What, precisely, is so bad about sex between adult siblings, bestiality, and the eating of corpses? Most people insist such acts are morally wrong, but when psychologists ask why, the answers make little sense. For instance, people often say incestuous sex is immoral because it runs the risk of begetting a deformed child, but if this was their real reason, they should be happy if the siblings were to use birth control -- and most people are not. One finds what the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt called "moral dumbfounding," a gut feeling that something is wrong combined with an inability to explain why.

Haidt suggests we are dumbfounded because, despite what we might say to others and perhaps believe ourselves, our moral responses are not based on reason. They are instead rooted in revulsion: incest, bestiality and cannibalism disgust us, and our disgust gives rise to moral outrage.

Some see disgust as a reliable moral guide. Leon Kass, chairman of the US president's commission on bioethics, wrote an article in 1997 called "The Wisdom of Repugnance," in which he concedes that this revulsion is "not an argument," but then goes on to argue: "In some crucial cases, however, it is the emotional expression of deep wisdom, beyond wisdom's power completely to articulate it."

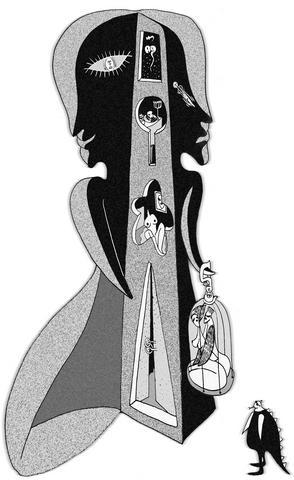

ILLUSTRATION MOUNTAIN PEOPLE

This conclusion has practical implications: Kass argues that the idea of human cloning is disgusting, and he sees this as good reason to ban it. Some from both sides of the political spectrum would agree.

Disgust has humble origins. At root, it is a biological adaptation, warding us away from ingesting certain substances that could make us sick. This is why feces, vomit, urine and rotten meat are universally disgusting; they contain harmful toxins. We react strongly to the idea of touching such substances and find the notion of eating them worse. This Darwinian perspective also explains why we see disgusting substances as contaminants -- if some food makes even the slightest contact with rotting meat, for instance, it is no longer fit to eat. After all, the micro-organisms that can harm us spread by contact, and so you should not only avoid disgusting things, you should avoid anything that the disgusting things make contact with. For these reasons, the psychologist Steven Pinker has described disgust as "intuitive microbiology."

So some of our disgust is hard-wired. This does not mean babies experience disgust. They are immobile and it would be a cruel trick of evolution to have them lie in perpetual self-loathing, unable to escape their revolting bodily wastes. But when disgust first emerges in young children, it is a consequence of brain maturation, not early experience or cultural teaching.

Children are prepared to do some learning, because while some things are universally dangerous, others vary according to the environment. This is particularly the case for animal flesh, and so in the first few years of life, children monitor what adults around them eat and establish the boundaries of acceptable (and hence non-disgusting) foods. By the time one is an adult the disgust reactions are fairly locked in, and it is difficult for most adults to try new foods, particularly new meats. (Most readers of this piece, for instance, would be queasy at the idea of eating grubs, cockroaches or dogs.)

If disgust were limited to food, it would have little social relevance. But, as a perverse evolutionary accident, this emotion that evolved for our protection has turned on us -- we can be disgusted by ourselves and others.

The history of disgust is an ugly one. The philosopher Martha Nussbaum, who is the main critic of a disgust-based morality, observes that "throughout history, certain disgust properties -- sliminess, bad smell, stickiness, decay, foulness -- have repeatedly and monotonously been associated with Jews, women, homosexuals, untouchables, lower-class people -- all of those are imagined as tainted by the dirt of the body."

The Nazis evoked disgust by depicting Jews as vermin, as unclean and as engaging in filthy acts. Male homosexuals are an easy target here; Nussbaum points out that when she was involved in a trial concerning gay rights in Colorado, opponents of gay rights testified that gay men drank blood and ate feces.

Disgust is not entirely sordid. It can be used as well to motivate a spiritual existence, by eliciting a negative reaction to our material bodies. St. Augustine, for instance, was influenced by Cicero's vivid image of the Etruscan pirate's torture of prisoners by strapping a corpse to them, face to face. This, Augustine maintained, is the fate of the soul, chained to a physical body as one would be chained to a rotting corpse.

