Some radical friends didn't share the enthusiastic reception for Lives of Others, the haunting recent film about life under the Stasi, the East German secret police.

It wasn't the acting or even the Big-Brother plot of hidden manipulation and control that they objected to -- what got up their noses was the complacent implicit assumption that the West wasn't an equally enthusiastic user of similar surveillance techniques, even if mostly (so far as we know) for commercial rather than political ends.

They have a point.

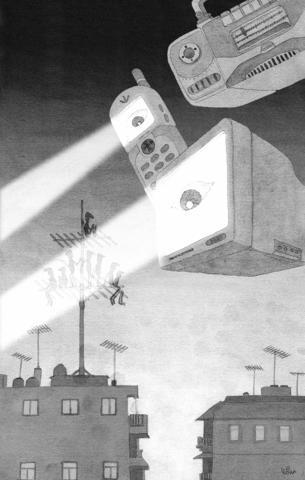

"We live in a surveillance society," was the bald assessment of a report for the UK's information commissioner last year that catalogued in detail the technologies and processes by which Britons are logged, profiled and digitized daily at work and at play through credit, loyalty, travel and swipe cards, mobile phones, congestion charges, work log-ins and activity monitors, interactions with public and private-sector call centers, not to mention the ubiquitous CCTV cameras.

One striking measure of the burgeoning of surveillance is the growth of the industry that provides it -- in the three years to last year the top 100 US surveillance companies had doubled in value to US$400 billion. Surveillance is big business.

Even individual surveillance uses are hard to track and regulate, as technology runs ahead of the ability to foresee its implications. But in combination with "function creep" -- where a mechanism set up for one purpose, like a public transport swipe card, is then used for another, such as tracking movement -- increasingly complex networks of information-sharing across private and public sectors, from credit-rating to benefits agencies and hospitals, make it almost impossible for people to assert their right to know the information held about them.

It's like a "first life" version of the virtual-reality Web site SecondLife.com -- whether we like it or not we all have shadowy "avatars," digital doubles of ourselves, assembled by computer from dozens of different database components and logged and managed in ways of which we are only dimly aware.

Although untethered from the office by mobiles and laptops, some remote workers find their digital selves more controlled and monitored than before. For consumers and citizens, racial and postcode profiling and credit rating are just the beginning. When you contact some call centers you are categorized by level of spending and served accordingly -- Amazon.com can price goods differently for different customers.

Not all surveillance is bad -- accurate records can protect the innocent as well as identify wrongdoers -- and some of it, as the information commissioner said, is an inescapable part of modern life.

The technology itself is neutral, as Lives of Others demonstrates, but the use that authorities make of it is the problem.

The report warns that it is naive and dangerous to sleepwalk into a world where gathering, processing and sorting personal data is no longer just an overlay, like CCTV cameras, but a part of life's basic infrastructure, without debate or understanding what it means.

Part of the danger is cock-up rather than conspiracy -- at a very basic level so much of the information gathered is just wrong. One study found that 22 percent of a sample of entries into a UK police computer contained errors, even when double-checked. Names are misspelled and addresses wrongly coded. The impact of such errors is compounded by sharing. What's more, the errors are not remedied by the enthusiastic addition of more technology -- a managerialist solution that often makes the original problem still harder to unravel, as well as locking us in to technology and expertise beyond democratic control.

At the same time, to a computer your digital identity is more real than the physical one; indeed, if you don't have a computer identity, you don't exist at all. Hence the phenomenon of the invisible consumer and the unreachable company, separated by the impenetrable barrier of the computer.

When, as is the way of technological advance, the monitoring of information is taken away from humans in the name of rationality and given over to algorithms, the wrongness can become surreal. If computers decide who gets passports or is employed, we really are rattling the bars of sociologist Max Weber's bureaucratic "iron cage."

Surveillance is a substitute for trust. At work or as citizens, some people break trust, so surveillance is necessary. The dilemma is that by fostering suspicion and making people feel mistrusted, it increases the chances that they act in ways that seem to justify the surveillance. Lives of Others plays on this tension, before ending on a note of wry individual redemption, a small victory for humanity.

Yet in real life, the nightmare prospect of surveillance managing us rather than the opposite is apparent, and it will take more than fiction to reverse it.

There is much evidence that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is sending soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to support Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — and is learning lessons for a future war against Taiwan. Until now, the CCP has claimed that they have not sent PLA personnel to support Russian aggression. On 18 April, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelinskiy announced that the CCP is supplying war supplies such as gunpowder, artillery, and weapons subcomponents to Russia. When Zelinskiy announced on 9 April that the Ukrainian Army had captured two Chinese nationals fighting with Russians on the front line with details

On a quiet lane in Taipei’s central Daan District (大安), an otherwise unremarkable high-rise is marked by a police guard and a tawdry A4 printout from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs indicating an “embassy area.” Keen observers would see the emblem of the Holy See, one of Taiwan’s 12 so-called “diplomatic allies.” Unlike Taipei’s other embassies and quasi-consulates, no national flag flies there, nor is there a plaque indicating what country’s embassy this is. Visitors hoping to sign a condolence book for the late Pope Francis would instead have to visit the Italian Trade Office, adjacent to Taipei 101. The death of

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), joined by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), held a protest on Saturday on Ketagalan Boulevard in Taipei. They were essentially standing for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which is anxious about the mass recall campaign against KMT legislators. President William Lai (賴清德) said that if the opposition parties truly wanted to fight dictatorship, they should do so in Tiananmen Square — and at the very least, refrain from groveling to Chinese officials during their visits to China, alluding to meetings between KMT members and Chinese authorities. Now that China has been defined as a foreign hostile force,

On April 19, former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) gave a public speech, his first in about 17 years. During the address at the Ketagalan Institute in Taipei, Chen’s words were vague and his tone was sour. He said that democracy should not be used as an echo chamber for a single politician, that people must be tolerant of other views, that the president should not act as a dictator and that the judiciary should not get involved in politics. He then went on to say that others with different opinions should not be criticized as “XX fellow travelers,” in reference to