Tim Westergren never thought he'd run a dotcom startup. He was a musician, sleeping in tour vans on the road and recording the occasional film score.

When he did decide to start a business, he put six years of his life into it. This week, he is preparing to shut down his nascent UK operation and mulling the future of the US one, as legislators on both sides of the Atlantic threaten to kill his business.

Westergren founded Pandora, an online streaming music service based in California that lets people build personalized stations. A ruling by the US Copyright Royalty Board that technically came into force on July15 at least tripled the royalties that Pandora and other Internet radio companies pay.

The next day, the UK Copyright Tribunal unveiled its own royalty charges that made his business in the UK untenable and left other large Webcasters fuming.

Outraged appeals from the net radio industry failed to overturn the US ruling, which applies retrospectively from January last year. As of last week, Westergren and others are in hock to royalty collector SoundExchange for unpaid record label royalties. Under the ruling, the royalty rate will rise each year until 2010. But Pandora could be gone long before that.

"In the face of those rates, we can't carry on," Westergren said.

Music has two copyright holders.

The publisher or composer holds the rights to the lyrics and the melody, while the record label or performer holds the rights to the sound recording. Radio stations have historically paid royalties for the musical work to the publishers but not for performance rights.

This was a sore point for the labels, which finally won the right to charge for performance rights over Internet radio in 1998. The US government created a statutory license under which Webcasters would pay a set fee to the labels for performance rights. In 2002, the Small Webcasters Settlement Act created a haven of sorts for Webcasters with revenues of less than US$1.2 million -- who make up the bulk of the US' 30,000 Webcasters. This restricted royalties to 12 percent of their income -- even though terrestrial broadcasters with substantially greater revenues pay no performance royalties at all.

Nevertheless, Webcasters and the labels had reached an uneasy peace -- until the royalty board's ruling this March. That swept away the revenue-based royalty scheme for small Webcasters, forcing them to pay a per-song royalty like every-one else. Smaller Webcasters could find their royalty payments multiplying by up to 12 times, SaveNetRadio.org said.

The board also approved a minimum charge of US$500 per Internet radio station, which would be disastrous for those Webcasters who create personalized channels for each listener. Every time a user creates a channel in Pandora -- and many users have more than one -- Westergren would have to make another payment.

"Ninety percent of the Internet radio stations in the US will go out of business," warned David Van Dyke of analyst Bridge Ratings.

"Our goal is to continue to grow with Internet radio," says John Simson of Sound Exchange, which set up four years ago by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) to collect performance royalties. "We want to help our members to get value for the music being used."

But the labels benefit from Internet radio's promotional role, protests Kurt Hanson of Accu-Radio, a small Webcaster.

"Net radio is one of the few good things the record industry has going for it," he said. "It's giving airplay to thousands of artists that have never been able to get airplay before."

But something is bugging SoundExchange, and falling CD sales is probably it. CD sales fell 15 percent in the first half this year compared to the same time last year, according to Nielsen SoundScan, and that's an ongoing trend, Van Dyke said.

Falling CD sales are causing the labels to push for revenue from play services rather than product sales, suggests Bob Hamilton, who owns radio analyst New Radio Star. But he suspects that they were surprised when no one pushed back.

"SoundExchange bought in a proposal so high and ridiculous believing they'd have to negotiate," he said.

"I think they were shocked at what they got."

This might explain why Sound-Exchange offered three separate compromises to the industry in the weeks following the ruling. It extended the conditions of the Small Webcaster Settlement Act until 2010, in effect nixing the increased royalty payments for small Webcasters. Second, it offered to cap the per-station radio fee at US$2,500 per station. Last Thursday it increased that offer to a maximum of US$50,000 in per-station payments per Webcaster. That offer applies only if Webcasters work to avoid listeners recording music streams, which hints at the use of digital rights management technology.

But now the Webcasters want a better deal, and they're trying to renegotiate the Small Webcaster Settlement Act.

"It says that if you make more than US$1.2 million, your royalty payments go through the roof and you risk bankruptcy," said Jake Ward of SaveNetRadio.org.

Simson protests that most Webcasters are far below the US$1.2 million ceiling, and Ward admits that ad revenues are low. However, they are growing. Ad revenues for Internet radio grew by two-thirds to US$66 million in the US this year and will reach US$104 million next year, Bridge Ratings said.

Meanwhile, representatives are trying to push the Internet Radio Equality Act through Congress. This would fix performance-based royalties at 7.5 percent per year, which is more in line with what satellite radio providers like XM and Sirius pay.

If Webcasters lose their battle, the options are limited.

"We would move outside the US, probably," said Bill Goldsmith of small Webcaster Radio Paradise.

