When Japanese soldiers arrive in Iraq later this month, they won't be making war. They will be making history.

The dispatch, expected to become Japan's biggest and riskiest overseas military mission since World War II, marks a milestone in a shift away from a purely defensive posture toward a larger international role for the nation's military.

Japanese troops in Iraq will operate in what experts agree is a conflict zone, where the risk of casualties is high and the blue helmets of a UN peacekeeping force are nowhere to be seen.

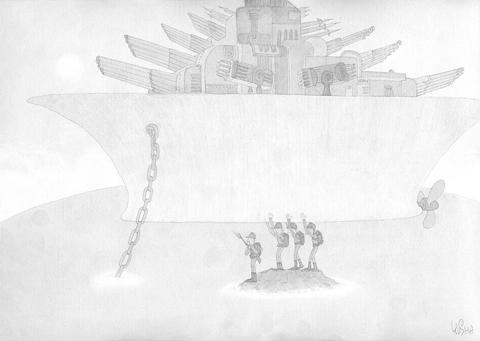

YUSHA

"Is Japan's security policy undergoing a major transformation? I think the answer is `yes,'" said Richard Samuels, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor.

"Putting `boots on the ground' in Iraq is fundamentally different from anything they have done in the past half century."

If successful, the Iraqi operation could become a model for future missions and accelerate a drive by neo-conservatives in Japan to revise its pacifist Constitution.

No member of Japan's military has fired a shot in combat or been killed in an overseas mission since World War II, and substantial casualties in Iraq could spark a public backlash that would rock Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi's government and hamper the forging of a new security policy.

"There might be a setback because of severe casualties," said Akio Watanabe, president of the Research Institute for Peace and Security, a think tank. "Public opinion is still very fluid in that sense."

A small advance army team is expected to leave later this week for southern Iraq, where they will act as scouts for a Japanese force that could number some 1,000 personnel on a mission to provide humanitarian aid and help rebuild the country.

A law enabling the dispatch limits its activities to "non-combat" zones, a concept hard to apply in Iraq, where at least 261 US and allied military personnel have been killed in attacks since May, when US President George W. Bush declared major combat over.

Japan's constitution renounces the right to wage war, bans the maintenance of a military except for defensive purposes, and has been interpreted as prohibiting the exercise of the right of collective self-defense, or aiding allies when they are attacked.

Untested in combat

The Self-Defense Forces (SDF), as the military is known, celebrate their 50th birthday this year, and though untested in combat are comparable in terms of spending and manpower to those of Britain.

For most of those 50 years, the forces were kept at home and efforts to expand their reach and role constrained by the Constitution as well as by reluctance to fan fears among Asian neighbors of resurgent Japanese militarism.

But stung by criticism of a "checkbook diplomacy" which gave cash but no troops for the 1991 Gulf War, Japan has stretched the limits of the Constitution over the past dozen years.

A 1992 law allowed Japanese forces to take part in UN-led peacekeeping operations, though with severe restrictions.

In 2001, Japan deployed its navy to the Indian Ocean to provide logistical support for the US-led war in Afghanistan, the first post-World War II dispatch to a war situation.

Experts agree, though, that the level of risk and absence of a clear UN mandate make the Iraq operation qualitatively different.

HUGGING AMERICA

Behind Koizumi's decision to take such a risky step is both a long-felt desire to normalize Japan's gun-shy, postwar defense policies and more recent worries about North Korea's nuclear and missile programs and China as an emerging regional power.

The US, Tokyo's main security ally, has also been pressuring Japan to take a bigger global role.

"If they didn't fear the possibility of abandonment by the United States on North Korea, they wouldn't feel the need to hug the United States more vigorously," Samuels said.

Koizumi backed the US-led war on Iraq despite opposition from the majority of Japanese voters and is moving ahead on the troop dispatch to Iraq in the face of polls showing that most of the public want to wait at least until the country is safer.

While many voters appear to be abandoning the pacifism that defined Japan's postwar security debate, a sense of forced obedience to Washington has fostered some resentment.

"The feeling is mixed. We love America, but we don't like our people always having to obey US pressure," said defense policy expert Satoshi Morimoto.

Few, however, would suggest that Japan try to go it alone on defense in the foreseeable future.

Despite the policy shift, few expect Japan to soon become a "Britain of Asia," fighting alongside US forces overseas.

"The Japanese government cannot be so bold," Watanabe said.

"I think they will stick to providing logistical support rather than actual fighting. My conclusion as to whether Japan has crossed the Rubicon [taken an irrevocable step] is `yes,' but very cautiously."

The conflict in the Middle East has been disrupting financial markets, raising concerns about rising inflationary pressures and global economic growth. One market that some investors are particularly worried about has not been heavily covered in the news: the private credit market. Even before the joint US-Israeli attacks on Iran on Feb. 28, global capital markets had faced growing structural pressure — the deteriorating funding conditions in the private credit market. The private credit market is where companies borrow funds directly from nonbank financial institutions such as asset management companies, insurance companies and private lending platforms. Its popularity has risen since

The Donald Trump administration’s approach to China broadly, and to cross-Strait relations in particular, remains a conundrum. The 2025 US National Security Strategy prioritized the defense of Taiwan in a way that surprised some observers of the Trump administration: “Deterring a conflict over Taiwan, ideally by preserving military overmatch, is a priority.” Two months later, Taiwan went entirely unmentioned in the US National Defense Strategy, as did military overmatch vis-a-vis China, giving renewed cause for concern. How to interpret these varying statements remains an open question. In both documents, the Indo-Pacific is listed as a second priority behind homeland defense and

Every analyst watching Iran’s succession crisis is asking who would replace supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Yet, the real question is whether China has learned enough from the Persian Gulf to survive a war over Taiwan. Beijing purchases roughly 90 percent of Iran’s exported crude — some 1.61 million barrels per day last year — and holds a US$400 billion, 25-year cooperation agreement binding it to Tehran’s stability. However, this is not simply the story of a patron protecting an investment. China has spent years engineering a sanctions-evasion architecture that was never really about Iran — it was about Taiwan. The

In an op-ed published in Foreign Affairs on Tuesday, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairwoman Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) said that Taiwan should not have to choose between aligning with Beijing or Washington, and advocated for cooperation with Beijing under the so-called “1992 consensus” as a form of “strategic ambiguity.” However, Cheng has either misunderstood the geopolitical reality and chosen appeasement, or is trying to fool an international audience with her doublespeak; nonetheless, it risks sending the wrong message to Taiwan’s democratic allies and partners. Cheng stressed that “Taiwan does not have to choose,” as while Beijing and Washington compete, Taiwan is strongest when