Recent news coverage showed Ken Lay, the former chief executive officer (CEO) of Enron, being led away in handcuffs. Finally -- years after Enron's collapse -- Lay faces charges for what happened when he was at the helm. As is so often the case in such circumstances, the CEO pleads innocence: he knew nothing about what his underlings were doing. Bosses like Lay always seem to feel fully responsible for their companies' successes -- how else could they justify their exorbitant compensation? But the blame for failure -- whether commercial or criminal -- always seems to lie elsewhere.

America's courts (like Italy's courts in the case of Parmalat) will make the final judgment over criminal and civil liability under existing law. But there is a broader issue at stake in such cases: to what extent should a CEO be held responsible for what happens under his watch?

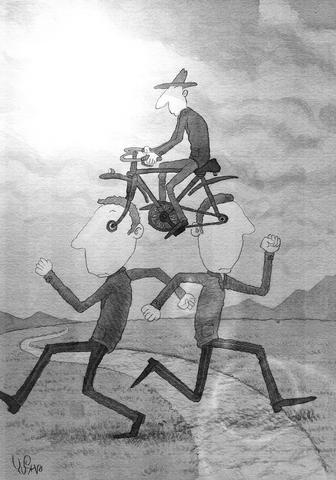

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

Clearly, no CEO of a large corporation, with hundreds of thousands of employees, can know everything that goes on inside the company he or she runs. But if the CEO is not accountable, who is? Those below him claim that they were just doing what they thought was expected of them. If they were not following precise orders, they were at least responding to vague pro forma instructions from the top: don't do anything illegal, just maximize profits. The result, often enough, is a climate within which managers begin to feel that it is acceptable to skirt the edges of the law or to fudge company accounts.

Even though a CEO cannot know everything, he or she is still ultimately responsible for what occurs in the company they run. They choose their subordinates, so it is their responsibility to ask the hard questions about what is going on under their watch. More importantly, it is their responsibility to create a climate that encourages, or discourages, certain kinds of activities. Simply put, it is their responsibility to be true leaders.

What's true for business bosses is doubly true for presidents and prime ministers. The US is in the process of choosing who will lead it for the next four years. President George W. Bush may claim that he didn't know that the information he was provided by the CIA concerning weapons of mass destruction in pre-war Iraq was so faulty. He may also claim that, with many thousands of troops under his command, it was impossible for him to ensure that US soldiers were not committing atrocities, torture, or violations of civil liberties.

But there is a fundamental sense in which Bush, like Lay, is culpable, and must be held accountable. Just as a CEO with a record not only of poor performance, but also of massive corporate misconduct, should be fired, so, too, should political leaders be held to a similar standard. Bush had a responsibility for the behavior of the people working for him. Instead, almost across the board in his administration, he chose as advisors people akin to Lay.

Bush chose as his vice-president a man who once served as CEO of Halliburton. Dick Cheney clearly cannot be held responsible for corporate misconduct after he left Halliburton, but there is mounting evidence about misconduct that took place while he was at the helm. Similarly, at the Securities and Exchange Commission, Bush appointed in the person of Harvey Pitt a fox to guard the chickens -- until public outrage forced Pitt's resignation.

Bush chose the people who provided him with faulty information about Iraq, or at least he chose the heads of the organizations that provided the faulty information. He chose his defense secretary and attorney general. He, and the people he appointed, created an environment of secrecy, a system in which the normal checks on the accuracy of information were removed.

Most importantly, Bush did not ask the hard questions -- perhaps because he, like those below him, already knew the answers they wanted. They created a closed culture, impervious to contradictory facts, a culture in which civil rights have been given short shrift and some people have been deemed not to deserve any rights at all.

Only such a culture -- one that undermined the longstanding presumption that an accused person is innocent until proven guilty -- could produce the Bush administration's niggling legal distinctions concerning what is and what is not torture. The abuses that have been documented at places such as Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo may not have been an inevitable consequence of the administration's legal memos, but surely those memos increased enormously the likelihood that torture would be viewed as acceptable.

Many Americans will reject Bush this November because of the poor performance of the economy or the quagmire in Iraq. Others will oppose him due to his environmental record or his budget priorities. But the intensity of opposition in America to Bush runs deeper than any single issue. There is a growing recognition that the values he and his administration reflect are the antithesis of what America has long stood for -- the values of an open society, in which differences of view are freely debated within a culture of civility and mutual respect for the rights of all.

The battle being waged in America today to restore these values is one that has been waged repeatedly around the world. Both in America and elsewhere, much hinges on the outcome, for it is nothing less than a battle to force our leaders to accept responsibility for their actions.

Joseph Stiglitz is professor of economics at Columbia University and a member of the Commission on the Social Dimensions of Globalization. He received the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2001. Copyright: Project Syndicate

Donald Trump’s return to the White House has offered Taiwan a paradoxical mix of reassurance and risk. Trump’s visceral hostility toward China could reinforce deterrence in the Taiwan Strait. Yet his disdain for alliances and penchant for transactional bargaining threaten to erode what Taiwan needs most: a reliable US commitment. Taiwan’s security depends less on US power than on US reliability, but Trump is undermining the latter. Deterrence without credibility is a hollow shield. Trump’s China policy in his second term has oscillated wildly between confrontation and conciliation. One day, he threatens Beijing with “massive” tariffs and calls China America’s “greatest geopolitical

Ahead of US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping’s (習近平) meeting today on the sidelines of the APEC summit in South Korea, an op-ed published in Time magazine last week maliciously called President William Lai (賴清德) a “reckless leader,” stirring skepticism in Taiwan about the US and fueling unease over the Trump-Xi talks. In line with his frequent criticism of the democratically elected ruling Democratic Progressive Party — which has stood up to China’s hostile military maneuvers and rejected Beijing’s “one country, two systems” framework — Lyle Goldstein, Asia engagement director at the US think tank Defense Priorities, called

A large majority of Taiwanese favor strengthening national defense and oppose unification with China, according to the results of a survey by the Mainland Affairs Council (MAC). In the poll, 81.8 percent of respondents disagreed with Beijing’s claim that “there is only one China and Taiwan is part of China,” MAC Deputy Minister Liang Wen-chieh (梁文傑) told a news conference on Thursday last week, adding that about 75 percent supported the creation of a “T-Dome” air defense system. President William Lai (賴清德) referred to such a system in his Double Ten National Day address, saying it would integrate air defenses into a

The central bank has launched a redesign of the New Taiwan dollar banknotes, prompting questions from Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators — “Are we not promoting digital payments? Why spend NT$5 billion on a redesign?” Many assume that cash will disappear in the digital age, but they forget that it represents the ultimate trust in the system. Banknotes do not become obsolete, they do not crash, they cannot be frozen and they leave no record of transactions. They remain the cleanest means of exchange in a free society. In a fully digitized world, every purchase, donation and action leaves behind data.