While we were opening the World Social Forum (Asia) with virtuoso performances of sufi music, the country's rulers were marking the centenary of the Muslim League -- the party that created Pakistan and has ever since been passed on from one bunch of rogues to another -- by gifting the organization to General Pervez Musharraf, the country's uniformed ruler.

The secular opposition leaders, Nawaz Sharif and Benazir Bhutto, are both in exile. If they returned home they would face arrest for corruption. Neither is in the mood for martyrdom or relinquishing control of their organizations. Meanwhile, the religious parties are happily implementing neoliberal policies in the North-West Frontier Province, which is under their control. Incapable of catering to the needs of the poor, they concentrate their fire on women and the godless liberals who defend them.

The military is so secure in its rule and the official politicians so useless that civil society is booming. Private television channels, like non-governmental organizations (NGOs), have mushroomed, and most views are permissible -- with the exception of frontal assaults on religion or the military. If civil society posed any real threat to the elite, the plaudits it receives would rapidly turn to menace.

It was thus no surprise that the WSF too had been permitted and facilitated by the local administration in Karachi. The WSF is now part of the globalized landscape and helps retrograde rulers feel modern. The event itself was no different from the others. Present were several thousand delegates, mainly from Pakistan but with a sprinkling from India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, South Korea and a few other countries.

Absent was any representation from China's burgeoning peasants' and workers' movements or its critical intelligentsia. Iran too was unrepresented, as was Malaysia. Israel's Jordanian enforcers who run the Amman regime harassed a Palestinian delegation, so only a handful managed to get through the checkpoints and reach Karachi. The huge earthquake in Pakistan last year disrupted plans. Otherwise, insist the organizers, the voices of Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo and Fallujah would have been heard.

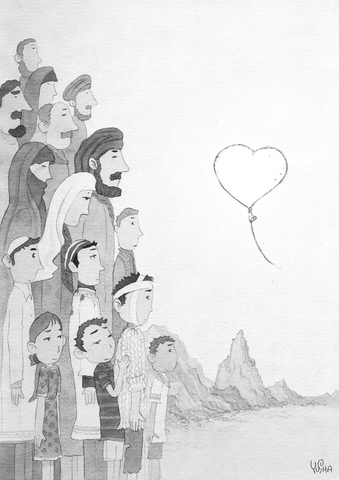

The fact that it happened at all in Pakistan was positive. People here are not used to hearing different voices and views. The WSF enabled many from repressed social groups and minority religions to make themselves heard: persecuted Christians from the Punjab, Hindus from Sind and women from everywhere told heart-rending stories of discrimination and oppression.

Present too was a sizeable class-struggle element: peasants fighting privatization of military farms in Okara; fisherfolk whose livelihoods are under threat, who complained about the Indus being diverted; workers from Baluchistan denouncing military brutality.

Teachers told how Pakistan's education system had almost ceased to exist. The common people who spoke were articulate, analytical and angry, in contrast to the stale rhetoric of Pakistan's political class. Much of what was said was broadcast on radio and television, with blanket coverage on the private networks.

What will the WSF leave behind? Very little, apart from goodwill. For the elite still dominates politics in the country. Small radical groups are doing their best, but there is no state-wide organization or movement that speaks for the dispossessed. The social situation is grim. The education system has collapsed and even lower-middle-class families can barely afford the fees of privatized schools. Small wonder that a poor family will send a male child to the madrasah, where he is fed, clothed and given a religious education.

Neoliberalism and religious fundamentalism are bedfellows.

The NGOs are no substitute for genuine social and political movements. In Africa, Palestine and elsewhere, NGOs have swallowed the neoliberal status quo. They operate like charities, trying to alleviate the worst excesses, but rarely question the systemic basis of the fact that 5 billion citizens of our globe live in poverty.

They may be NGOs in Pakistan, but on the global scale they are Western governmental organizations (WGOs), their cash flow conditioned by enforced agendas: former US secretary of state Colin Powell once referred to them as "our fifth column."

A few of them are doing good work, but the overall effect of NGO-ization has been to atomize the tiny layer of progressives and liberals in the country. Most of these men and women struggle for their individual NGOs to keep the money coming. Petty rivalries assume exaggerated proportions; politics in the sense of grassroots organization becomes virtually nonexistent. The salaries, in most cases, elevate WGO executives to the status of the local elites, creating the material basis for accepting the boundaries of the existing system.

The Latin American model emerging in the victories of Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez and Bolivian President Evo Morales has transcended the WGO world, but this is a far cry from Mumbai or Karachi, Jerusalem or Dar es Salaam.

Tariq Ali is the author of Clash of Fundamentalisms: Crusades, Jihads and Modernity.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has long been expansionist and contemptuous of international law. Under Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平), the CCP regime has become more despotic, coercive and punitive. As part of its strategy to annex Taiwan, Beijing has sought to erase the island democracy’s international identity by bribing countries to sever diplomatic ties with Taipei. One by one, China has peeled away Taiwan’s remaining diplomatic partners, leaving just 12 countries (mostly small developing states) and the Vatican recognizing Taiwan as a sovereign nation. Taiwan’s formal international space has shrunk dramatically. Yet even as Beijing has scored diplomatic successes, its overreach

After 37 US lawmakers wrote to express concern over legislators’ stalling of critical budgets, Legislative Speaker Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜) pledged to make the Executive Yuan’s proposed NT$1.25 trillion (US$39.7 billion) special defense budget a top priority for legislative review. On Tuesday, it was finally listed on the legislator’s plenary agenda for Friday next week. The special defense budget was proposed by President William Lai’s (賴清德) administration in November last year to enhance the nation’s defense capabilities against external threats from China. However, the legislature, dominated by the opposition Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), repeatedly blocked its review. The

In her article in Foreign Affairs, “A Perfect Storm for Taiwan in 2026?,” Yun Sun (孫韻), director of the China program at the Stimson Center in Washington, said that the US has grown indifferent to Taiwan, contending that, since it has long been the fear of US intervention — and the Chinese People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) inability to prevail against US forces — that has deterred China from using force against Taiwan, this perceived indifference from the US could lead China to conclude that a window of opportunity for a Taiwan invasion has opened this year. Most notably, she observes that

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) said on Monday that it would be announcing its mayoral nominees for New Taipei City, Yilan County and Chiayi City on March 11, after which it would begin talks with the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) to field joint opposition candidates. The KMT would likely support Deputy Taipei Mayor Lee Shu-chuan (李四川) as its candidate for New Taipei City. The TPP is fielding its chairman, Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌), for New Taipei City mayor, after Huang had officially announced his candidacy in December last year. Speaking in a radio program, Huang was asked whether he would join Lee’s