You cannot talk someone out of disgust. But it can be defeated by other emotions. After comedian Stephen Fry outlines what he sees as the disgusting nature of sexual intimacy -- "I would be greatly in the debt of the man who could tell me what would ever be appealing about those damp, dark, foul-smelling and revoltingly tufted areas of the body that constitute the main dishes in the banquet of love" -- he notes that sexual arousal can override our civilized reticence: "Once under the influence of the drugs supplied by one's own body, there is no limit to the indignities, indecencies, and bestialities to which the most usually rational and graceful of us will sink."

Love can have a similar effect -- consider a parent changing a child's diaper, or the Catholic depictions of saints cleaning the wounds of lepers.

Disgust can also fade as it begins, through association and imagery, through positive depictions of once-reviled objects. In the 1960s, most Americans and Europeans disapproved of interracial marriage, and revulsion at such couplings played no small role. This has changed considerably, as has the reaction to homosexual relationships. It is not abstract argument driving this change in cultural values; it is Queer Eye for the Straight Guy.

The irrationality of disgust suggests it is unreliable as a source of moral insight. There may be good arguments against gay marriage, partial-birth abortions and human cloning, but the fact that some people find such acts to be disgusting should carry no weight.

Does this conclusion go too far? Commenting on the sadistic abuse of Iraqi prisoners, US President George W. Bush expressed "deep disgust" and said the images made him sick to his stomach.

This common reaction seems to be the right one; disgust is more apt than anger or dismay or even shame. In fact, disgust plays a double role here. Not only are the images of torture disgusting to those who view them -- and their sexual nature plays no small role in this regard -- but also part of the torture inflicted on the prisoners was their forced participation in acts they found revolting.

Wouldn't the staunchest critic of disgust agree that here at least this emotion does tell us something about right and wrong?

Not necessarily.

What was wrong about Abu Ghraib had to do with the suffering of the prisoners and the sadism of those who caused this suffering. It would have been just as wrong if there were no visual record. It also would have been worse if the prisoners had been shot dead. But news of simple murder does not usually prompt disgust, and would never have led to the same sort of moral outrage.

Even in these casese, we are better off without the distraction of disgust.

Paul Bloom is a psychology professor at Yale University and author of Descartes' Baby: How Child Development Explains What Makes Us Human.

In 2009, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) made a welcome move to offer in-house contracts to all outsourced employees. It was a step forward for labor relations and the enterprise facing long-standing issues around outsourcing. TSMC founder Morris Chang (張忠謀) once said: “Anything that goes against basic values and principles must be reformed regardless of the cost — on this, there can be no compromise.” The quote is a testament to a core belief of the company’s culture: Injustices must be faced head-on and set right. If TSMC can be clear on its convictions, then should the Ministry of Education

This should be the year in which the democracies, especially those in East Asia, lose their fear of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) “one China principle” plus its nuclear “Cognitive Warfare” coercion strategies, all designed to achieve hegemony without fighting. For 2025, stoking regional and global fear was a major goal for the CCP and its People’s Liberation Army (PLA), following on Mao Zedong’s (毛澤東) Little Red Book admonition, “We must be ruthless to our enemies; we must overpower and annihilate them.” But on Dec. 17, 2025, the Trump Administration demonstrated direct defiance of CCP terror with its record US$11.1 billion arms

The Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) provided several reasons for military drills it conducted in five zones around Taiwan on Monday and yesterday. The first was as a warning to “Taiwanese independence forces” to cease and desist. This is a consistent line from the Chinese authorities. The second was that the drills were aimed at “deterrence” of outside military intervention. Monday’s announcement of the drills was the first time that Beijing has publicly used the second reason for conducting such drills. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership is clearly rattled by “external forces” apparently consolidating around an intention to intervene. The targets of

China’s recent aggressive military posture around Taiwan simply reflects the truth that China is a millennium behind, as Kobe City Councilor Norihiro Uehata has commented. While democratic countries work for peace, prosperity and progress, authoritarian countries such as Russia and China only care about territorial expansion, superpower status and world dominance, while their people suffer. Two millennia ago, the ancient Chinese philosopher Mencius (孟子) would have advised Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) that “people are the most important, state is lesser, and the ruler is the least important.” In fact, the reverse order is causing the great depression in China right now,