With the right flight connections, a journey from the 21st century to the 14th century can take just over 12 hours. It begins in the hot, crowded duty-free hell of Heathrow's Terminal 3 and ends -- through the bushes down a snaking mud track -- by the marshes under a cloudless blue African sky.

In front of us five women are doing what the women in these parts have done for thousands of years -- fetching water for evening cooking and washing.

Dressed in luminous greens and pinks, they return with their heavy yellow cans and hoist them on their heads for the long trail back to their huts.

A few minutes later we're in an African village straight from the pages of childhood story books. Half a dozen mud and thatched houses circle an ever-changing cast of clucking hens, goats and children. There is no sound apart from the chickens and chatter of voices, young and old.

This is Katine, in northern Uganda, which for the next three years will be the center of a unique experiment between the Guardian newspaper, its readership, a bank and a non-governmental organization (NGO).

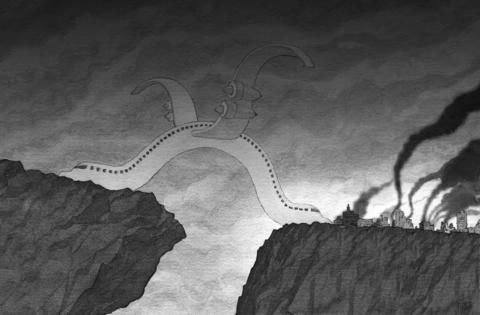

Together, we're going to try to help the people who live here to make a significant difference -- harnessing the power of 21st century communications, expertise, resources and good will to help change lives still trapped in the 14th century.

The centurial metaphor is from the Oxford economist Paul Collier, who has spent a lifetime studying Africa. In his recent book he writes of the world's bottom billion, who "coexist with the 21st century, but their reality is the 14th century: civil war, plague, ignorance." Katine has had its fair share of all three.

Our experiment will not be uncontroversial. Little to do with aid or development is.

The first, and most obvious, question is: Why intervene at all in a way of life that has changed little in hundreds of years? It is a troubling question that niggles away throughout our visit. There will be plenty of people -- on both the left and right of the development argument -- who may ask: Why Katine? Or even: Why bother?

choosing katine

The answer for me began to harden as I spoke to one of the women collecting the water in that idyllic-seeming scene I'd just witnessed, hot off the plane.

She turned out to be called Joyce Abuko, a 30-year-old mother of five children who also looks after three children of her husband's co-wife and four more children orphaned by AIDS.

So 12 lives in all depend on Joyce. They depend on her rising early in the single mud-floored room she shares with some of the children, some of the chickens, her cooking pans and her food. Twelve lives depend on her cooking, gardening, cleaning, fetching and carrying. They depend on her for their health, their education and their security. They need her to be strong and in good health.

But the odds are heavily stacked against Joyce. Start with the water. The borehole she and her friends use has been swamped by the catastrophic floods that have hit central and eastern Africa this year, displacing up to 300,000 Ugandans -- very probably the result of climate change caused by the affluent other world of which Joyce has no knowledge or conception.

disease

The swamps are host to malaria, schistosomiasis and jigger worms, which burrow into human skin and can cause secondary infections, including tetanus and gangrene. Joyce confesses she is too tired -- and, anyway, doesn't have enough time in her day -- to boil the water before her children drink and wash in it. I could only find evidence of one, hole-ridden, malaria net.

So, sooner or later, Joyce and those in her care will end up in the local health center. At first glance it looks impressive enough: a series of long brick huts, even an operating theater.

But, as with so much about Katine, appearances are deceptive. There is no electricity or running water, few malaria nets and an inadequate supply of drugs. The operating theater, opened with some ceremony by Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni's wife a year ago, has never been used.

On the day we visited, the place had a feeling of hopelessness and decay about it. A solitary ambulance stood unused in the long grass, waiting for spare parts. A charcoal stove was the only way of sterilizing equipment in the delivery room; a single paraffin lamp was the only means of light after dark. Medical recordkeeping was rudimentary, with only a quarter of the local population tested for HIV.

Government figures suggest that Joyce will be lucky to live beyond 46. She has a one in four chance of dying from malaria.

Joyce's brood stand little opportunity of improving their lot through education. They travel long distances to get to school by 7:30am. There is no food for the children during the day. By mid-morning, even those who came have begun to drift off home.

Sanitation is poor -- five holes in the ground for a notional roll of 650 children -- and no water. Girls stay at home when menstruating and many drop out early because of pregnancy or marriage.

As at the hospital, there was a forlorn air about the Katine primary school the day we called in. The teacher who greeted us was initially upbeat and welcoming. But as she recited a litany of problems -- few text books, classes of up to 130, poor accommodation for teachers and so on -- the life sagged out of her. I watched as a class of listless 10-year-olds struggled with an aimless lesson in creationism.

There was more spirit up the road at the local community primary school -- started by a group of parents -- but with even more basic conditions. Children sat on mud floors or rough hewn logs under grass roofs open to rain. The sum total of written texts amounted to seven Bibles. The seven teachers (between 350 children) wrote in the dust for lack of slates.

