It's a hot, sunny day on Goree Island, a short boat ride from Senegal's bustling capital, Dakar. In the cooling shade of an overhanging tree in the grounds of Mariama Ba school, Aminata Deme talked about a short film on slavery she and her classmates have just recorded. In it, the 14-year-old plays a girl who abuses her family's maid.

"I was one of the people mistreating the maid, which was bad. It was a very meaningful film and very interesting to make," Aminata said.

It's not uncommon in the more wealthy homes in Senegal's cities to have someone to help around the house. But the age of those performing the chores, the hours they work and the wages they receive have been called into question by the 19 pupils from Mariama Ba who shot the film, called My Maid, Not a Slave, as part of an anti-slavery project organized by the UK branch of the children's rights charity Plan International.

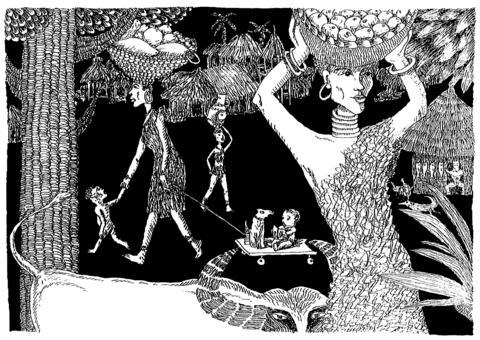

Over the past few months, the pupils at the girls' school, one of the most prestigious in Senegal, have been learning about the history of slavery, the impact the trade has had on west Africa and how new forms of the practice have been allowed to seep into society.

Organized by Plan UK and National Museums Liverpool to mark the bicentenary of the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade this year, the project, Make the Link, Break the Chain, involved schoolchildren from 13 schools based along the so-called slave triangle.

Pupils from Senegal, Sierra Leone, Brazil, Haiti and the UK created Web pages, produced written work and shared information online and by e-mail.

The youngsters then used video, music and art to interpret their findings. All their work will be showcased at the International Slavery Museum, which opens in Liverpool this week.

Goree is a fitting location for a project on slavery. Between 1776 and 1848 hundreds of thousands of slaves were shipped to the Americas from a transit house on the edge of the island. Walking around the house now, its bright red walls seem too cheerful for the horror of what went on there. Visitors are shown the shackles the slaves wore and the cramped rooms in which they lived.

It is a brutal reminder of the past, but as the work of Mariama Ba's pupils shows, a new form of slavery still exists in Senegal.

In a dusty village about 70km north of Dakar, 17-year-old Salimata Kandge talks about the two years she spent working as a maid in the capital. From the age of 13, she cooked and cleaned for 12 hours a day, seven days a week, for CFA15,000 a month -- about US$30 -- barely a dollar a day. She was verbally abused by her employers, ignored by people she met in the street and longed to go home.

"The bosses tell you that you are here for work and you have to work, and when you go out, there are other people who treat you like you are nothing," she said.

Absa Nguing, now 20, said when she was younger, she went to Dakar with her sisters and her mother, who needed to find work to feed the family. She never went to school and, at the age of 12, she too became a domestic maid.

"It was difficult when I became a maid, but I was obliged to do it," she said. "I worked with a woman who was blind. I went to the market one day and when I came back, the woman took the fish I bought and hit me with it. She was not happy with what I'd bought, but I didn't know because I was very young."

Two years ago, Salimata and Absa were brought back from Dakar to their home villages, thanks to an initiative supported by Plan International.

The organization has been involved in setting up training centers in needlework, hairdressing and metal work in villages around Thies, Senegal's second-largest city, to offer the youngsters vocational qualifications.

Salimata and Absa are now working towards diplomas in hairdressing and sewing respectively. Plan is also providing financial incentives to parents to keep their children at home and in school.

A combination of poverty and an education system that has little concern for those who struggle leads many young people to Dakar to search for work. According to UNICEF, 37 percent of children between the ages of five and 14 are involved in some form of work in Senegal.

