by piping liquid carbon dioxide directly into the deep ocean has also been proposed, a different technology to ocean fertilization but one that has provoked many similar concerns.

Victor Smetacek, professor of biological oceanography at the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany, was chief scientist on the European iron fertilization experiment — the most recent and most thorough of about a dozen major ocean fertilization tests. Three tonnes of iron sulphate — made from powder you can buy at garden centers to treat lawns — was poured from the research vessel Polarstern into a 150km2 eddy in the southern ocean.

A bloom of phytoplankton occurred almost immediately, as expected. What surprised the scientists was the discovery four weeks later of a vast amount of dead and dying matter from their man-made bloom, sinking extraordinarily quickly.

It was something nobody had properly witnessed before and, as Smetacek said, “one of nature’s mechanisms to regulate carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and ultimately global climate.”

The results are so far unpublished but Smetacek said a “significant amount” of carbon sank with the dying bloom.

“There is no question our bloom behaved the way blooms are supposed to behave, they build up and then they sink. We found it sinking down the water column and all the previous experiments did not find that. I am of the opinion that you cannot afford not to do it, iron fertilization. On the other hand, the outstanding question is who is going to do it? Is somebody going to make a profit out of it? I think this is too important to be left to the mercy of the profit-makers,” he said.

In about a third of the oceans — the so-called paradoxical zones — the growth of phytoplankton is limited by lack of iron, a nutrient essential for life. Adding iron to a quarter of the world’s seas, in areas where amounts of the mineral are low, would, proponents say, remove about 1 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide a year from the atmosphere — roughly 15 percent of what accumulates annually because of human activity.

“If you get it wrong on that scale, things could be a bit serious,” said Chris Vivian, chair of the Scientific Group of the London Convention, which regulates dumping waste at sea and has issued its own “statement of concern” about ocean fertilization.

“If we wanted to have an impact, we would probably have to do something on that scale. And if it worked, we would have to do this continuously, year after year after year. It is a continuous activity, which is another concern.”

The moratorium is not a legal instrument and cannot be enforced, although countries usually respect the UN convention’s decisions.

Southern countries, whose seas have been targeted for commercial trials, were the most vocal in favor of a moratorium, supported by European nations. Worryingly for some, the US, home to the most gung-ho commercial ocean fertilization companies, is not a signatory to the convention.

Margaret Leinen, chief scientist at Climos, a company that aims to use sea power to fight climate change, said the UN convention requested that governments exercise precaution and ensure further tests are controlled, rather than specifying an outright suspension.

“They did not impose a moratorium, they identified conditions that they thought should be met,” she said. “We have no disagreements with this call for scientific justification, an analysis of risk and regulatory control.”

“Small-scale” is expected to be defined at about the size of previous experiments: 100km2 to 200km2.

San Francisco-based Climos, the leading commercial ocean fertilization company, has proposed testing an area of 40,000km2. Already, some scientific groups have criticized the prohibition of large-scale trials, arguing it puts too strict a restriction on research.

David Santillo, senior scientist at Greenpeace International’s research laboratory in Exeter, says: “It would be like doing an experiment in a laboratory with no ceiling, no walls and no floor. If something goes wrong, there is very little they could do, even if they could discover something had gone wrong in the first place.

“What they have come up with in terms of the moratorium is quite reasonable. What they have said is that there should be no pursuit of this, except small-scale experiments ... which stops some of the more aggressive commercial exploitation of this and lets some experiments proceed,” he said.

If Martin were still alive, he would probably retract his incendiary comment about an ice age. Many would not. For the latter, the moratorium on ocean fertilization is an important first step towards trying to control geo-engineered, sometimes science fiction-like, attempts to solve the climate crisis.

There is much evidence that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is sending soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to support Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — and is learning lessons for a future war against Taiwan. Until now, the CCP has claimed that they have not sent PLA personnel to support Russian aggression. On 18 April, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelinskiy announced that the CCP is supplying war supplies such as gunpowder, artillery, and weapons subcomponents to Russia. When Zelinskiy announced on 9 April that the Ukrainian Army had captured two Chinese nationals fighting with Russians on the front line with details

On a quiet lane in Taipei’s central Daan District (大安), an otherwise unremarkable high-rise is marked by a police guard and a tawdry A4 printout from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs indicating an “embassy area.” Keen observers would see the emblem of the Holy See, one of Taiwan’s 12 so-called “diplomatic allies.” Unlike Taipei’s other embassies and quasi-consulates, no national flag flies there, nor is there a plaque indicating what country’s embassy this is. Visitors hoping to sign a condolence book for the late Pope Francis would instead have to visit the Italian Trade Office, adjacent to Taipei 101. The death of

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), joined by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), held a protest on Saturday on Ketagalan Boulevard in Taipei. They were essentially standing for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which is anxious about the mass recall campaign against KMT legislators. President William Lai (賴清德) said that if the opposition parties truly wanted to fight dictatorship, they should do so in Tiananmen Square — and at the very least, refrain from groveling to Chinese officials during their visits to China, alluding to meetings between KMT members and Chinese authorities. Now that China has been defined as a foreign hostile force,

On April 19, former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) gave a public speech, his first in about 17 years. During the address at the Ketagalan Institute in Taipei, Chen’s words were vague and his tone was sour. He said that democracy should not be used as an echo chamber for a single politician, that people must be tolerant of other views, that the president should not act as a dictator and that the judiciary should not get involved in politics. He then went on to say that others with different opinions should not be criticized as “XX fellow travelers,” in reference to