So much for plague and ignorance. The last in Paul Collier's trilogy of 14th-century disasters -- civil war -- has also been visited on Katine. Of the two main rebel groups operating in northern Uganda, the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) has wreaked the most havoc -- looting, raping, mutilating and killing numerous residents and abducting countless thousands of children in the name of the religious fanatic, Joseph Kony.

kidnapped

I met one young man -- still worried about giving his full name -- who had found his way back to Katine after a year of abduction. He had been kidnapped at 17 and spent a year of forced marches, sometimes roped to hundreds of other young men. He described how they had looted their way across the country. He spoke of seeing numerous killings; of ears and hands sliced off; of friends branded with red hot pangas; of raids on terrorized farmers and terrifying battles with the Ugandan army.

As many as 5,000 refugees from neighboring areas established a displaced persons camp in Katine in 2003, placing further strain on the local infrastructure, even further weakened by the LRA cutting the power supply, which has never been reconnected. There are still 250 people living in the camp, too terrified to return to their homes.

Janet Adwo, 24, showed me inside the cramped hut that has been home for her and her two children for four years -- all of them sleeping on a rag mattress with no mosquito net. In a nearby hut a 65-year-old man sucking ajon (millet-based hooch) through a hollow twig told of the calamities he had lived through recently.

He fiercely rounded on a pair of laughing girls.

"There are things I do not like to speak of in their presence," he said. "Young children killed by bamboo sticks pushed through their anuses."

The girls fell silent.

The area has also been subject to repeated raids from the Karamajong tribesmen, armed with AK-47s, who rounded up and stole all the cattle they could find. Farmers have had to fall back on crop production, but with negligible markets for their food.

So, that is life in Katine. These are people with almost nothing bar the clothes they stand up in and the patchy grass roofs over their heads. They are living on fine margins between a hard life and early death.

But for all this hardship and misery, Katine does not feel like a hopeless society -- far from it. The community is full of heroines like Joyce. It is impossible not to be struck by an immense warmth and resilience ... and a fierce ambition to do better.

It is quite hard to see how this "sub-county" -- we are talking of a dispersed community of about 20,000 people -- is going to do better on its own.

Development economists have their varying theories to explain how countries such as Uganda and places such as Katine end up so desperately poor. Malaria, physical geography, poor governance, fiscal failure, trade and conflict are among the standard explanations -- all of them applicable to Katine.

Collier would also point to Uganda being landlocked between Kenya, itself stagnant for 30 years; Sudan, gripped by civil war; Rwanda, devastated by genocide; Somalia, which simply collapsed; the Congo, laid low by years of catastrophic conflict; and Tanzania, which invaded it.

He is also clear that in seeking to help places such as Katine we cannot rescue them.

"The societies of the bottom billion can only be rescued from within," he writes. "In every society of the bottom billion there are people working for change, but usually they are defeated by powerful internal forces stacked against them. We should be helping the heroes. So far, our efforts have been paltry: through inertia, ignorance, and incompetence, we have stood by and watched them lose."

"A future world with a billion people living in impoverished and stagnant countries is just not a scenario we can countenance. A cesspool of misery next to a world of growing prosperity is both terrible for those in the cesspool and dangerous for those who live next to it. We had better do something about it. The question is what," he writes.

The question is what: Most Western journalists periodically scratch their heads about how to keep some subjects fresh, including poverty and climate change. The big picture is known; the facts change little from day to day. Such subjects are at once the biggest news of our times -- and not news at all.

beyond christmas

Would it be possible to find a way of dramatizing an issue so that it held attention beyond Christmas, even for as long as three years? Of connecting the ideas, good will, resources and expert knowledge of millions of readers around the world and focusing them on one problem? Would it be possible to do all this in a way that avoided the trap of creating a temporary oasis in a desert? Of doing something both sustainable and replicable?

Could there be a model for using Web-based technologies -- and the power to link and harness people -- that could be developed by other Western communities, whether businesses, schools or towns? Why twin your village with one in Belgium if you could twin it with one in Uganda?

Such were our thoughts as we sought partners who could translate our ambitions into practical realities. Assorted NGOs came in and pitched their ideas for how such a project might work. It was AMREF (the African Medical & Research Foundation) -- a charity that specializes in Africa and began life in 1957 as the Flying Doctor service -- that came up with the most persuasive ideas.

AMREF, whose staff is 97 percent African, nominated Katine, in the Soroti district of north Uganda, as the community it would most like to work with. The foundation emphasized that the project would only take root if it could be the catalyst for change rather than something imposed from outside. It would take advantage of -- and build on -- existing social and economic networks as well as traditional and indigenous knowledge.

