Latin America, as the late Venezuelan author Carlos Rangel once wrote, has always had a "love-hate relationship" with the US. The love is expressed in its purest form: imitation. The hate -- more akin to resentment -- boils down to a frustrated desire to get Washington's attention.

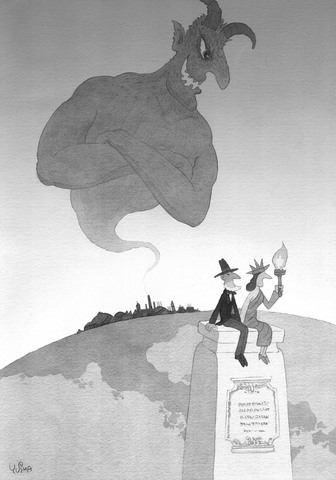

Cuba's Fidel Castro pulled it off in the 1960s, torturing the Kennedy brothers with his cigar and his Marxism; and now, in Venezuela, President Hugo Chavez is giving us a rerun. At least, this is the refrain of Nikolas Kozloff, a British-educated American who has written Hugo Chavez: Oil, Politics, and the Emerging Challenge to the United States.

Kozloff apparently believes that Americans have much to fear from Venezuela. His admiring study of Chavez, an up-by-the-bootstraps lieutenant colonel who tried and failed to take power in a coup and subsequently succeeded at the ballot box, is peppered with phrases like "in an alarming warning sign for George Bush," and, "in an ominous development for [US] policy makers."

Why does Kozloff think, as stated on the book jacket, that Venezuela represents a "potentially dangerous enemy to the [US]?" Caracas is the US' fourth-biggest oil exporter, so maybe some day, the implication is, it could cut us off.

And Chavez, with his friend you-know-who in Cuba, has taken to taunting the US and lobbying other Latin American countries against the brand of free-trade liberalism that Washington has advocated. Chavez has even been trying to form an energy alliance with Argentina and Brazil, for the ostensible purpose of using oil as a "weapon" against the gringos, and he has refused to permit US overflights in the war against cocaine.

Is this really worth getting all steamed up about? I lived in Venezuela during the 1970s, also a period of high oil prices and, not coincidentally, a time when the government was strutting its stuff as a regional (and vaguely anti-capitalist) power. Getting the US to worry -- or minimally to care -- was a high priority, as I realized when a friendly Venezuelan reporter eagerly asked me which of two left-wing political parties Americans "feared the most."

One of these parties was known by the acronym MIR and the other as MAS. The truth was that no Americans I knew had heard of either. My own relatives could barely distinguish Venezuela from Colombia or Peru. I didn't say that, of course. The local journalists were unfailingly kind to me, and I had no wish to hurt their feelings. I allowed, "I guess we fear each of them about the same." Anyway, in a few years, the price of oil collapsed, and the posturing from Caracas went with it.

Kozloff will perhaps appreciate the personal anecdote because his book is replete with them. He lets us in on his travels, Kerouac-style, so we are with him when he is hiking in the Andes, observing rural poverty, or acquainting himself with indigenous tribes.

Then the author is back in England, where he joins an "anti-capitalist May Day protest," at which one of his confreres defaces a statue of Winston Churchill. Then he is watching Chavez on TV, then protesting against globalism, then, in 2000, doing research for his dissertation in Caracas. He watches Al Gore and George Bush on the tube, cannot see much difference between them and casts his lot with Ralph Nader.

As for Chavez, the author portrays him, convincingly, as a soldier indignant about the moral flabbiness and corrupt ways of the career politicians he replaced. We learn that Chavez's antipathy toward American culture stems, in some measure, from his partly Indian blood lines. So it is that Chavez, a phrase maker to be sure, has rechristened Columbus Day "Indigenous Resistance Day." Resistance to what? He is no fan of liberal economics, free trade, cross-border investment, the prescriptions of the IMF nor, indeed, of capitalism itself.

