The order by US President George W. Bush for the Navy to launch an anti-missile interceptor to destroy a disabled satellite before it falls from orbit carries opportunity, but also potential embarrassment, for the administration and advocates of its missile defense program.

The decision was described by senior officials as designed solely to protect populated areas from space debris, and not to showcase how the emerging missile defense arsenal can be reprogrammed to counter an unexpected threat: in this case, hazardous rocket fuel aboard the dead satellite.

Even so, the attempt, expected within the next two weeks, will again throw into sharp relief the administration's antipathy to treaties limiting anti-satellite weapons, which puts the US opposite China and Russia, which just last week proposed a new pact banning space weapons.

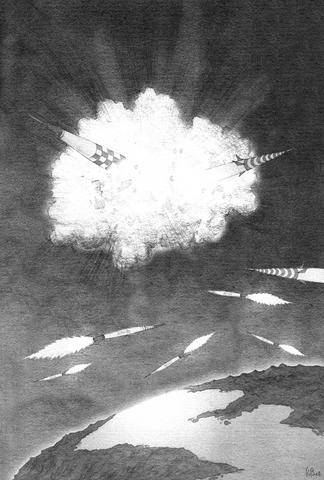

Often compared to hitting a bullet with a bullet, the shooting down of ballistic missiles with an interceptor rocket is difficult, as an adversary's warheads would be launched unexpectedly on relatively short arcs -- and most likely more than one at a time.

So it should be easier for the Navy's Standard Missile 3, launched from an AEGIS cruiser in the northern Pacific, to find and strike a satellite almost the size of a school bus making orbits almost as regular as bus routes around the globe, 16 times a day.

Should it succeed, the accomplishment would embolden those who champion even more spending on top of the US$57.8 billion appropriated by Congress for missile defense since the Bush administration's first budget in the 2002 fiscal year.

It might even revive a dormant effort to focus the military on anti-satellite operations, as well. Failure, on the other hand, would be cited as hard and fresh evidence for those who point to the futility of space-warfare programs.

Beyond arguments over whether anti-missile weapons also provide thinly cloaked anti-satellite capabilities, and Russia's caustic opposition to building US missile defense bases in Poland and the Czech Republic, the highly unusual mission to destroy a US spy satellite has highlighted what historically was a sideshow of superpower nuclear arms control negotiations, the question of whether to ban space weapons altogether.

The US is perhaps the nation most dependent on satellites, both for commerce and for military communications, reconnaissance and targeting. And, to be sure, the Bush administration was harshly critical when the Chinese launched an anti-satellite missile last year, the first time any nation had blasted an object in space in the 22 years since the US last conducted such a test.

At the same time, however, the US has resisted suggestions that a new arms-control regime be negotiated to govern space weapons, and has asserted its sovereign right to defend its own access to space and to deny it to others in future wars.

"The administration places a higher priority on military flexibility and does not want to constrain military options," said Michael Krepon, cofounder of the Henry L. Stimson Center, an arms-control advocacy organization.

That assessment is not refuted by White House officials.

"The United States is committed to preserving equal access to space for peaceful purposes," a White House spokesman, Scott Stanzel, said on Friday. "At the same time, we oppose the creation of legal regimes or other international agreements that seek to limit or prohibit our use of space."

Stanzel noted that previous administrations opposed similar treaties, in part, he said, because they are hard to verify and police, since any object in space, even debris from a destroyed satellite, can act as a weapon.

During the Cold War, the US and the Soviet Union conducted about 50 anti-satellite tests: a significant number, but small compared to the 2,000 nuclear weapons tests carried out in that same period of superpower arms races.

Efforts to ban space weapons, like the treaty proposed by China and Russia, are generally favored by arms-control analysts, even though they view the latest such initiative as deeply flawed.

During a session of the Conference on Disarmament last week in Geneva, China and Russia proposed a new pact that would go beyond the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, which bans orbiting weapons of mass destruction, and would prohibit all weapons in space.

Krepon said the problem with the new proposal, a hindrance that has bedeviled previous efforts, is how to define a weapon.

For example, lasers can be used harmlessly for determining distances in space and gathering information on objects in space, as well as for beaming communications back to Earth, but also can be used as weapons.

Similarly, debris from a decaying object in space, a satellite for example, can be as dangerous to other platforms in space as a missile fired from Earth.

The new proposal, by focusing on weapons in space, also "does not cover ground and sea-based means that could be used to harm satellites, such as the Chinese ground-based anti-satellite weapon tested a year go," Krepon said.

Despite renewed interest in anti-satellite weaponry sparked by Thursday's announcement in Washington, the reaction from Beijing and Moscow thus far has been muted.

Additional reporting by Steven Lee Myers

The government and local industries breathed a sigh of relief after Shin Kong Life Insurance Co last week said it would relinquish surface rights for two plots in Taipei’s Beitou District (北投) to Nvidia Corp. The US chip-design giant’s plan to expand its local presence will be crucial for Taiwan to safeguard its core role in the global artificial intelligence (AI) ecosystem and to advance the nation’s AI development. The land in dispute is owned by the Taipei City Government, which in 2021 sold the rights to develop and use the two plots of land, codenamed T17 and T18, to the

Taiwan’s first case of African swine fever (ASF) was confirmed on Tuesday evening at a hog farm in Taichung’s Wuci District (梧棲), trigging nationwide emergency measures and stripping Taiwan of its status as the only Asian country free of classical swine fever, ASF and foot-and-mouth disease, a certification it received on May 29. The government on Wednesday set up a Central Emergency Operations Center in Taichung and instituted an immediate five-day ban on transporting and slaughtering hogs, and on feeding pigs kitchen waste. The ban was later extended to 15 days, to account for the incubation period of the virus

The ceasefire in the Middle East is a rare cause for celebration in that war-torn region. Hamas has released all of the living hostages it captured on Oct. 7, 2023, regular combat operations have ceased, and Israel has drawn closer to its Arab neighbors. Israel, with crucial support from the United States, has achieved all of this despite concerted efforts from the forces of darkness to prevent it. Hamas, of course, is a longtime client of Iran, which in turn is a client of China. Two years ago, when Hamas invaded Israel — killing 1,200, kidnapping 251, and brutalizing countless others

Art and cultural events are key for a city’s cultivation of soft power and international image, and how politicians engage with them often defines their success. Representative to Austria Liu Suan-yung’s (劉玄詠) conducting performance and Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen’s (盧秀燕) show of drumming and the Tainan Jazz Festival demonstrate different outcomes when politics meet culture. While a thoughtful and professional engagement can heighten an event’s status and cultural value, indulging in political theater runs the risk of undermining trust and its reception. During a National Day reception celebration in Austria on Oct. 8, Liu, who was formerly director of the