We have been joined by Farm Africa, a vastly experienced NGO accustomed to working with poor African farmers, and Barclays Bank, which has promised more than US$3 million in support (US$2 million of which will match readers' donations) as well as helping out with micro-finance and general economic development.

on the scene

As for the Guardian and the Observer, we have sent a number of writers and photographers to Katine to map and record the area and its people, including health editor Sarah Boseley, environmental editor John Vidal, and Dan Chung, one of the world's leading photojournalists.

Boseley and Chung's detailed report appears in a separate supplement and on the Guardian Web site (www.guardian.co.uk/katine).

It seems to me that a newspaper (and Web operation) can do three things as part of this partnership.

First, it can report, record, explain, contextualize, illuminate and analyze -- all the day-to-day business of journalism. It can explore the complexities of trying to help communities such as Katine in a sustainable way. It should be able to get beyond the sloganeering and occasionally stultifying politics of the development debate.

Second, it can involve a huge community of readers and Web users around the world and find ways of linking them in to what we're doing. We'll need money, obviously. But just as importantly, we'll need advice and involvement. Among our readers are water engineers, doctors, solar energy experts, businesspeople, teachers, nurses and farmers. We don't need a stampede of volunteers, but we would like a bank of people with technical know-how who are prepared to offer time and advice.

pressuring kampala

Finally, it can achieve visibility for (and thus exert pressure on behalf of) Katine. Katine and its problems barely register in Uganda's capital, Kampala. Some local officials worry that because it is an area where the political opposition to Museveni's NRM party is strong, Katine's problems may not have been among the government's highest priorities. That may be unfair, but the fact remains that this is one of the poorest, least developed areas of Uganda.

Now for the hard bit. For a newspaper campaign, three years is a long stretch, but in terms of a sustainable aid project it is relatively short and sharp. Some of the most rooted and important work -- training, reliable information and record keeping, supply systems and so on -- is unglamorous and invisible to the naked eye.

But there will be more obvious, and more easily recordable, progress. We want mosquito nets (thousands of them), bicycles (hundreds of them) and solar panels (dozens of them). We'll need books, footballs, buildings, boreholes, pumps, computers and a lot else. Through the Web site we'll show tangible evidence of progress and keep you in touch with our needs.

no garden of eden

Back to that niggling question: Why intervene? On one level it is a simple question. Here are people within our reach and knowledge whose lives are quite brutally shortened by preventable disease, hunger and ignorance.

They are people with virtually no earthly possessions and no carbon footprint, whose lives are likely to be made harder still by the climate change caused by people infinitely richer in belongings and education. To do nothing is, on this level, unthinkable.

After Joyce had described her average day to me -- a treadmill of fetching, carrying, cooking, cleaning, hoeing, weeding, thrashing and grinding merely to survive -- I asked her what single thing would most improve her life.

She thought for a moment and answered: "I love sitting down with my friends. I would like more time to talk."

Just that, no more.

Katine is no Garden of Eden. But as you brace yourself to elbow your way back through Heathrow Terminal 3, you harbor niggling prelapsarian feelings about what you've just left behind.

So you want Joyce and the 12 children who depend on her to stand a better chance of a life without preventable disease and hunger. You want to help Katine stand on its own two feet and to exist without conflict, displacement and famine. But you also want to move gently and with the greatest possible sensitivity to the culture you have, briefly, witnessed, shared and honored.

There is much evidence that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is sending soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to support Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — and is learning lessons for a future war against Taiwan. Until now, the CCP has claimed that they have not sent PLA personnel to support Russian aggression. On 18 April, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelinskiy announced that the CCP is supplying war supplies such as gunpowder, artillery, and weapons subcomponents to Russia. When Zelinskiy announced on 9 April that the Ukrainian Army had captured two Chinese nationals fighting with Russians on the front line with details

On a quiet lane in Taipei’s central Daan District (大安), an otherwise unremarkable high-rise is marked by a police guard and a tawdry A4 printout from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs indicating an “embassy area.” Keen observers would see the emblem of the Holy See, one of Taiwan’s 12 so-called “diplomatic allies.” Unlike Taipei’s other embassies and quasi-consulates, no national flag flies there, nor is there a plaque indicating what country’s embassy this is. Visitors hoping to sign a condolence book for the late Pope Francis would instead have to visit the Italian Trade Office, adjacent to Taipei 101. The death of

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), joined by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), held a protest on Saturday on Ketagalan Boulevard in Taipei. They were essentially standing for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which is anxious about the mass recall campaign against KMT legislators. President William Lai (賴清德) said that if the opposition parties truly wanted to fight dictatorship, they should do so in Tiananmen Square — and at the very least, refrain from groveling to Chinese officials during their visits to China, alluding to meetings between KMT members and Chinese authorities. Now that China has been defined as a foreign hostile force,

On April 19, former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) gave a public speech, his first in about 17 years. During the address at the Ketagalan Institute in Taipei, Chen’s words were vague and his tone was sour. He said that democracy should not be used as an echo chamber for a single politician, that people must be tolerant of other views, that the president should not act as a dictator and that the judiciary should not get involved in politics. He then went on to say that others with different opinions should not be criticized as “XX fellow travelers,” in reference to