More than three decades after the US' Endangered Species Act gave the federal government tools and a mandate to protect animals, insects and plants threatened with extinction, the landmark law is facing the most intense efforts ever by White House officials, members of Congress, landowners and industry to limit its reach.

More than any time in the law's 32-year history, the obligations it imposes on government -- and, indirectly, on landowners -- are being challenged in the courts, reworked in the agencies responsible for enforcing it and re-examined in Congress.

In some cases, the challenges are broad and sweeping, as when the Bush administration, in a legal battle over the best way to protect endangered salmon, declared western dams to be as much a part of the landscape as the rivers they control. In others, the actions are deep in the realm of regulatory bureaucracy, as when a White House appointee at the Interior Department sought to influence scientific recommendations involving the sage grouse, a bird whose habitat includes areas of likely oil and gas deposits.

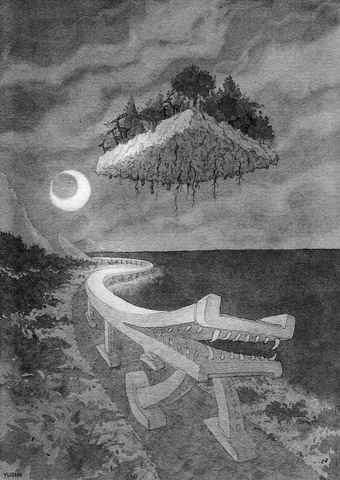

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

Some environmentalists readily concede that the law has long overemphasized the stick and has provided fewer carrots for private interests than it might. But some of them also fear that the law's defects will be used as a justification for a wholesale evisceration.

"There's an alignment of the planets of people against the Endangered Species Act in Congress, in the White House and in the agencies," said Jamie Rappaport Clark, executive vice president of Defenders of Wildlife, a lobbying group based in Washington.

On the opposite side, Robert Thornton, a lawyer for developers and Native American tribes in Southern California, has argued for years that the government goes too far to protect threatened species and curtails people's ability to use their own land.

"I've raised a child and sent him through college waiting for Congress to amend the Endangered Species Act," he said. "But I do think that a lot of forces are joining now."

The Endangered Species Act of 1973 set out a goal that, polls show, is still widely admired: ensuring that species facing extinction be saved and that robust populations be restored.

Currently 1,264 species are considered threatened or endangered. Some, like the bighorn sheep of the Southern California mountains, have obvious popular appeal and a constituency, while others, like the Kretschmarr Cave mold beetle in south Texas, are an acquired taste.

But in the past 30 years, lawsuits from all sides have proliferated. And more private land, particularly in the West, has been designated critical habitat for species, potentially subjecting it to federal controls that could limit construction, logging, fishing and other activities.

A "critical habitat" designation gives the federal government no direct authority to regulate private land use, but it does require federal agencies to take the issue into account when making regulatory decisions about private development.

The conflicts are becoming sharper as the needs of newly recognized endangered species are interfering more often with the demands of exurban development.

Western governors, who met in San Diego last year in a minisummit meeting on the act, are also weighing in with Congress, for the most part seeking to explore new means of species conservation while clarifying -- or limiting -- local and state government obligations under the law.

And Republican Representative Richard Pombo, chairman of the House Resources Committee, is preparing legislation that is likely to curb how much land or water can be defined as critical habitat.

Pombo, who attended the gathering in San Diego, said in an interview that there was some common ground on the critical-habitat issue. But, he added, consensus will be harder to find on proposals he is considering that would change how the agencies weigh available science.

Even without congressional rewriting, the federal agencies involved have taken a different attitude in the past four years, sometimes raising the bar of scientific proof and giving more weight than before to the economic impact of Endangered Species Act decisions.

In one instance, a top aide to Craig Manson, the assistant interior secretary who oversees the Fish and Wildlife Service, edited the scientific assessment of the sage grouse's status, playing down accounts of its range and population declines. The edited assessment and the original document prepared by scientists were sent to a panel of experts, which recommended against listing the grouse as endangered. The Interior Department did not list it.

In the case of the salmon, a US district judge in Portland, Oregon, last month rejected the Bush administration's interpretation of its obligation to endangered fish, including its argument that dams should be considered part of the landscape.

Noah Greenwald, a biologist with the Center for Biological Diversity, said that under President George W. Bush, the Interior Department has been much less aggressive than under former president Bill Clinton in putting species on the endangered list.

Under Clinton, he said, the Interior Department agreed to place a species on the list in 88 percent of the instances in which it made a decision. Under Bush, the figure is 52 percent, according to Greenwald's analysis of federal data.

The Bush administration has expanded on the Clinton administration's reluctance to delineate critical habitat. The administration includes a statement in all documents on the subject saying that the designation of critical habitat "provides little real conservation benefit, is driven by litigation rather than biology, forces designations to be made before complete scientific information is available" and "imposes huge social and economic costs."

