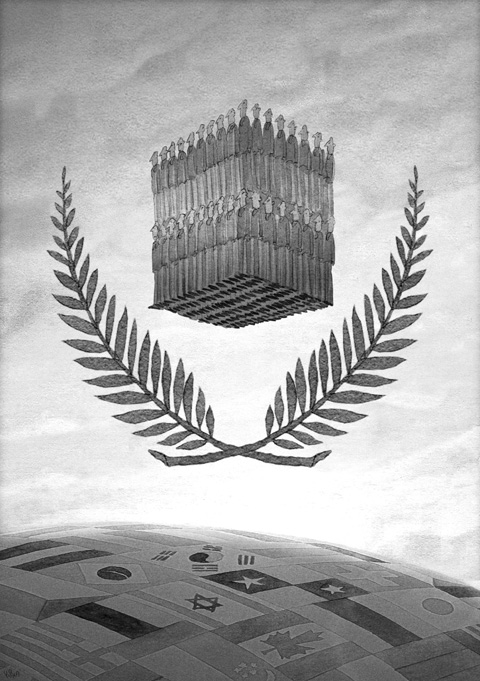

On June 18, the UN’s intergovernmental Human Rights Council took an important step toward eliminating the artificial divide between freedom from fear and freedom from want that has characterized the human rights system since its inception.

By giving the green light to the Optional Protocol to the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Council has established an important mechanism to expose abuses that are typically linked to poverty, discrimination and neglect.

It will now be up to the UN General Assembly to provide final approval of the protocol. If adopted, this instrument can make a real difference in the lives of those who are often left to languish at the margins of society, and who are denied economic, social and cultural rights, such as access to adequate nutrition, health services, housing and education.

Sixty years ago, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognized that freedom from want and freedom from fear are indispensable preconditions for a dignified life. The declaration unequivocally linked destitution and exclusion with discrimination and unequal access to resources and opportunities. Its framers understood that social and cultural stigmatization precludes full participation in public life and the ability to influence policies and obtain justice.

Yet this unified approach was undermined by the post-World War II logic of geopolitical blocs competing over ideas, power and influence. Human rights were also affected by such Cold War bipolarity. Countries with planned economies argued that the need for survival superseded the aspiration to freedom, so that access to basic necessities included in the basket of economic, social and cultural rights should take priority in policy and practice.

By contrast, Western governments were wary of this perspective, which they feared would hamper free-market practices, impose overly cumbersome financial obligations or both. Thus, they chose to prioritize those civil and political rights that they viewed as the hallmarks of democracy.

Against this background, it was impossible to agree on a single, comprehensive human rights instrument giving holistic effect to the declaration’s principles. And unsurprisingly, it took almost two decades before UN member states simultaneously adopted two separate treaties — the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights — encompassing the two distinct baskets of rights. However, only the former treaty was endowed with a follow-up mechanism to monitor its implementation.

In practice, this discrepancy created a category of “alpha” rights — civil and political — that took priority in influential and wealthy countries’ domestic and foreign policy agendas. By contrast, economic, social and cultural rights were often left to linger at the bottom of the national and international “to do” lists.

Addressing this imbalance between the two baskets of rights, the new protocol establishes for the Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights a vehicle to expose abuse, known as a “complaint mechanism,” similar to those created for other core human rights treaties. This procedure may seem opaque, but by lodging a complaint under the protocol’s provisions, victims will now be able to bring to the surface abuses that their governments inflict, fail to stop, ignore or do not redress. In sum the protocol provides a way for individuals, who may otherwise be isolated and powerless, to make the international community aware of their plight.

After its adoption by the General Assembly, the protocol will enter into force when a critical mass of UN member states has ratified it. This should contribute to the development of appropriate human rights-based programs and policies enhancing freedoms and welfare for individuals and their communities.

Not all countries will embrace the protocol. Some will prefer to avoid any strengthening of economic, social and cultural rights and will seek to maintain the status quo. The better and fairer position, however, is to embrace the vision of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and promote unambiguously the idea that human dignity requires respect for the equally vital and mutually dependent freedoms from fear and want.

Louise Arbour is UN high commissioner for human rights.

COPYRIGHT: PROJECT SYNDICATE

The US Senate’s passage of the 2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which urges Taiwan’s inclusion in the Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercise and allocates US$1 billion in military aid, marks yet another milestone in Washington’s growing support for Taipei. On paper, it reflects the steadiness of US commitment, but beneath this show of solidarity lies contradiction. While the US Congress builds a stable, bipartisan architecture of deterrence, US President Donald Trump repeatedly undercuts it through erratic decisions and transactional diplomacy. This dissonance not only weakens the US’ credibility abroad — it also fractures public trust within Taiwan. For decades,

The government and local industries breathed a sigh of relief after Shin Kong Life Insurance Co last week said it would relinquish surface rights for two plots in Taipei’s Beitou District (北投) to Nvidia Corp. The US chip-design giant’s plan to expand its local presence will be crucial for Taiwan to safeguard its core role in the global artificial intelligence (AI) ecosystem and to advance the nation’s AI development. The land in dispute is owned by the Taipei City Government, which in 2021 sold the rights to develop and use the two plots of land, codenamed T17 and T18, to the

The ceasefire in the Middle East is a rare cause for celebration in that war-torn region. Hamas has released all of the living hostages it captured on Oct. 7, 2023, regular combat operations have ceased, and Israel has drawn closer to its Arab neighbors. Israel, with crucial support from the United States, has achieved all of this despite concerted efforts from the forces of darkness to prevent it. Hamas, of course, is a longtime client of Iran, which in turn is a client of China. Two years ago, when Hamas invaded Israel — killing 1,200, kidnapping 251, and brutalizing countless others

Taiwan’s first case of African swine fever (ASF) was confirmed on Tuesday evening at a hog farm in Taichung’s Wuci District (梧棲), trigging nationwide emergency measures and stripping Taiwan of its status as the only Asian country free of classical swine fever, ASF and foot-and-mouth disease, a certification it received on May 29. The government on Wednesday set up a Central Emergency Operations Center in Taichung and instituted an immediate five-day ban on transporting and slaughtering hogs, and on feeding pigs kitchen waste. The ban was later extended to 15 days, to account for the incubation period of the virus