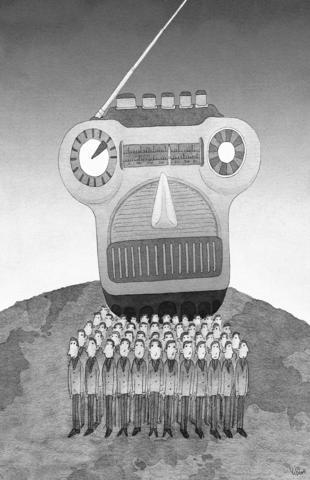

Another option is more ominous: Hanson believes that Webcasters might cut direct deals with the labels. The labels would offer cheaper licenses, he says, but those could come with a caveat: encroaching control of the stations' playlists.

Hamilton says that many of the larger Web stations have already cut deals with the labels, although because these deals are private there is no way of knowing what the terms are. In the UK, where performance licensing is more complex, direct deals are commonplace. UK-based Last.fm has signed deals with EMI, Warner and Sony BMG for access to their catalogs.

Internet radio didn't die on July 15 when the ruling came into effect. SoundExchange left the Small Webcaster's Settlement Act in place, so little will change for them as they thrash out the deal's terms. The 20 or so large Webcasters are technically expected to comply from this week, but Simson has left the door open for an ongoing discussion with them.

For the time being, companies like Pandora "aren't likely to be charged immediately," he said.

But the UK ruling, announced last Monday and effective from July 1, creates a new problem. In addition to a percentage of total revenue, for every track they play Webcasters will have to pay a minimum charge which is nine times higher than the US royalty board's projected per-track rate for 2010.

The terms were originally agreed last September, in a royalty settlement between record companies and parties including mobile phone operators, music download companies and the MCPS-PRS Alliance, which collects music royalties for publishers.

Three Webcasters -- AOL, Real Networks and Yahoo -- failed to settle.

Now, Webcasters face a war with regulators on both sides of the Atlantic.

Very large Webcasters may be able to stomach the fees, but Pandora is preparing to shut its service in the UK -- the only country served outside the US -- as early as this week, says international managing director Paul Brown.

The service, which had been offered informally while Pandora negotiated UK music licensing deals, was to formally launch by the end of the year, but it could never be profitable under the new rules, he said.

"We want to bring this good service to the UK, but it has to be on an economic base and if you're losing money for every hour then there's no business there," Brown lamented.

For Pandora UK at least, it turns out that July 16 really was the day the music died.

Chinese agents often target Taiwanese officials who are motivated by financial gain rather than ideology, while people who are found guilty of spying face lenient punishments in Taiwan, a researcher said on Tuesday. While the law says that foreign agents can be sentenced to death, people who are convicted of spying for Beijing often serve less than nine months in prison because Taiwan does not formally recognize China as a foreign nation, Institute for National Defense and Security Research fellow Su Tzu-yun (蘇紫雲) said. Many officials and military personnel sell information to China believing it to be of little value, unaware that

Before 1945, the most widely spoken language in Taiwan was Tai-gi (also known as Taiwanese, Taiwanese Hokkien or Hoklo). However, due to almost a century of language repression policies, many Taiwanese believe that Tai-gi is at risk of disappearing. To understand this crisis, I interviewed academics and activists about Taiwan’s history of language repression, the major challenges of revitalizing Tai-gi and their policy recommendations. Although Taiwanese were pressured to speak Japanese when Taiwan became a Japanese colony in 1895, most managed to keep their heritage languages alive in their homes. However, starting in 1949, when the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) enacted martial law

“Si ambulat loquitur tetrissitatque sicut anas, anas est” is, in customary international law, the three-part test of anatine ambulation, articulation and tetrissitation. And it is essential to Taiwan’s existence. Apocryphally, it can be traced as far back as Suetonius (蘇埃托尼烏斯) in late first-century Rome. Alas, Suetonius was only talking about ducks (anas). But this self-evident principle was codified as a four-part test at the Montevideo Convention in 1934, to which the United States is a party. Article One: “The state as a person of international law should possess the following qualifications: a) a permanent population; b) a defined territory; c) government;

The central bank and the US Department of the Treasury on Friday issued a joint statement that both sides agreed to avoid currency manipulation and the use of exchange rates to gain a competitive advantage, and would only intervene in foreign-exchange markets to combat excess volatility and disorderly movements. The central bank also agreed to disclose its foreign-exchange intervention amounts quarterly rather than every six months, starting from next month. It emphasized that the joint statement is unrelated to tariff negotiations between Taipei and Washington, and that the US never requested the appreciation of the New Taiwan dollar during the