Economic analyses, which the law allows for in decisions on territory, are now the leading reason for reducing the size of species' critical habitat, according to a report by the National Wildlife Federation.

In 2003, the report says, lands proposed as critical habitat by biologists were reduced by one-third; 69 percent of those reductions were based on economic factors, up from less than 1 percent in 2001. Territory can also be removed from proposed critical habitat if higher-ranking officials believe a species does not need it.

Manson, the assistant interior secretary, said in an interview that the interior secretary has the discretion to make such decisions, and that guidelines from the Office of Management and Budget are followed in performing economic analyses.

The National Wildlife Federation argues that the administration assigns little economic benefit to habitat designations, to which Manson responded: "The National Wildlife Federation and other groups have a different view of what ought to count as benefits. That's a legitimate policy difference."

Environmental groups argue that the land-use provisions of the law have been working, because federal data shows that 68 percent of listed species whose statuses are known have stable or recovering populations.

Even so, some environmentalists indicate gingerly that some of their number may have overreached or, more precisely, over-sued.

"Litigation is a hammer, but not every problem is a nail," said Michael Bean, a co-director of the Center for Conservation Incentives at Environmental Defense.

"The good news about litigation has been that it has forced the government to take seriously its obligations," he said.

Environmentalists have had considerable success in the courts, most memorably in 1978, when the Supreme Court blocked -- temporarily -- construction of the Tellico Dam in Tennessee to preserve a tiny fish, the snail darter.

This month, the Supreme Court refused to hear a case challenging enforcement of the law, in a dispute involving six endangered species of small insects that live in caves in Texas, including the Kretschmarr Cave mold beetle. Developers said the property would be worth US$60 million if development were not limited by the Endangered Species Act.

And in the desert around Palm Springs, California, the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians is suing the government because more than half of the tribe's 12,500 hectares fall into an area the Fish and Wildlife Service says is critical to the conservation of the endangered bighorn sheep. The sheep's numbers in the area were down to about 280 when they were listed as endangered in 1998. A recent count put the number above 700.

The tribe says the designation creates "an economic impact of hundreds of millions of dollars" by complicating plans to develop resort condominiums and a golf course near tribal land.

There have been compromises on habitats. In hundreds of areas, various groups with an interest have cooperated on "habitat conservation plans" to help species on the brink.

Such plans, like one around Tucson, Arizona, regarding the endangered pygmy owl, have been promoted by both the Clinton and Bush administrations.

But the plans do not tend to flourish where litigation is rife.

Steven Quarles, an industry lawyer with the Washington firm of Crowell and Moring, said that until there was a legislative compromise that Senate moderates could support, "what we'll see is a chipping away at the act by federal rules and guidances from the executive branch, and litigation from both sides."

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has long been expansionist and contemptuous of international law. Under Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平), the CCP regime has become more despotic, coercive and punitive. As part of its strategy to annex Taiwan, Beijing has sought to erase the island democracy’s international identity by bribing countries to sever diplomatic ties with Taipei. One by one, China has peeled away Taiwan’s remaining diplomatic partners, leaving just 12 countries (mostly small developing states) and the Vatican recognizing Taiwan as a sovereign nation. Taiwan’s formal international space has shrunk dramatically. Yet even as Beijing has scored diplomatic successes, its overreach

In her article in Foreign Affairs, “A Perfect Storm for Taiwan in 2026?,” Yun Sun (孫韻), director of the China program at the Stimson Center in Washington, said that the US has grown indifferent to Taiwan, contending that, since it has long been the fear of US intervention — and the Chinese People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) inability to prevail against US forces — that has deterred China from using force against Taiwan, this perceived indifference from the US could lead China to conclude that a window of opportunity for a Taiwan invasion has opened this year. Most notably, she observes that

For Taiwan, the ongoing US and Israeli strikes on Iranian targets are a warning signal: When a major power stretches the boundaries of self-defense, smaller states feel the tremors first. Taiwan’s security rests on two pillars: US deterrence and the credibility of international law. The first deters coercion from China. The second legitimizes Taiwan’s place in the international community. One is material. The other is moral. Both are indispensable. Under the UN Charter, force is lawful only in response to an armed attack or with UN Security Council authorization. Even pre-emptive self-defense — long debated — requires a demonstrably imminent

Since being re-elected, US President Donald Trump has consistently taken concrete action to counter China and to safeguard the interests of the US and other democratic nations. The attacks on Iran, the earlier capture of deposed of Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro and efforts to remove Chinese influence from the Panama Canal all demonstrate that, as tensions with Beijing intensify, Washington has adopted a hardline stance aimed at weakening its power. Iran and Venezuela are important allies and major oil suppliers of China, and the US has effectively decapitated both. The US has continuously strengthened its military presence in the Philippines. Japanese Prime