Although primary and secondary education is compulsory -- and free -- many parents are still reluctant to send their children to school, and drop-out rates are high.

Children who finish their primary education have to sit an exam to determine if, and where, they will get a place in secondary school. Those who do well go to good schools, such as Mariama Ba, a state-funded institution that used to educate the daughters of the elite but now takes the brightest girls from across the country.

Those who perform poorly find their choices limited and often end up in classes of more than 80 children. Those who fail tend to disappear from the education radar altogether. If children make it through the first two years of secondary school, they sit a further exam to determine whether they will finish their education.

But some, mostly girls, do not get the chance to sit this exam. They are married off or are considered old enough to be sent out to earn money for the family, which in many cases for rural teenagers involves a perilous trip to the capital.

Salimata began working in Dakar after she finished primary school. She had failed her secondary exams, but even if she had passed, she might not have been allowed to stay on, as her family needed money.

"It's about poverty. Families need their children to go to work," said Falelou Seck, program unit manager at Plan in Thies.

Seck is charged with helping to bring children back from Dakar and prevent more going there. His work is concentrated in two regions around Thies that are home to more than 5,000 families. He estimates that at least one child from each family has been or is still working in Dakar. Many face physical and sexual abuse.

Parents are often ill-informed of the dangers their children face in the capital, or are so desperate for money they are willing to risk their child's welfare, Seck said.

His team has to convince parents of the benefits of keeping their children in their village, which means offering them education opportunities and a way to make money closer to home.

"We are reaching out to parents to explain the dangers and risks to their children, so that they will ask their children to come back," he said. "We try to stop them from leaving and keep them in school."

Teenagers who are keen to head to the bright lights of the city, imagining opportunity, rather than exploitation, are taken on trips to Dakar to see the reality. Those who still wish to go are given advice on how to stay safe.

"Every now and again, we do have children who make some success of themselves," Seck said. "We can't stop [them] from leaving, but we can prepare them and give them the skills, so they would not have to accept the worst kinds of work or conditions. We try to prepare them for their future."

The scheme is showing signs of success. Since it began in 2005, with a US$60,000 grant, some 320 children have returned from Dakar and at least 180 more have been tracked down and want to come back home.

There is much evidence that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is sending soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to support Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — and is learning lessons for a future war against Taiwan. Until now, the CCP has claimed that they have not sent PLA personnel to support Russian aggression. On 18 April, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelinskiy announced that the CCP is supplying war supplies such as gunpowder, artillery, and weapons subcomponents to Russia. When Zelinskiy announced on 9 April that the Ukrainian Army had captured two Chinese nationals fighting with Russians on the front line with details

On a quiet lane in Taipei’s central Daan District (大安), an otherwise unremarkable high-rise is marked by a police guard and a tawdry A4 printout from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs indicating an “embassy area.” Keen observers would see the emblem of the Holy See, one of Taiwan’s 12 so-called “diplomatic allies.” Unlike Taipei’s other embassies and quasi-consulates, no national flag flies there, nor is there a plaque indicating what country’s embassy this is. Visitors hoping to sign a condolence book for the late Pope Francis would instead have to visit the Italian Trade Office, adjacent to Taipei 101. The death of

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), joined by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), held a protest on Saturday on Ketagalan Boulevard in Taipei. They were essentially standing for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which is anxious about the mass recall campaign against KMT legislators. President William Lai (賴清德) said that if the opposition parties truly wanted to fight dictatorship, they should do so in Tiananmen Square — and at the very least, refrain from groveling to Chinese officials during their visits to China, alluding to meetings between KMT members and Chinese authorities. Now that China has been defined as a foreign hostile force,

On April 19, former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) gave a public speech, his first in about 17 years. During the address at the Ketagalan Institute in Taipei, Chen’s words were vague and his tone was sour. He said that democracy should not be used as an echo chamber for a single politician, that people must be tolerant of other views, that the president should not act as a dictator and that the judiciary should not get involved in politics. He then went on to say that others with different opinions should not be criticized as “XX fellow travelers,” in reference to