This is all well and good with Kozloff. His analysis is essentially Marxist -- he sees trade as a one-way street that helps the rich and hurts the poor. His book is filled with the sort of new-lefty rhetoric I had thought went out in the 1970s. He applauds the Venezuelan president's idea for an alternative trade association -- meaning one not aligned with the US -- that, in Chavez's tedious phraseology, would be a "socially oriented trade bloc rather than one strictly based on the logic of deregulated profit maximization."

But neither Kozloff nor Chavez can escape the fact that the 1970s are over. Socialism hasn't worked; it's kaput. Free-market medicine (which Kozloff refers to by the more sinister-sounding "neo liberalism") hasn't always worked, but it's worked better than anything else.

And in fact, Kozloff's fantasy of a US threatened by left-wing Latinos is a vestige of a world that was dominated by a Moscow-Washington rivalry -- a world that no longer exists. The only way Venezuela could truly stop supplying the US with oil (which trades in a global market) would be to stop selling it to everyone, which isn't in the cards.

The right question to ask is not what the US has to fear from Chavez, but rather what Venezuelans have to fear from Chavez. The answer would seem to be plenty. He has militarized the government, emasculated the country's courts, intimidated the media, eroded confidence in the economy and hollowed out Venezuela's once-democratic institutions.

Chavez's rhetoric has provided a pleasing distraction to the country's poor, but it has not eradicated poverty. The real riddle of Venezuela today, as it was a generation ago, is why, despite its bountiful oil reserves, its fertile plains and its democratic traditions, it has been persistently unable to make an economic leap similar to that of Chile or of the various success stories in Asia. And writers who serve as cheerleaders for the failed idea of blaming the US are anything but Venezuela's friends.

Jan. 1 marks a decade since China repealed its one-child policy. Just 10 days before, Peng Peiyun (彭珮雲), who long oversaw the often-brutal enforcement of China’s family-planning rules, died at the age of 96, having never been held accountable for her actions. Obituaries praised Peng for being “reform-minded,” even though, in practice, she only perpetuated an utterly inhumane policy, whose consequences have barely begun to materialize. It was Vice Premier Chen Muhua (陳慕華) who first proposed the one-child policy in 1979, with the endorsement of China’s then-top leaders, Chen Yun (陳雲) and Deng Xiaoping (鄧小平), as a means of avoiding the

As the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) races toward its 2027 modernization goals, most analysts fixate on ship counts, missile ranges and artificial intelligence. Those metrics matter — but they obscure a deeper vulnerability. The true future of the PLA, and by extension Taiwan’s security, might hinge less on hardware than on whether the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) can preserve ideological loyalty inside its own armed forces. Iran’s 1979 revolution demonstrated how even a technologically advanced military can collapse when the social environment surrounding it shifts. That lesson has renewed relevance as fresh unrest shakes Iran today — and it should

In the US’ National Security Strategy (NSS) report released last month, US President Donald Trump offered his interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine. The “Trump Corollary,” presented on page 15, is a distinctly aggressive rebranding of the more than 200-year-old foreign policy position. Beyond reasserting the sovereignty of the western hemisphere against foreign intervention, the document centers on energy and strategic assets, and attempts to redraw the map of the geopolitical landscape more broadly. It is clear that Trump no longer sees the western hemisphere as a peaceful backyard, but rather as the frontier of a new Cold War. In particular,

The last foreign delegation Nicolas Maduro met before he went to bed Friday night (January 2) was led by China’s top Latin America diplomat. “I had a pleasant meeting with Qiu Xiaoqi (邱小琪), Special Envoy of President Xi Jinping (習近平),” Venezuela’s soon-to-be ex-president tweeted on Telegram, “and we reaffirmed our commitment to the strategic relationship that is progressing and strengthening in various areas for building a multipolar world of development and peace.” Judging by how minutely the Central Intelligence Agency was monitoring Maduro’s every move on Friday, President Trump himself was certainly aware of Maduro’s felicitations to his Chinese guest. Just